Set Side B’s mission statement is to cover three categories of gaming: retro, which let’s be honest is most of what we do; indie, often the province of blogmate Josh Bycer; and niche, which is usually what all the Nintendo stuff gets filed under.

Well, you don’t get much more niche than the category of CP/M gaming. CP/M, or “Control Program for Microcomputers,” is an ancient OS for 8-bit Z80 computers that recently turned 50. Half a century old! While CP/M was very popular in its era and had a lot of software made for it, much of it is obscure and hard to find now, and in histories of home computing tends to get largely overshadowed by Apple and Commodore. It’s a huge vanished scene, but it can be thought of as the DOS before DOS: the OS that would become PC-DOS, then later MS-DOS, was made as a recreation of CP/M’s API for the 8086 family of processors.

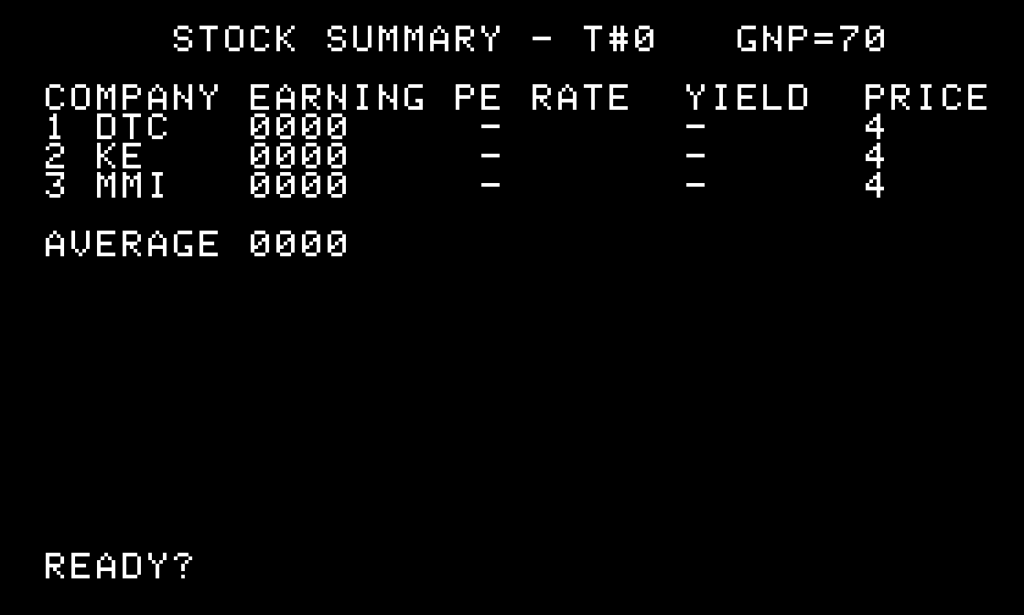

If you think MS-DOS software looks primitive then CP/M will appear to you like the freaking Stone Age. MS-DOS had early adapters like CGA and EGA for graphics, but CP/M had none of those. The point of CP/M was that it ran on a plethora of systems, from manufacturers like Kaypro and Osbourne. Many big microcomputers from the age, like the Commodore 64, TRS-80 and Atari 8-bit line, had add-on cartridges with Z80 processors in them so they could take advantage of the huge CP/M software library. Since the point of CP/M, as would be for MS-DOS later, then Windows after that, was cross-compatibility, it had to run on all those systems. But it didn’t have the IBM PC’s standardized graphics hardware, so little, if any, CP/M software took advantage of special graphics functionality. It’s all terminal gaming.

A beneficiary of the limited prospects for games on the CP/M was Infocom, which released a number of their early titles, including the Zork trilogy, on CP/M, which wouldn’t be held back by the lack of graphics. But other games were made. Many of these titles were reviewed by the ultra-niche blog TechTinkering, which has a Youtube channel, which uploaded video of a lot of CP/M software, including Mission: Impossible.

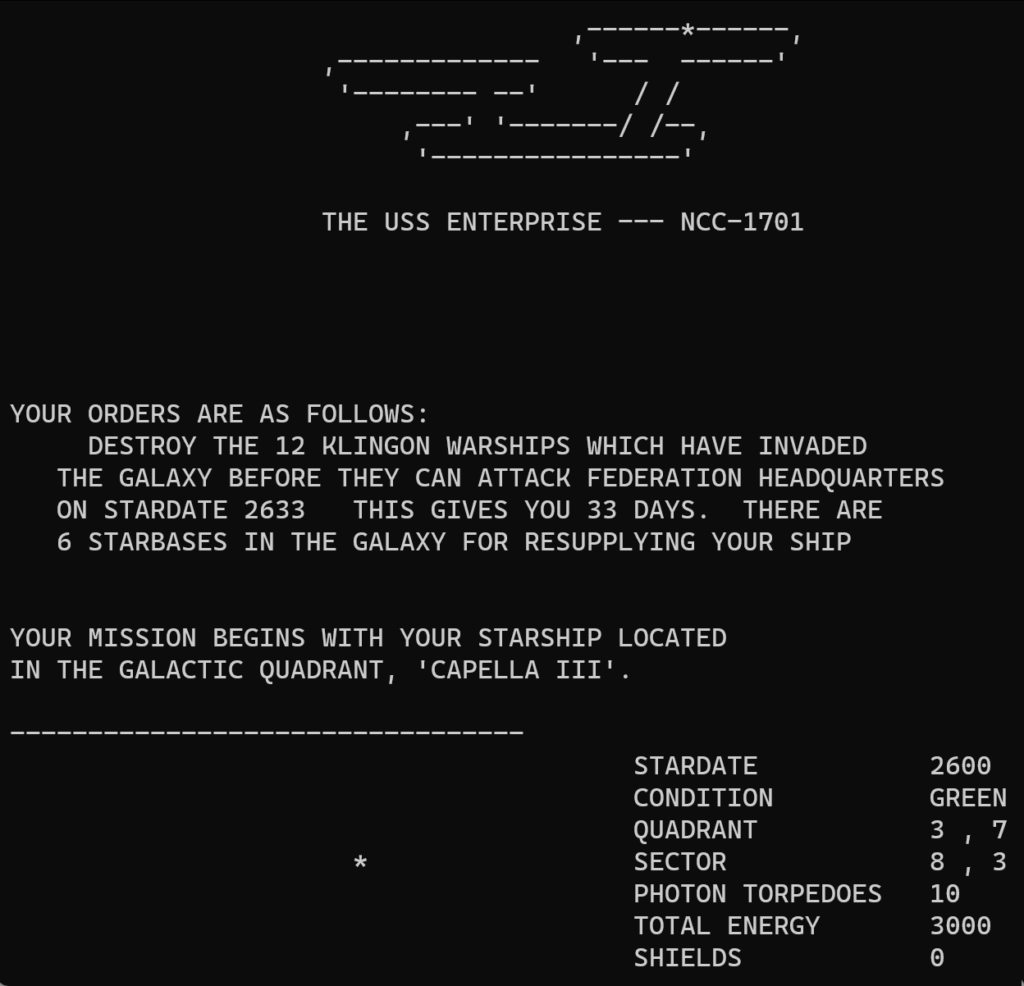

Mission: Impossible, by Richard Altman, is one of the category of terminal games, which are often played by printing information on the game state to the screen, then asking the player to enter options from a numbered list. In addition to only rarely having real-time play, because there are no visual or aural components to engage the senses, a lot of the weight has to be borne by the gameplay, which often means it’s pretty difficult. It’s of the class of games that can be found in David Ahl’s BASIC Computer Games books, games like Star Trek, Lemonade Stand and Hammurabi.

Mission: Impossible is a fairly complex game that I don’t yet fully understand. Here, watch TechTinkering’s 19-minute video on it.

Mission: Impossible (TechTinkering)