In the old old old old old old old OLD* days, people wrote computer programs by either filling boxes on paper cards or punching out squares, like they did (maybe still do?) for standardized tests. The cards would be fed into card reading devices, some of them called Hollerith machines, to be read into the computer’s memory. (Asides: Hollerith machines were invented in the 1800s. IBM’s start was in making them. IBM’s website though won’t be keen to publicize that they were used by the Nazis.)

(Another aside: What do the olds mean? Old #1: before social media. Old #2: before smartphones. Old #3: before Google. Old #4: before before the World Wide Web. Old #5: before the internet. Old #6: before online services. Old #7: before home computers. Old #8, the all-caps one: before timeshares. There is an awful lot history in the early years of personal computing that gets overlooked.)

The ultimate point after all this discursion is that paper, while little used today, is a time-honored way of entering computer programs. A while after that neolithic era, when home computers first hit it big, there grew a market for programs that weren’t as big and expensive as boxed copies on store shelves. That was the age of the type-in program magazine.

It’s the same age that that Loadstar thing I keep bringing up belongs to, but truthfully it lies only on its edges, as it was a disk magazine, created specifically to bypass the trial by fire that type-in magazines subjected its users to: sitting at a keyboard for hours, laboriously entering lines of code, or even plain numbers, in order to run some simple game, novelty, or other software. Loadstar itself served as the disk supplement, that is, media that carries all the programs from a print magazine’s issue, for both Commodore Magazine and Power/Play. (That age of Loadstar stretches from issue 9 to 61.)

I don’t know when the first magazine that published software in print form was, that’s a solid fact kind of question, there definitely was a first at some point, but there’s been tens of thousands of magazines, some of them really short-lived and obscure, and there’s a great many edge cases to look out for. Mad Magazine, to offer just one example, published a type-in in one issue.

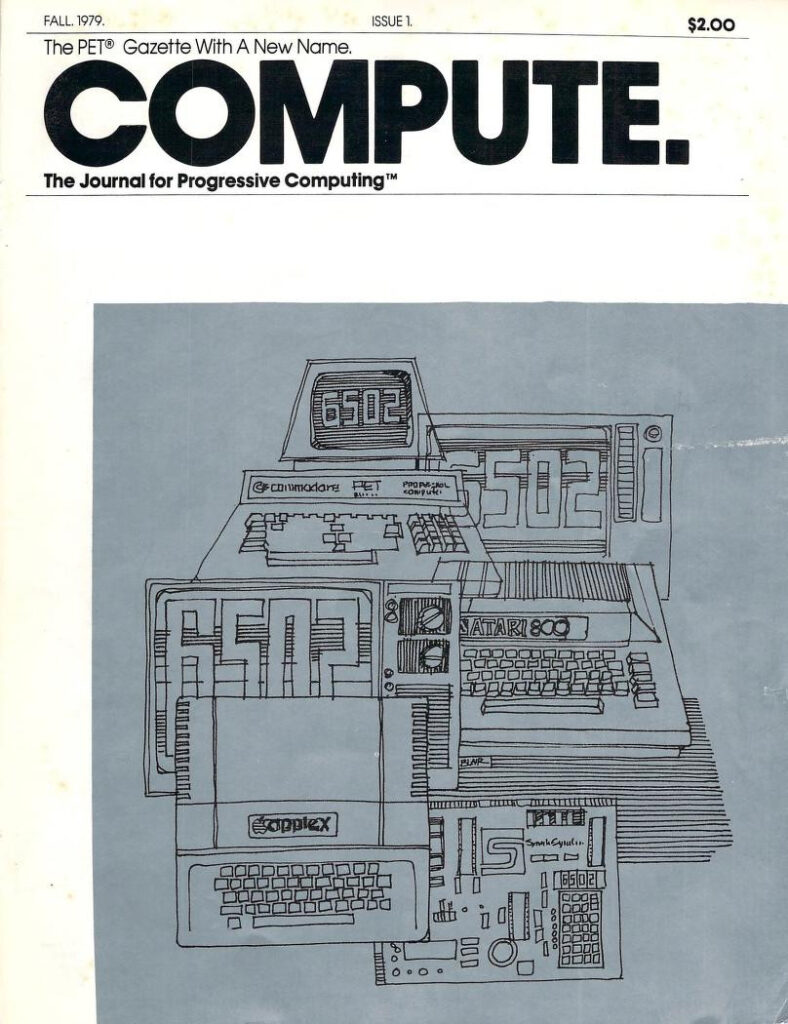

To state that solid fact definitively requires more time and resource access than I have. But a strong claim could be made for The PET Gazette.

The PET Gazette’s first issue was near the end of 1979. It was more of a fanzine, with a few aspects of a science journal, than a general magazine. It served a highly motivated and focused audience, the kind who would drop $800 in 1970s money on a machine that had 4 or 8K of RAM. The kind who thought making a machine perform automated calculation or data manipulation, all by itself, seemed really really neat. (I kind of feel that way, even now.) The kind like that, or that else bought one of the even earlier kit computers, like the KIM-1, which users had to assemble from parts, soldiering iron in hand, and for which a video monitor was a hopeless extravagance.

I would say at this point that you might know PET Gazette by its rebranding in the early 80s, to COMPUTE!, title in all caps, with exclamation point. But then I would be expecting you to say “Wow, I had no idea!” But who these days even remembers Compute? (I’m not going to persist in replicating 45-year-old marketing stylization, I have difficulty making myself type Xbox.)

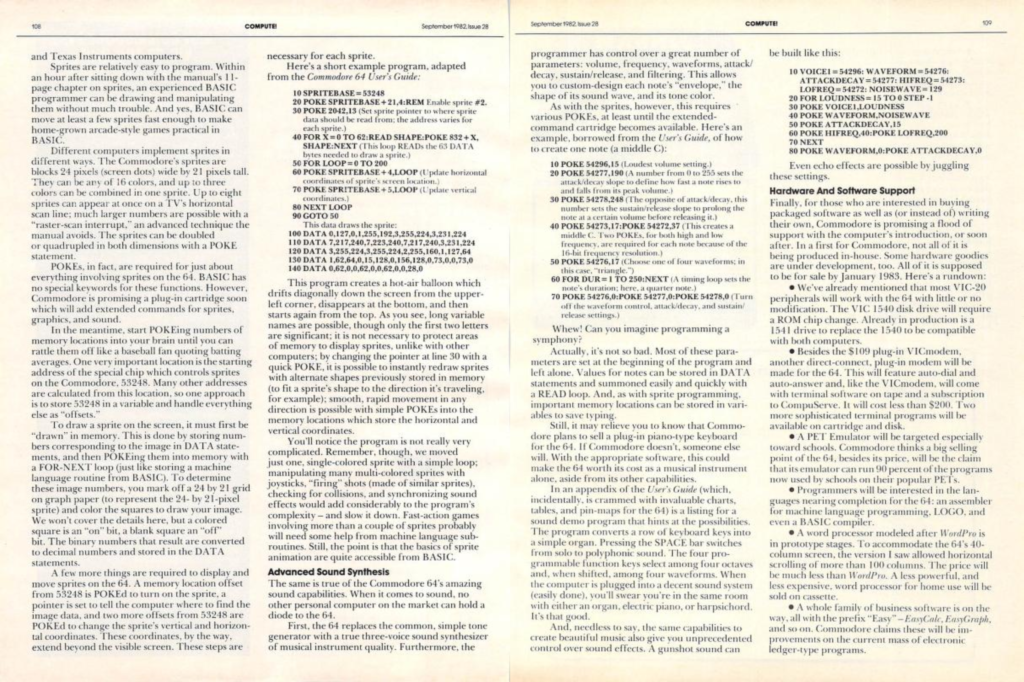

As its title indicates, PET Gazette focused primarily on the PETs, along with the KIM-1 which is like a sibling. Compute served a community of users of many different platforms, of like half a dozen: Commodore microcomputers of course, but also Atari 8-bits, the Apple line, the TRS-80s, the early days of the IBM PC, and at times even some more esoteric models.

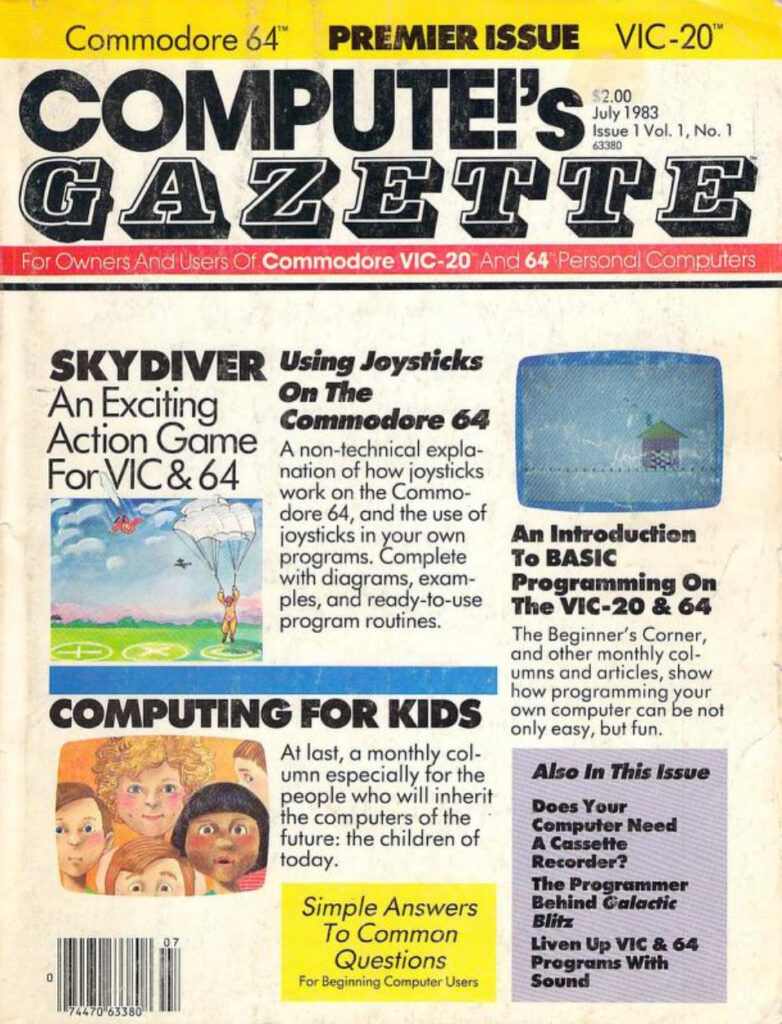

Compute soon spun off two or three subscriptions for specific platforms, for users who wanted more than what was limited, by space reasons, to one or two programs an issue. By far the most significant of these was Compute’s Gazette, its title a tribute, to those who knows, to the Compute empire’s origins.

I’ve mentioned here before, certainly, that Loadstar lasted for a surprising and amazing length of time, 22 years. Compute’s Gazette (Internet Archive) wasn’t nearly so long-lived, but it still made it pretty far. Wikipedia claims that it survived to 1995, but really its last issue as its own magazine was in 1990; then it persisted for a bit as an insert in Compute, then as a disk-only periodical.

Fender Tucker tells me that when Compute’s Gazette closed up, they paid Loadstar to fulfill their remaining subscription obligations, so at least they did right by their remaining customers. It was a dark day when CG perished, though, the former heavyweight of the type-in scene.

Some other type-in magazines of the time were Ahoy! (again, with an exclamation point):

…and Run:

The word has arrived via the Floppy Days podcast that the Compute’s Gazette may soon return. What really happened is that James Nagle saw that the trademark had lapsed and registered it himself. There’s no continuity of editor, writer or IP with the original. Yet I still hope that Nagle’s effort, which rebrands the Gazette as supporting all retro computing platforms, succeeds. His heart is in the right place at least. Here’s their website. I hope that they at least have the sense to offer a way to enter programs other than typing them in by hand; that was always the worst thing about these magazines.