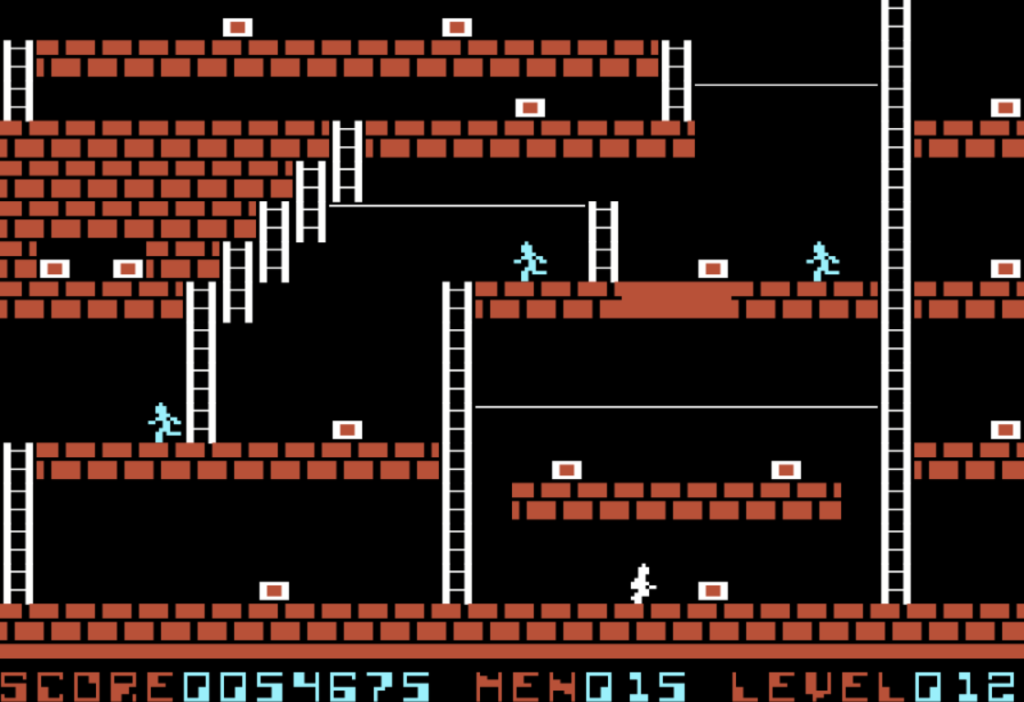

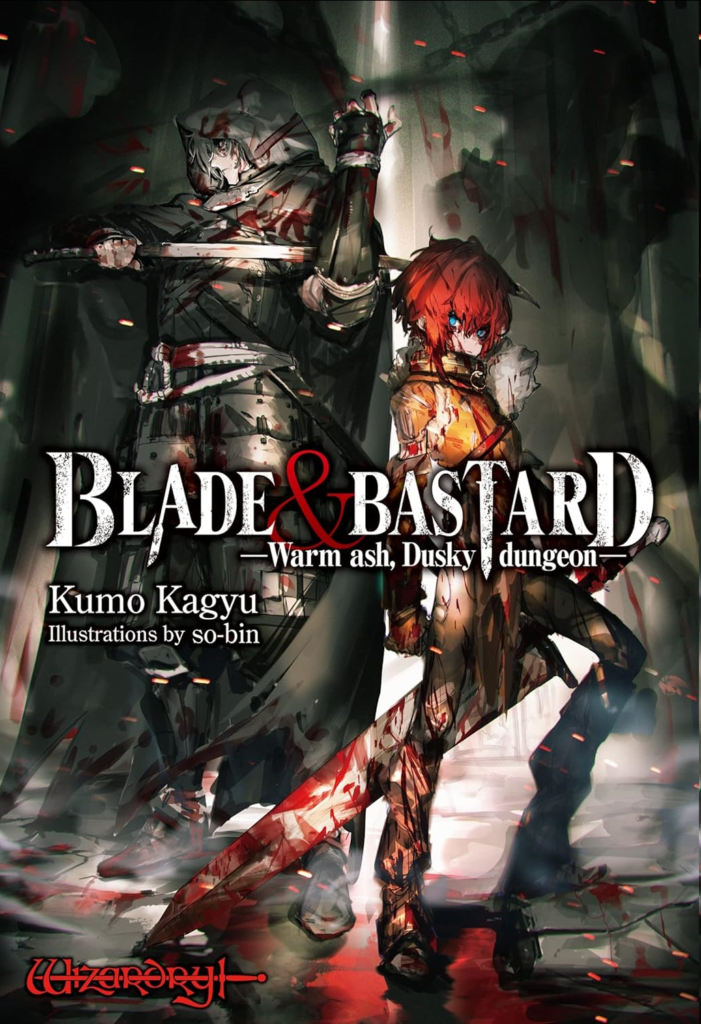

One recent thing I learned is that Wizardry, the CRPG series began in 1981, that hasn’t seen a new version from its creators since 2001, not only has seen Japanese sequels that faithfully follow the original style, but starting in 2022 and continuing today is a manga faithfully set in Wizardry’s world, called Blade & Bastard. It’s so faithful that it bears the Wizardry logo on its cover, looking similar to how it did on the 1981 Apple II box. Some logos get updated over the years, but classic computer CRPGs tend to keep theirs for the long haul.

Reading it legally at the moment, in English, isn’t possible. There is a version that can be found on Amazon, but don’t be fooled: despite its relatively large filesize, it turns out that’s just text, and each volume is pretty short, like, around 30 pages short. There are websites where you can find fan-made scanlations of the manga. I won’t link to them, but they’re not hard to find. My suggestion, if you’re interested in reading it, is to use them for now, and get the official translations of the manga when they arrive. Signs seem to indicate they may be coming in October.

I’ve not read enough to know where the story is heading, but currently it’s seemed to mostly cover the basics of dungeon exploration life. Iarumas was a corpse found sealed in a part of the dungeon that shouldn’t have had human visitors. Revived at the Temple of Cant, he (as seems common for fantasy anime and manga protagonists and JRPG heroes alike) has no memory of his past life. He makes a living bringing dead adventurers back to the temple and getting a portion of their revival fee, which is a nice nod to one of the unique aspects of classic Wizardry.

He soon picks up a couple of other party members. Most descriptions I’ve seen fixate on “Garbage,” a girl found being used as bait by dungeon monsters, who is a fierce and strong Fighter-type but talks and acts like a dog, but she mostly seems to be in it for comedy. The actual protagonist seems to be Raraja, a kid thief who had been paid to try to use a magic item to attack Iarumas in the dungeon, but the item in fact teleported both of them. The kid joins the party because, as a thief, he’s the only one who can meaningfully interact with treasure chests in the dungeon.

They also meet the “All-Stars,” the most popular adventuring group in town, a group of high-level characters who originally found Iarumas’ mummified body.

The connections to classic Wizardry are many:

- It faithfully uses the spell names from the games and their purposes, to the extent that it adds a bit extra to a couple of scenes if you know what the spells are.

- The Temple of Cant is in operation and just as money-grubbing as they are in the games.

- The MURMUR CHANT PRAY INVOKE messages are alluded to when a character is revived in the early pages.

- Dead bodies who aren’t revived turn into ash. The priest character says this means God has decided they’ve lived a good-enough life, but they take their fee all the same. In the manga story, being ashed is the end, but in the games recovery from ash is possible, but at double the cost, and if it fails too the character is gone entirely.

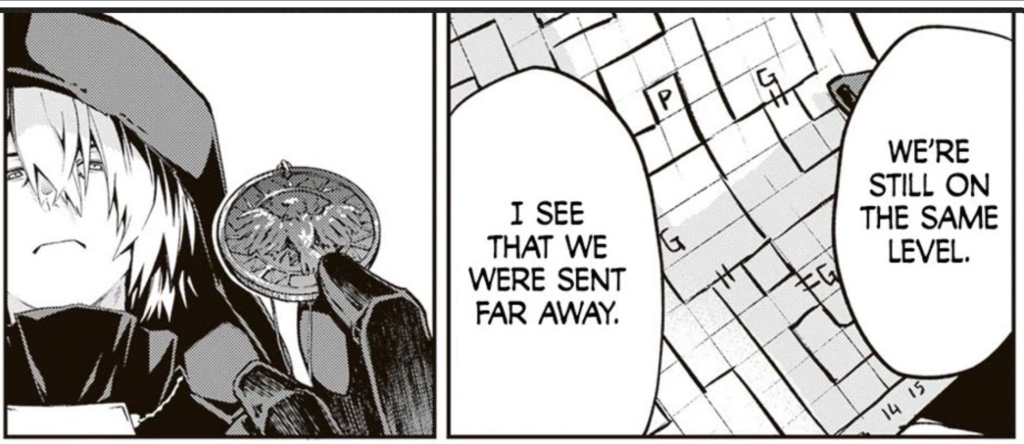

- Iarumas maps out the dungeon on graph paper!

- The characters mostly keep to their class abilities, but some are obviously multi-classed; Iarumas, for instance, seems to currently be a ninja, but he must have picked up some spells in a previous class.

- A bishop character identifies items, because if they have them identified at the trading post there’d be no profit, because the identification fee is the same as the sale price.

- The trading post is run by an elf named Catrob, which is a reversal of Boltac the dwarf, who owns the trading posts throughout the early Wizardry games.

- The Ninja is named “Hawkwind,” a reference to a character in Wizardry IV. (They may also be one of the pre-mades in Wizardry I, but I haven’t managed to get it running to check.)

- Being teleported into solid rock is mentioned at one point.

- Characters seem to be aware of alignment, and experience levels.

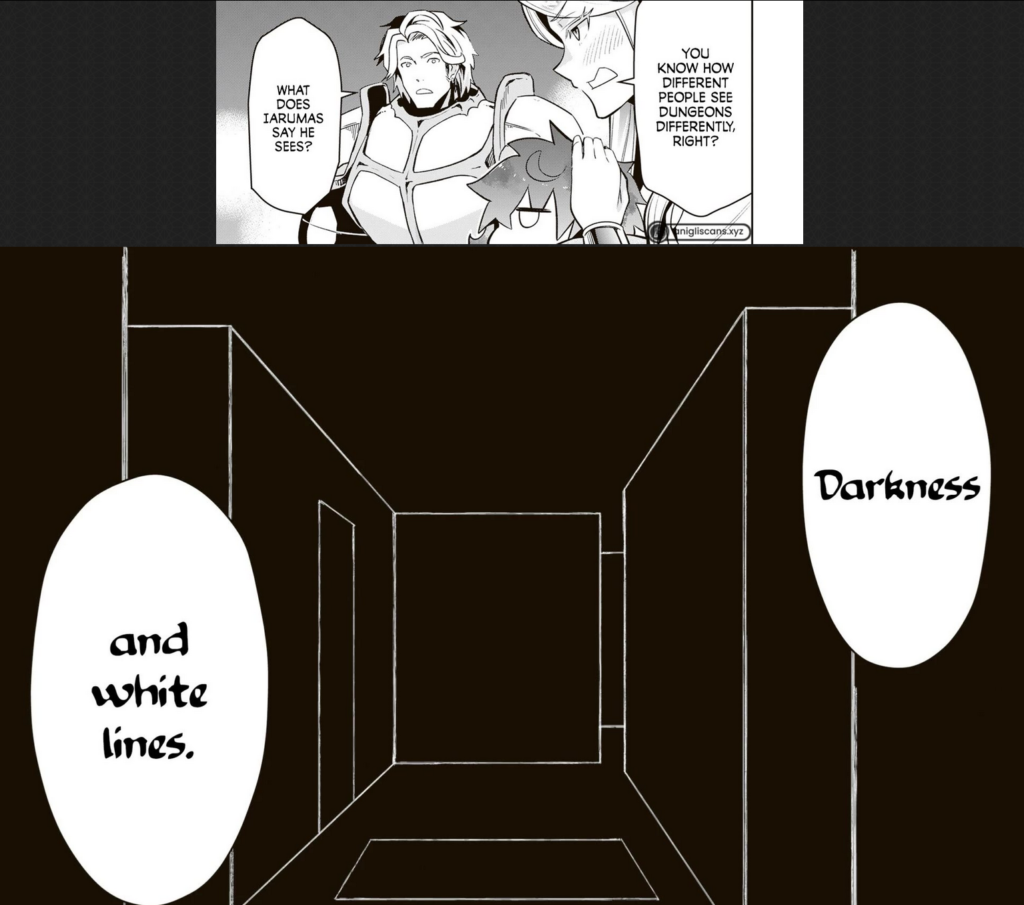

- Iarumas seems to be a character who’s a holdover from the Apple II era of Wizardry, because he sees the dungeon in wireframe!

I hope an official translation of the manga comes out before long, because I’m rather looking forward to reading it!

It was brought up by ChurchHatesTucker on Mastodon that this isn’t even the first Wizardry manga, there was one in 2009 called, in the way of manga, Wizardry Zeo. It was considered a “shounen” manga, for a target audience of young teen boys. How many teenagers in Japan were playing Wizardry in 2009, I wonder?

And there were even one or two earlier that that, called Wizardry and/or Wizardry Gaiden. There were Wizardry Gaiden games in Japan, which were alternate scenarios using the same rules but with different mazes and story, and this/these may have been a spinoff of that/those.