Microsoft’s Evil Quotient (EQ) has fluctuated over the years. On the average it was trending down for a while, but their sponsorship of OpenAI, and their ruining of Windows 11 and forcing many people to buy new machines to use it, have caused it to shoot right back up again.

But they have made two significant historical contributions to open source software recently. Back in September they open-sourced the original version of Microsoft Basic, which was partly written by Bill Gates himself as a teenager. Here’s the announcement on Microsoft’s Open Source blog, and here’s the GitHub repository with the code. It’s worth noting that Bill Gates was long vocal against the principles of free code sharing, and his arguments in favor of commercialization of computer software are partly responsible for our current capitalist hellscape, but I guess better very late than never, eh what?

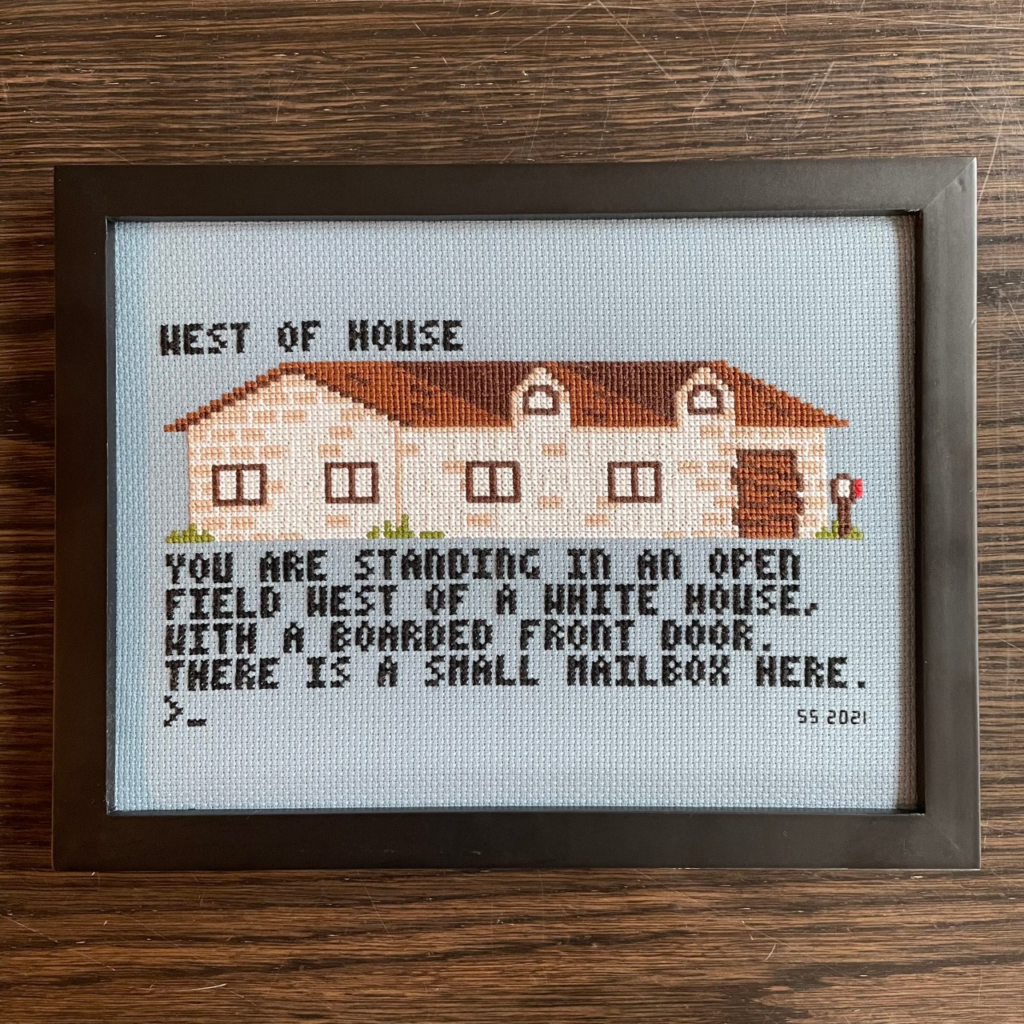

More recently, as in the 20th of this month, Microsoft announced that they were officially opening the source code for the three Zork games. The copyright for them passed into their holding by their acquisition of Activision. If you have a time machine, it’d be a fun trick to go back to the founding of Activision and tell them about the later history of their company, although in doing so you might cause them to give up their efforts in despair.

It must be said that Microsoft didn’t publish the source code to the Zork games; instead, they gave their official blessing to Jason Scott and the Internet Archive’s efforts to preserve it. They did that by adding documents to the GitHub repositories for Zork I, Zork II and Zork III. The source code takes the form of ZIL files, code written in the Zork Implementation Language to be compiled into object files compatible with Infocom’s Z Machine interpreter, so if you want to understand what that means, I suggest Andrew Plotkin’s introduction, What Is ZIL Anyway?