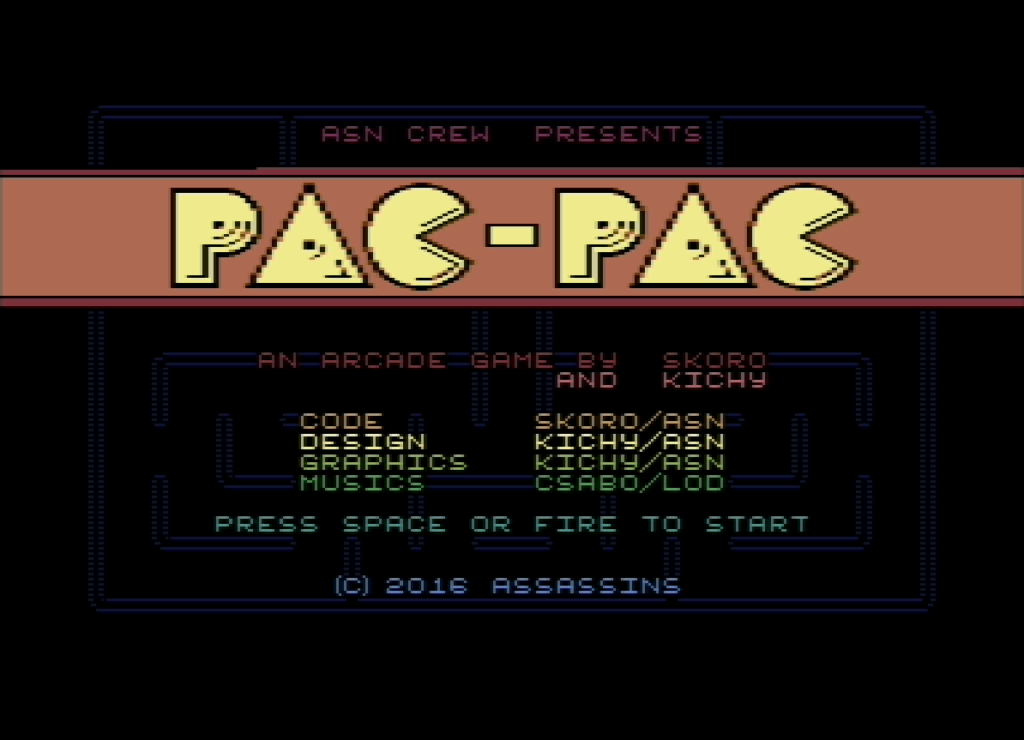

I’ve brought up the Commodore Plus/4 before, an odd system that seems poorly suited as a follow-up to the massively successful Commodore 64. It was the host system for Pac-Pac, a Pac-Man-like game made in recent years for the Plus/4, a system that’s, compared to the C64, really doesn’t seem meant for games. The video that’s our subject today is just a collection of quick views, I mean just a few seconds each, of 100 Plus/4 games, for the reason that there being even one seems like a challenge. Here is the video (17 minutes). Why? I’ll save that for after the embed.

The Commodore 64 had its strengths and weaknesses. It had hardware sprites, but only 8 of them, each with at most three colors, and even for that you had to trade off half their horizontal resolution. It had smooth scrolling, but it required the processor to move every byte of the screen itself, a feat that was actually impossible on unaided hardware within one frame’s time. (Well, there was a way to do it, discovered fairly recently, but it’s bizarrely dangerous. I’ll describe that some other time.) It had a very good sound chip for its time, but it only had three voices. It had 64K of RAM, but some of it was very difficult to access, and a quirk of the system’s design mean that some of it couldn’t ever be used by the graphics chip. And it had a floppy drive true, but in the rush to release it it ended up with a terrible flaw, making the 1541 floppy drive the slowest disk drive of all the 8-bit micros, giving rise to a whole category of fastload software.

The Commodore 64’s greatest strength was its very low price. Founder Jack Tramiel upended the calculator market with a very low cost calculator, and pulled he same trick on microcomputers with the C64, which sold for just $200 for much of its life. The Plus/4 sold for more than that for the scant year it was offered, abandoning its predecessor’s main advantage. To make up for it, it had a word processor, database and spreadsheet included in ROM. The Plus/4 was intended as a business machine, which is a shame, because businesses could afford PC clones. The C64 was properly seen as a games machine. A C64 without its game-friend features was not going to make it.

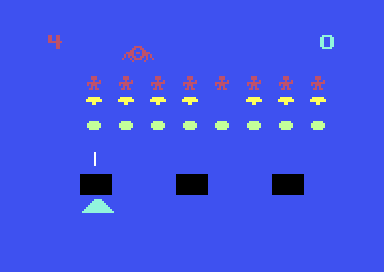

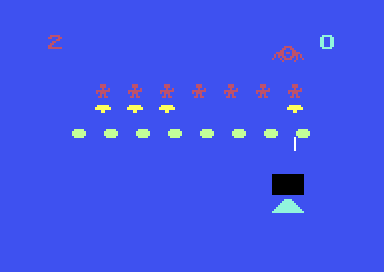

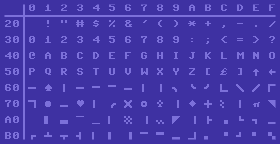

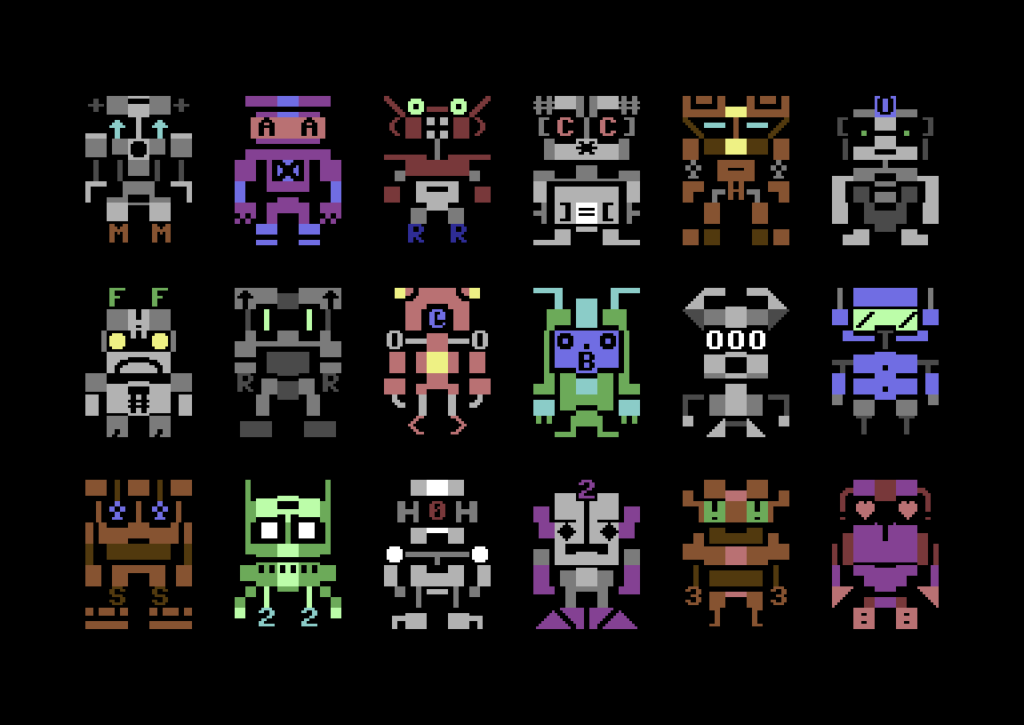

The Plus/4 had much worse sound support, no scrolling support, and worst of all, no hardware sprites. No sprites means moving objects have to be done either with tile graphics (wasteful in terms of tiles) or a bitmapped screen (slow). It did have a couple of advantages though. It had support for many more colors, up to 121 of them, and its processor, another version of the 6502, was clocked quite a bit faster.

Still, regarding games on the Plus/4, as the adage goes, it’s amazing that the dog talks at all. Every game in the video, old and new, should be regarded as something of a triumph.