Sometimes WordPress is infuriating.

What I remember doing is working hard on a post proclaiming to the world the existence of a weird offshoot of the Pac-Man universe called Packri Monster. I wrote it, and I saved it (I believe) so it would be posted on the morning of January 16th.

Well, I just had a look and instead of the post I thought I had scheduled, there was just an empty shell, a title to an empty page. Even the name “Packri Monster” was misspelled. How embarrassing!

But what’s even more embarrassing is that I found out what I had written before had a notable factual inaccuracy, so I’m kind of glad it didn’t get out in that form.

Let’s remedy all of these things right now.

The Backstory & Coleco Pac-Man

Namco made the original Puck-Man, in Japan. Bally-Midway licensed it, changed the name to Pac-Man to avoid people messing with the P in the title, and that was when Pac-Man became a worldwide mega-hit. At the time game rights tended to get portioned off separately to consoles, home computers and dedicated handhelds. While (in)famously Atari locked up the console and (through Atarisoft) home computer rights to Pac-Man, the handheld rights went out to a variety of places.

Notably Coleco made (relatively speaking) a respectable tabletop version of Pac-Man, doing the best they could with its discrete graphic elements. You can play a recreation of that here. (Note: use WASD to control the game, the arrow keys are for Player 2.)

Coleco Pac-Man is interesting as a game in itself. Its box confidently asserts that it “sounds and scores” like the arcade game, of which I assure you neither is true. Its background noise is an annoying drone; while it usually takes two boards to reach 10,000 points in the arcade and earn the sole extra life, it took me five on my test play of Coleco Pac-Man. Even so, it’s the best handheld or tabletop version of Pac-Man from the time.

Because all of the LED graphic elements of Coleco Pac-Man’s are discrete, pre-made images, they had to take certain liberties with the in-game art. Pac-Man is drawn permanently facing left; alternate spaces on the board depict him with mouth open and closed. The dot image is repurposed as one of the ghosts’ eyes. Energizers are red, so when a ghost passes by one of those spaces one of its eyes, too, turns red. Ghosts don’t show up in different colors to identify their personalities. Each contains a Pac-Man graphic themselves, which isn’t illuminated when they are vulnerable. All of these elements are repeated throughout the board, visible dimly when inactive, and lit brightly when intended to be used as a game element.

I maintain that Coleco tabletop Pac-Man is playable. The simulation linked above has a flaw, you can’t hold down a direction to take a corner early like you could in the arcade, you have to press a key at the moment you sail past an intersection if you want to take it. But even in this form, it’s arguably a better game, in playability, than Atari 2600 Pac-Man. It sold 1.5 million units after all, despite coming out after.

It was a time when it wasn’t uncommon for companies to make ASICs (Application Specific Integrated Circuits) that could play one or more games, which they would license to other companies. General Instruments made a number of these for dedicated consoles (here’s a catalog of their products), playing a number of games, including Pong and Tank clones.

One such ASIC was made by Bandai, the same company that decades later would merge with Pac-Man creator Namco itself. It was made for a handheld that Bandai themselves would produce called Packri Monster.

Packri Monster as a Game

It’s an interesting little machine. Like Coleco Pac-Man, it uses discrete images for its graphics, which have to be mixed together in various ways to satisfy all of its play requirements.

GenXGrownUp posted a video on Youtube running down both the unit and the game (16 minutes):

Note the yellow letters on the package: PACK MAN. It’s obviously intended to be a fly-by-night knockoff, from the very company that would later merge with Pac-Man’s creator!

Differences are many. The maze is much smaller, the ghosts (“Bogeys”) are limited in number to three, and there’s only two “power foods,” in the upper corners of the maze.

The lack of one entire ghost makes sense, given the smaller size of the game. But it turns out there’s another knockoff of Pac-Man, with an even smaller maze, and a bizarre limitation. It’s the game I had originally mistaken for Packri Monster, and I wish I knew more about this variant, because it’s fairly widespread.

Mystery Handheld Pac-Man Variant #3

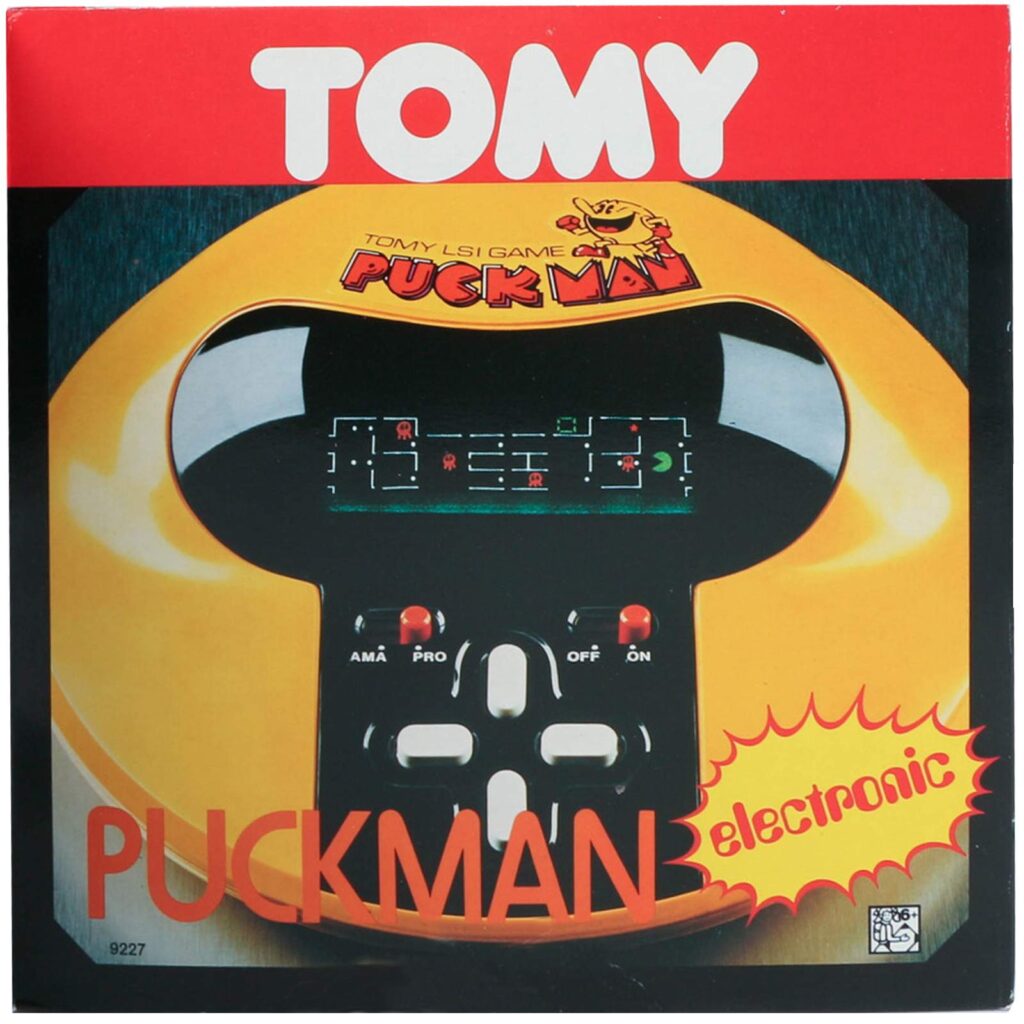

This version is probably best known as the basis of Tomy’s handheld Pac-Man game, in the appealing yellow case.

A simulation of Tomy Pac-Man is playable in MAME, and additionally can be found on the Internet Archive in playable form. It’s a simpler game than the Coleco version, and like Packri Monster tops out at three ghosts, starting at level four.

Especially notable about this version is its extraordinary difficulty, and dare I say, unfairness. There’s only 34 discrete places in the maze that Pac-Man can even be at, and two, later on three, of those places are going to contain ghosts at a time. From two to four locations can be threatened (“in check”) by the ghosts at any moment, for unlike arcade Pac-Man, these ghosts are more prone to reversing direction whenever they want. At the start of a board ghosts are prone to behaving randomly, so you can’t even devise patterns to ensure your safety. The Energizers become essential tools for survival, and expire rapidly, so you’re unlikely to ever eat more than two ghosts with one.

This is the only version of 80s handheld Pac-Man that I know of that has fruit. Graphic limitations mean that it’s always going to be cherries, but the points advance to 400 pts. per fruit on level four, where it becomes an essential component of your score. One extra life is awarded at 2,000 points.

But the weirdest thing about this version… since, like in all these versions, Pac-Man is stuck permanently facing left, and the dots are set between Pac-Man locations in this version, the unknown designer of Tomy Pac-Man decided that the player can only eat dots and Energizers when traveling left. The game isn’t about visiting every location in the maze, but visiting every dot when traveling in the right, that is left direction!

So if you’re fleeing from left-to-right, you’ll never eat any dots. It influences your travel significantly, and you’ll unavoidably often have to double back over dots to satisfy Pac-Man’s directional digestion.

When you pass level five, you get told: “good“. I don’t know if any later four-letter message await you. There aren’t enough elements for “wow”.

Like Packri Monster, Tomy version of Pac-Man’s got licensed out, but in an unusual format: at the basis for an LCD watch Pac-Man game from Nelsonic. Sum Square Stories shows off this version here. (8 minutes). There’s some substantial differences: it seems easier, scores much lower, and starts you out against only one ghost. But it retains Tomy Pac-Man’s most distinctive quirk, that eating can only be done when going west.

Why does this version of Pac-Man do that? To make the game harder? I have no clue at all. Can anyone enlighten me as to the reason?