Stephen’s Sausage Roll (homepage, Steam $30, Humble $30 – Increpare gets the most money if you buy it here, plus you get a Steam key)

This is the beginning of a series of reviews of sublime games. The sublime is, as described on Wikipedia, the quality of greatness, whether physical, moral, intellectual, metaphysical, aesthetic, spiritual, or artistic. The term especially refers to a greatness beyond all possibility of calculation, measurement, or imitation. That’s a lot to live up to for a videogaem!

I’m using that term to describe games that feel like they stretch out your brain just by playing them. Usually this doesn’t mean by difficulty, although Stephen’s Sausage Roll has plenty of that, but by there being some special aspect of it. I think what I mean by that will become more evident as this series continues, but Stephen’s Sausage Roll is rather foundational. Both Jonathan Blow (Braid, The Witness) and Arvi Teikari (Baba Is You) have claimed it as inspirational. Sublime things tend to inspire people a lot.

It’s easy to miss the quality of Stephen’s Sausage Roll if you play it casually, because it’s not a game that really lends itself to casual play. SSR doesn’t ease you into its puzzles, right from the very start the game demands thorough knowledge of the consequences of its movement scheme, knowledge that can only come from failing at its puzzles many times. Stephen’s movement is reminiscent of the porter from Sokoban, but he’s got this dang fork sticking out of him, and every movement must take it into account. Steven can only move forward and backward without turning to the side, which rotates the fork around him.

Understanding how to move that fork around is essential to shoving around the sausages in each level. To solve a level, all of its two-tile-long sausages must be moved over grills exactly once in four locations: once on each tile of one side, and once on each tile of the other. Leaving a sausage on a space doesn’t overcook it, but you can’t move it so a cooked spot touches a grill again. One move for each sausage on each tile of each side! Burning a sausage, or dumping one in the water, immediately fails the level.

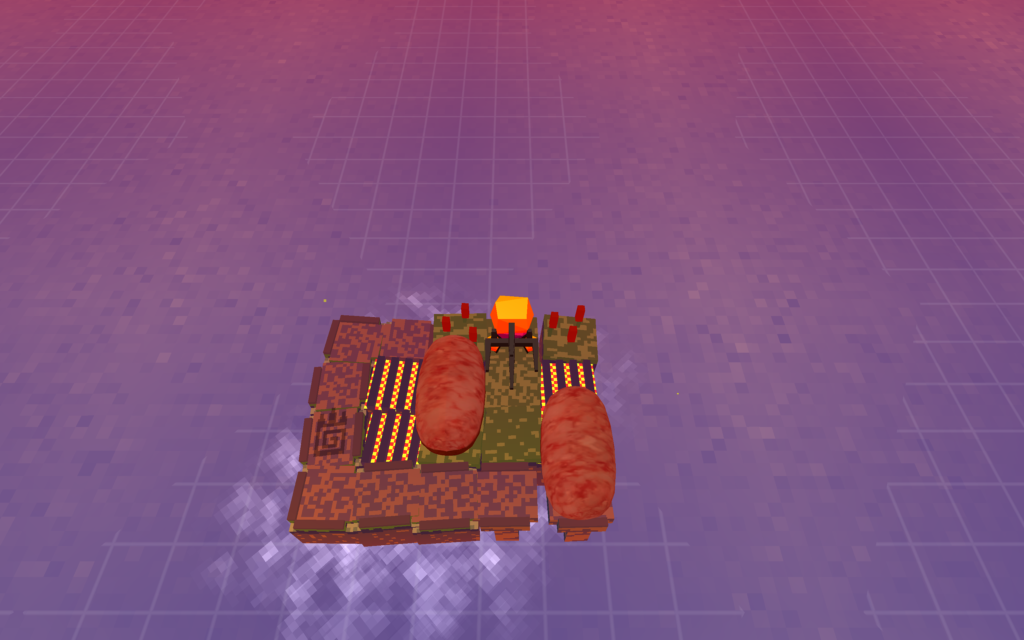

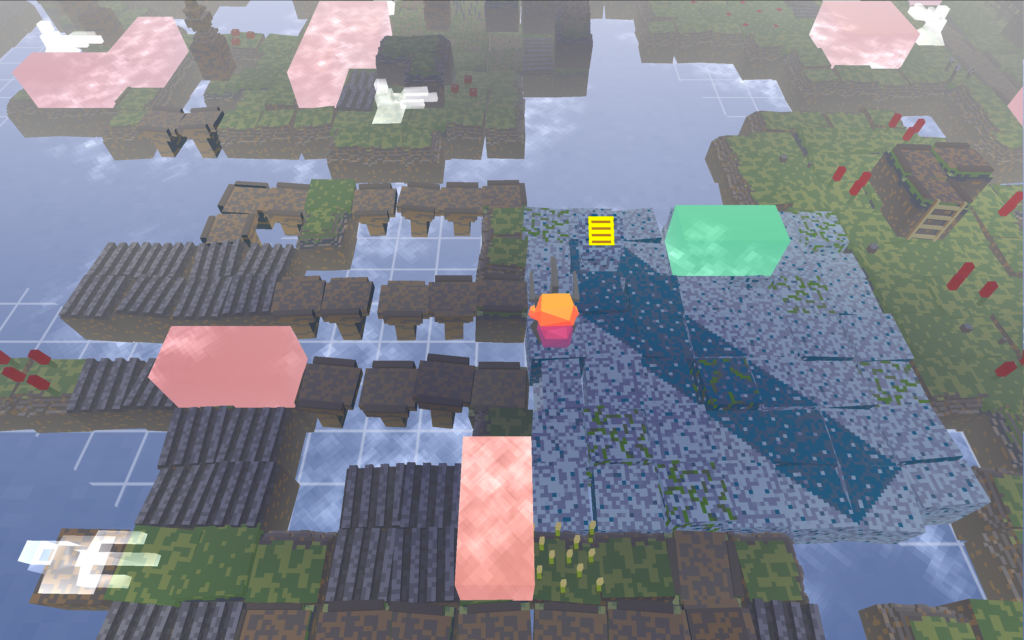

This playthrough of one early level demonstrates how it works:

This description is not all of Stephen’s Sausage Roll’s tricks, not by a metric mile, but it’ll stump most players for a good while. It starts out hard and gets harder.

There are no tutorials, not even instructions other than an early sign that tells to use the arrow keys to move, Z to Undo, and R to Restart a puzzle. (These hotkeys have become a bit traditional, and work in other games.) You can’t even read the sign until you realize you have to swing your fork around and walk alongside it. Stephen does have other moves, I have come to learn from reading pages about the game, but it’s impossible to activate them in early levels.

When I read writing about puzzle games, the writer often talks about how smart the game made them feel, sometimes in a paragraph that also mentions dopamine hits, like they were Skinner boxes that give players treats. I dislike game criticism that tries to reduce them to pop neurochemistry. Besides, these days dopamine is not in short supply. It’s available on every Steam corner, plus you could get it just as well from food, an interesting novel, a movie, or pornography for that matter. Difficult puzzle games make you work for it, and where is the fun in that?

The fact is, puzzle games are not interesting for being a dopamine administration mechanism. They are about improvement, about learning to overcome challenges on your own. Once you learn how to do Sokoban puzzles they lose their appeal, because solving puzzles isn’t as much fun as learning to solve them.

Stephen’s Sausage Roll does not make the player feel smart. It makes them feel perfectly stupid at first, but by the end of it they may feel smart. They may, because by completing it they may have become a little smarter. The improving aspects of playing video games is not often mentioned these days, but it is one of the main reasons that I enjoy them. Thinking through a difficult puzzle can help one learn to think a little better, and because of that these sausages are no mere empty calories.

But the difficulty, and the novel take on Sokoban rules, aren’t the only reasons I’m writing about this in a series about sublime games. Each of the game’s little puzzles is a small portion of a larger world. When you enter a level, most of the world sinks beneath the sea, leaving you with a tiny portion of it remaining. When you properly cook all of that level’s sausages, the world returns, but pink walls, where the sausages were, will be gone, allowing you progress. This means the very terrain of the overworld is made of the puzzles you’re solving, which is an unexpected elegance in a game about cooking sausages. And mirroring that fact, there is a deeper meaning to the sausages you’re cooking and eliminating from the world, one that is revealed slowly, as you solve each excruciating puzzle.

SSR is a game that makes a mockery of the very concept of review scores, as most sublime games do. The graphics are purposely done in a PS1 style, intentionally ugly by current standards, and the sounds are simple steps, swishes, and the occasional “ugh” that may have come from the game or the player. And it’s gameplay, while great, shows that play can be about subtracting, taking away all extraneous elements, rather than adding unnecessary new things. In what world does taking away things add points to a review score?

Stephen’s Sausage Roll is not an extremely popular game. While it inspired big hits like The Witness and Baba Is You, and is rated Overwhelmingly Positive on Steam, it hasn’t sold as well. But it hangs on, quietly enlightening new generations of players and designers. It may inspire you too, if you were to let it.