And so ends another year here are the weird pixel-art alien planet that our blog is based from, which for some reason concerns itself with Earth retro, niche and indie games. Hey, I never promises that our blog was thematically consistent! My first idea for its name and art theme was “Fairies and Robots,” this is a step up from that, right?

To start off, a bit of site history. Set Side B began on April 5th, 2022 with me, Josh Bycer’s Game Wisdom series, Statue (who to date has done but one post but we love them anyway), and Phil Nelson, of RetroStrange, who set up and maintains the site and cheers us on from the sidelines.

We did monthly wrap-up posts for the first few months of the site’s life, before I started forgetting to do them. Also, they’re a fair bit of work for what still feels like filler. I like to have something new here for every day, working from the theory that consistency is what matters most for a blog such as this. We’ve had a couple of lapses, but never for more than a single day. For the most part, we’ve stayed pretty steady.

In the early days of the blog I did weekly news posts, but those too felt like filler. I came to think, if you wanted to see what Kotaku was saying, you’d probably already have seen it at Kotaku. (Pretend I pronounce “Koh-tahk-oo” like videogamedunkey would say it.)

Where do we get our posts from? Well I scour Youtube frequently, obviously. It’s algorithm is not super-terrific for finding things, but sometimes comes through. There’s also social media posts and RSS feeds. (Note: Set Side B has a RSS feed too!) Once in a while I’ll post something I found on venerable community weblog Metafilter, where I often hang out. But there’s always new things to find and places to look. If you know of something that you think we’d be interested in, let us know!

What is out traffic like? We have a couple of stats packages installed, but they give very different views. One tells me we average about 60,000 hits per day, from around 11,000 visitors, but how much of that traffic is bots and crawlers, like from people trying to build datasets for their infuriating generative AIs,is anyone’s guess. WordPress’ own stats display says we’ve gotten 64,000 visitors over the past six months, which isn’t bad I guess?

Our most popular posts seem to be my link to a beginner’s guide to Balatro, my comprehensive strategy guide for UFO 50’s Party House, a quick start guide to UFO 50’s Pilot Quest, another link to a Balatro explainer, links to a Mr. Saturn Text Generator and a Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles logo generator, and one to an explanation of why the Mario 64 star Snowman’s Lost His Head sucks so much.

Most of our traffic at the moment seems to come from Google searches. It’s been much remarked upon that Google is capricious and unreliable as a source of traffic, but it’s not doing badly for us at the moment, at least.

We started Set Side B with no clear ending in mind, and we continue to keep it going for as long as we can.

So, let’s get to the recap—

(BTW, I used that em dash specifically to prove wrong the people who think it’s a sign of AI text generation. Some of us like to use all the characters.)

Set Side B updates daily, and I don’t feel up to echoing every post we made over the last year, so I’m only going over some that I consider to be highlights. In some cases, the choice for what to leave out was very difficult. For the rest, I refer you to our archives, over in the sidebar.

On New Year’s Day of 2025 I posted about the bizarre but awesome R-Type parody GAR-TYPE, where you play ace space fighter pilot Jon Starbuckle fighting against a horde of giant Garfield-shaped space monsters, which I think is about as perfect a Set Side B subject as anything.

January 17: iobaseball.com is kind of like a solitaire successor to Blaseball, which we still hold dear in our memory. Development on it seems to have stalled for now, sadly, but it’s still playable online.

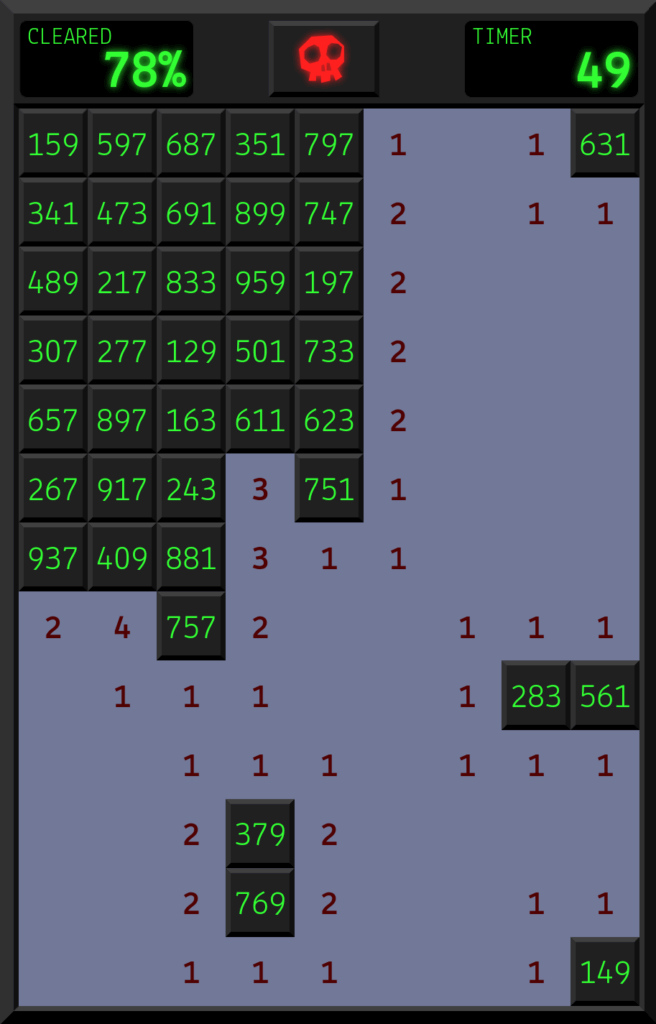

January 24 held a list of “Minesweeper-likes.”

January 27 was a link to a Roguelike Radio episode that I was in!

February 3 was about a Displaced Gamers video about them reprogramming NES Ghosts & Goblins to make it more stable.

On February 5, I hearkened back to an ancient Nethack spoiler listing the 50+ ways you could die in that game.

February 10: Rampart again.

February 18: Entertaining bits of the manual for the arcade Wizard of Wor machine.

February 24: A sad occasion, as I had finally learned that Matthew Green, online friend and booster of Set Side B from the start, and maintainer of both the website pressthebuttons.com and the podcast Power Button, had passed away two months before. Adding insult to fatality, since then long-time blogging platform Typepad shut down, and that took pressthebuttons offline too.

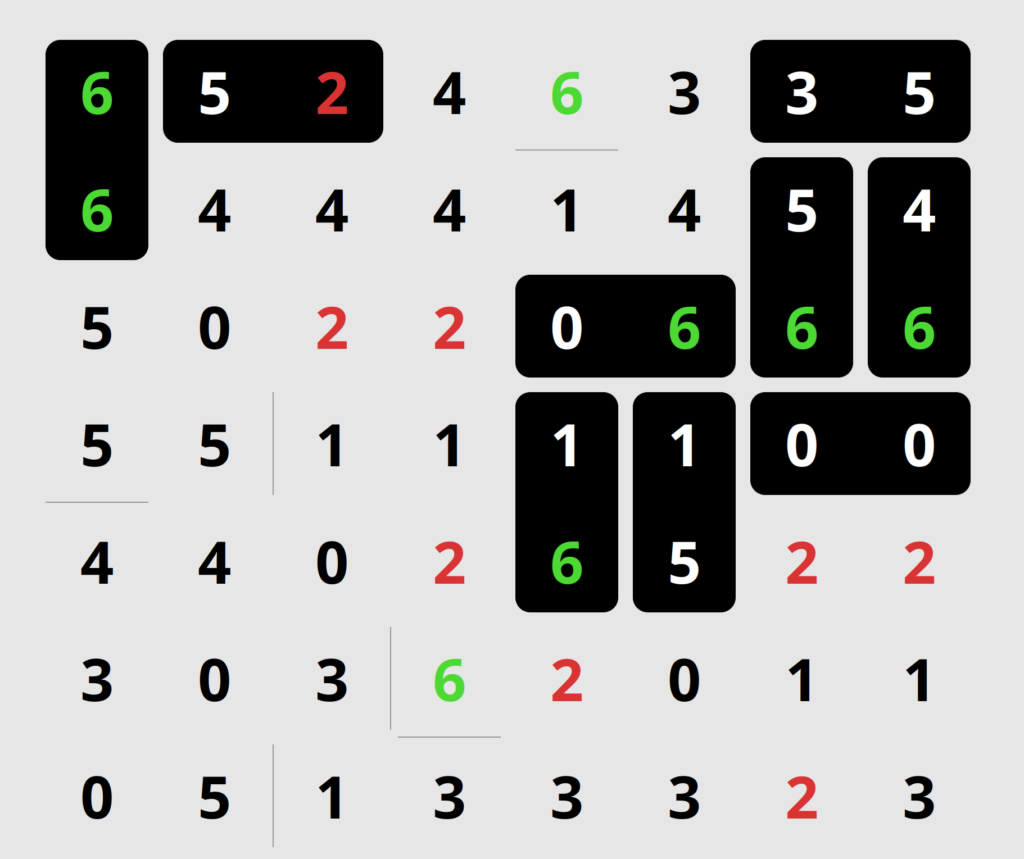

February 27: CSS Puzzle Box, a puzzle game implemented entirely in CSS stylesheets.

March 1: The amazing (if you know about its hardware limitations) Commodore 64 demo NINE.

March 6: An “arcade raid” in West Virginia, rescuing arcade machines from decay and collapse.

March 19: The basics of classic Sonic the Hedgehg physics.

March 21: On the free and open-source Simon Tatham’s Puzzle Collection, and my own tips on Dominosa, one of its many puzzles. If you’ve never heard of this brilliant piece of software you really should check it out, it’s available for nearly everything!

March 26: Long-running magazine Game Informer returns from the dead.

April 1: My own recovery and restoration of classic oldweb site Furnitures, the Great Brown Oaf.

April 4: On my favorite part of Mario Kart games, the growing number of fictional sponsors in the games.

April 12: On efforts to restore Faceball 2000’s lost 16-player mode.

April 18: More on Mario Kart World’s fake ads.

April 19: My own project to present the archives of Loadstar, classic Commodore 64 magazine-on-disk. I had a busy April. More was posted about this on May 8 and June 4.

April 27: A particularly fun Sundry Sunday find, The Legend of Beavis.

May 10: Youtube game disassembly deep-dive channel has been sleeping lately, but before they passed out they posted a gigantic and exhaustive video explaining the level format of Super Mario Bros. 2.

May 19: PAPApinball’s demonstration of expert play in Addams Family Pinball.

May 24: 8-Bit Show-And-Tell finds fake C64 programming books on Amazon.

May 27: On a particularly awesome game from that Loadstar compilation, jason Merlo’s Jed’s Journey, a Zelda-like for the C64.

May 29: I list out a whole bunch of gaming websites you should be following.

June 2: A web-wide effort to solve every 5×5 Nonogram (a.k.a. Picross) puzzle. (Update: since then the effort has been successful! Now they’re trying to solve every unique 5×6 puzzle.)

June 5: It was launch day for the Switch 2, and I was standing in line with a number of other people at the Statesboro, GA Gamestop. I was inspired, while standing, to write my own addition to the oldweb “Private Skippy” meme, listing things they (Judging by pre-existing lore, Skippy is definitely non-binary) are not allowed to do while standing in line.

June 6: I exulted Kenta Cho’s, aka.ABAgame’s terrific BLASNAKE, playable for free at itch.io! On June 25 they released another great game with Labyracer!

June 12: I wrote a piece on old-school computer type-in magazines, a major way software was distributed before the internet.

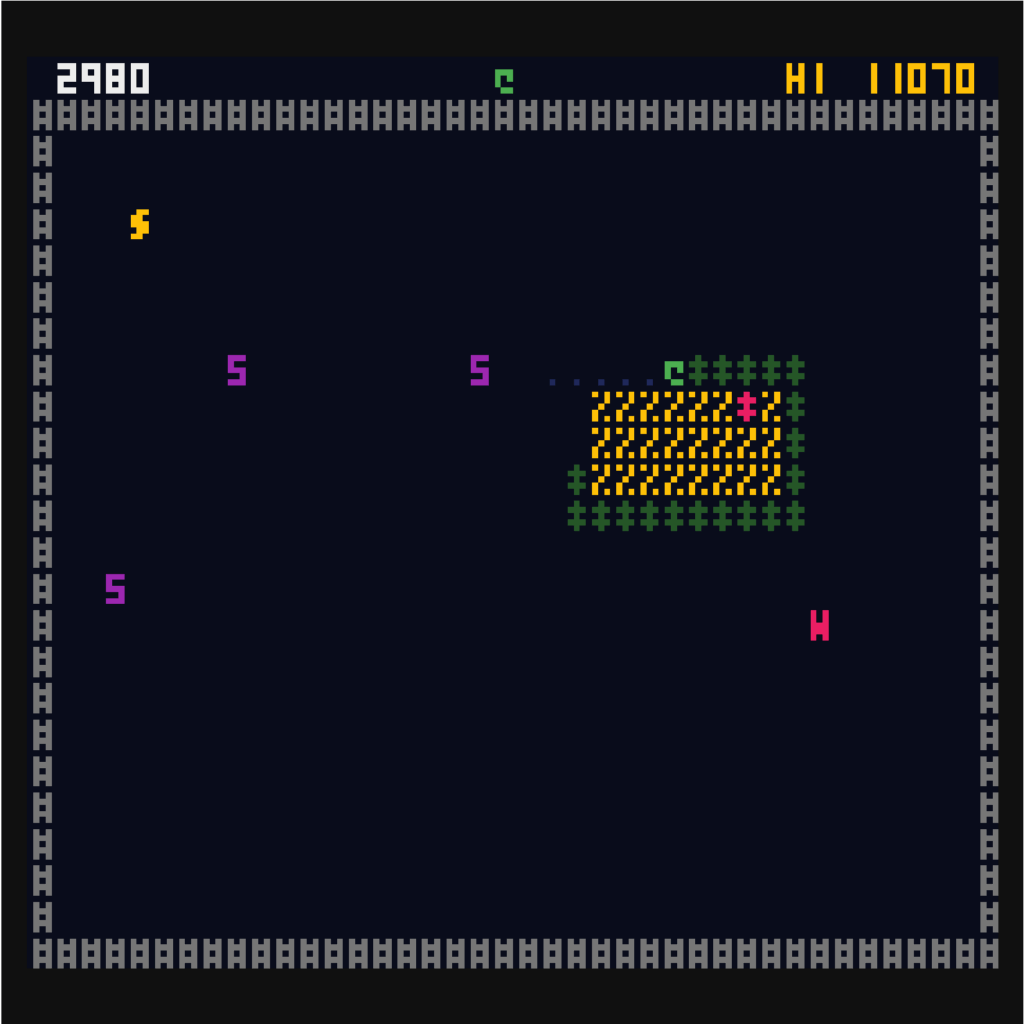

June 17: Another find from the tracks and sectors of Loadstar, Nick Peck’s terrific shooter Zorphon.

June 19: “Oh God, The Donkey Kong Country CG Cartoon Show’s On Youtube.”

June 21: The Coolest Thing In The World Is CP/M for 6502. CP/M was the OS that MS-DOS copied from. If you have a CP/M 6502 implementation for your machine, any CP/M 6502 program will run on it, ranging from the C64 to the SNES!

June 30: I had been planning to present Video Games 101’s extensive and entertaining series of retro game walkthroughs for a long while, and on this day I finally did it.

July 8: ZoomZike’s series on Identifying Luck in Mario Party is actually an extremely in-depth and thorough examination of the whole series, still in progress. Some of their videos are several hours long, and best digested in pieces.

July 9: Primesweeper is a game where your knowledge of prime numbers makes the game easier.

On July 14 I linked to Kirby Air Ride Online’s competitive scene for playing City Trial. Since then Air Riders was released, and the whole world has had the chance to see what they knew all along.

July 15: Chipwits, a remake of the classic Mac programming puzzle game, entered full release on Steam!

July 17: A guide to the various “new media” websites out there, from Defector to Second Wind.

July 23: Multiplayer Balatro!

August 1: I presented my website where I extracted all of Jerry Jones’ recipes from off of Loadstar, food recipes, and made a website for them all.

August 2: Jean and Zac’s 100 Facts about Gauntlet Dark Legacy.

August 6: Digital Eel’s Bandcamp Albums.

August 7: If you read the town sign in the original Animal Crossing while holding a damaged axe, it’ll reset it’s durability.

August 9: Nothing short of eye-popping, a madperson is had build a Wolf3D-style 3D ray tracing engine for the Commodore PET, a machine not only without bitmapped graphics, but whose character set is locked in ROM. Later on August 27, we found a PETSCII platformer.

On August 15, we started carrying a small ad image in the upper-right of the page. We don’t receive any money from this at the moment, and probably never will, but the ad is from a small-site network, one that mostly links webcomics, and it felt like a way to do our part to help spread the word about little sites. This is also the day where more news came to light about a bug I had long known about, in the NES port of Pac-Man.

September 10: Use a Gameboy Advance as a controller on the Nintendo Switch, for real, no wiring or unofficial hardware needed, although you do need quite a lot of official hardware, including a Gameboy Advance to Gamecube cable and the USB Gamecube controller adapter.

September 20: A talk on how to turn a boring Chromebook into a full laptop.

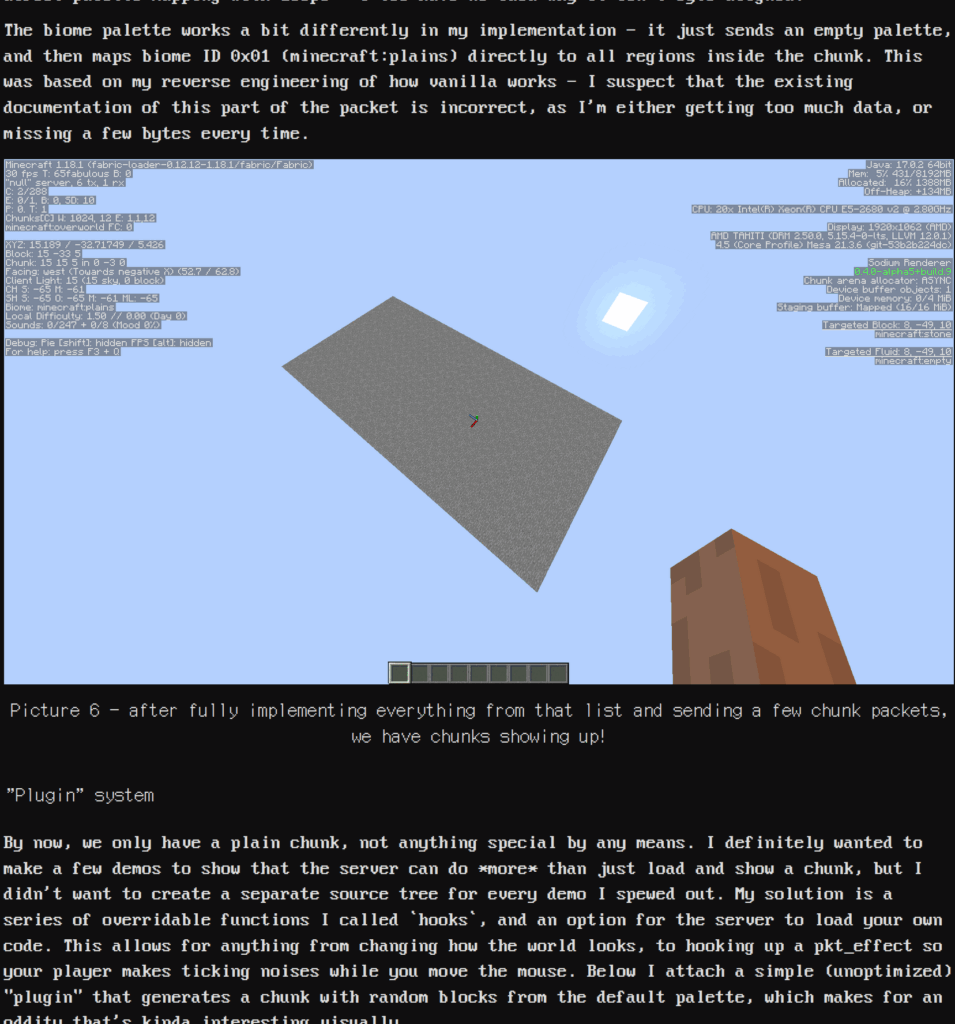

September 23: Oh, nothing. Just a Minecraft server written in bash.

September 25: Someone found an old-time penny arcade in Yorkshire and tried out a lot of their games, most of them ancient electro-mechanicals. The next day we saw one of Konami’s weirder redemption machines, the unexpectedly cool Picadilly Gradius.

September 29: Long-time classic Final Fantasy and Squaresoft fansite Caves of Narshe! On October 4 I linked to three more old Final Fantasy sites.

September 30: Adrian’s Digital Basement found a long-dormant cheat for NES Galaxian that makes it much more fun to play!

October 7-11 was a week of tips for classic arcade games. Oct 7: Phoenix and Centipede. Oct 8: Donkey Kong. Oct 9: Robotron 2084. Oct 10: Defender. Oct 11: Q*bert. A few days later on October 14, Mappy. And returning to Donkey Kong on October 30, how to beat those damn springs.

October 17: The great homebrew game Mega Q*bert for Genesis/Mega Drive.

October 21: The charming, award-winning text adventure Lost Pig (And Place Under Ground).

October 29: A Korean Youtuber uses a 3D pen to make excellent models of video game characters.

October 31: On Halloween, Castlevaniastravaganza!

October 5: The official SkiFree homepage. And also, the Kickstarter for Greg Johnson’s Dancing With Ghosts, which was successful!

November 13: A completely different madperson than the 3D engine on a PET one did a respectable port of OutRun to the Amiga.

November 20: Eamon, classic Apple II community-made modular text adventure RPG series.

November 22: I fear it’s a Kirby Air Riders Review.

November 29: Mechanical hand-held games.

December 3: Websites about Conway’s Game of Life.

December 6: Yacht and Panic’s wonderful 90s cable TV simulation (on another planet) Blippo+!

December 12: Jamey Pittman’s tutorial on grouping Pac-Man’s ghosts, an essential skill to develop to get high scores without patterns.

December 17: In Ocarina of Time, leaving Kakariko village at the wrong moment during a rainstorm makes Hyrule go crazy.

And on December 27, a rare recording of a talk given by several microcomputer luminaries, including Steve Wozniak and Jack Tramiel

Thanks for reading Set Side B in 2025! We look forward in 2026 to bring you more from the Flipside of Gaming.