Quick post today, here’s a 15-minute anime uploaded by Kineko Video, transcoded from a VHS tape, about the adventures of various Dragon Quest monsters. It is fun in ways that only classic anime tends to be!

Tag: dragonquest

Kit & Krysta Explore a Secret Game Dev Hangout in Tokyo

I am SO ENVIOUS. Kit & Krysta, formerly of the official Switch video podcast Nintendo Minute, currently of their own projects and Youtube channel, got cell phone video of an amazing place, a location in Tokyo somewhere that gamedevs sometimes meet at, and is crammed tightly with game memorabilia. It’s almost a museum all to itself, and unlike the Nintendo Museum, seems like they don’t mind video footage escaping their confines, although on the other hand this doesn’t seem to be open to the public. It doesn’t look like a lot of people could fit in there at once, anyway!

I usually steer well clear of the hard sell, or “prompt for engagement,” when it comes to asking you to follow links and view videos from here. I figure if you’re interested you’ll click through, and if you’re not, then maybe tomorrow. But I’m breaking through that reserve just this once, as this place is amazing. You really have to see this if you have any interest in Nintendo, APE, Pokemon, Dragon Quest or their histories (12 minutes):

Our Private Tour of the Top Secret Nintendo Game Developer Hangout in Tokyo (Youtube, 12m)

Who the Heck is Dragon Quest’s Mutsuheta?

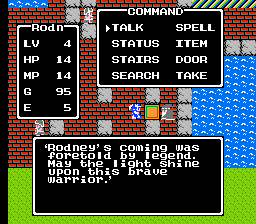

Kurt Kalata’s Hardcore Gaming 101 posted an article telling us about Mutsuheta, renamed Mahetta in the English localization for the NES. Mutsuheta is one of those figures who only appeared in the original game’s manual. Mutsuheta was the prophet who foretold that a descendant of the great Loto/Erdrick would arise and defeat the armies of the Dragonlord. Other than his mention in the manual, however, he doesn’t appear in any of the games of the Erdrick trilogy, and never appeared onscreen until the first Dragon Quest Builders, where he’s an NPC. He was renamed Myrlund in its English translation, but in Japanese he’s got the name of the character from the manual.

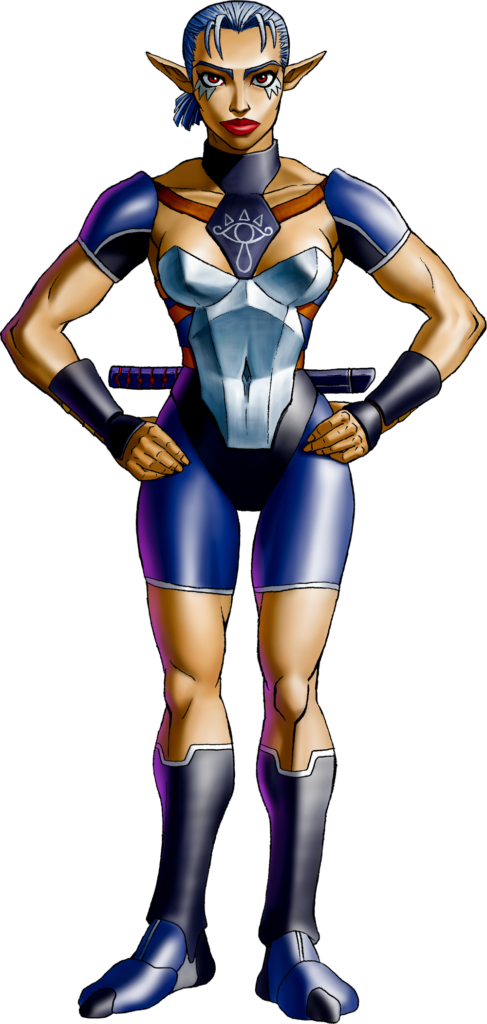

Reading this, I was reminded of https://zeldawiki.wiki/wiki/Impa, Zelda’s nursemaid/servant, who was a similar kind of manual-only backstory figure until Ocarina of Time, where Impa not only appeared as an important NPC, but was revealed to be of the secretive Sheikah tribe, and had ninja skills to boot. She looked a lot different from the aged figure in The Legend of Zelda’s manual.

Time Extension: Why Do So Many Japanese RPGs Use European-Style Fantasy Worlds?

Time Extension has come up here a lot lately, hasn’t it? It’s because they so often do interesting articles! This one’s about the propensity of Japanese games to use medieval European game worlds, the kinds with a generally agrarian society, royalty, knights, and their folklore counterparts elves, dwarves, fairies, gnomes and associated concepts.

They often fudge the exact age they’re trying to depict, with genuine medieval institutions sitting beside Renaissance improvements like taverns and shops. Nearly of them also put in magic in a general D&D kind of way, sometimes institutionalizing it into a Harry Potter-style educational system.

Notably, they usually choose the positive aspects of that setting. The king is usually a benevolent ruler. It’s rare that serfdom and plagues come up. The general populace is usually okay with being bound to the land. The Church, when it exists, is sometimes allowed to be evil, in order to give the player a plot road to fighting God at the end.

Hyrule of the Zelda games is likely the most universally-known of these realms, which I once called Generic Fantasylands. The various kingdoms of the Dragon Quest games also nicely fit the bill. Final Fantasy games were among the first to question those tropes, presenting evil empire kingdoms as early at the second game.

(All images here from Mobygames)

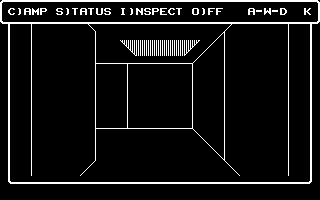

John Szczepaniak’s article at Time Extension dives into the question by interviewing a number of relevant Japanese and US figures and developers, including former Squaresoft translator Ted Woolsey. I think the most insightful comments are from Hiromasa Iwasaki, programmer of Ys I and II, who notes that this Japanese conception of a fantasy world mostly comes from movies and the early computer RPGs Wizardry and Ultima, that the literature that inspired Gary Gygax to create Dungeons & Dragons (which in turned inspired Wizardry and Ultima), especially Lord of the Rings and Weird Tales, were generally unknown to Japanese popular culture. Developer Rica Matsumura notices, also, that there is a cool factor in Japan to European folklore that doesn’t apply, over there, to Japanese folklore.

It’s a great read, that says a number of things well that have been bubbling up in the back of my head for a long time, especially that JRPGs recreated both RPG mechanics and fantasy tropes at a remove, that they got their ideas second hand and, in a way similar to how a bunch of gaming tables recreated Dungeons & Dragons in their own image to fill in gaps left in Gary Gygax’s early rulebooks, so too did they make their versions of RPGs to elaborate upon the ideas of Wizardry and Ultima without having seen their bases.

Why Do So Many Japanese RPGs Take Place In European Fantasy Settings? (timeextension.com)

U Can Beat Video Games: Dragon Warrior III

I’ve been waiting for this one for a long time! U Can Beat Video Games has finally covered the best NES Dragon Warrior, the third game in the series. It was Dragon Quest III in Japan, due to some trademark issue with TSR I think. IV isn’t bad, and has fun characters, but there aren’t as many variant strategies in it, and in the last chapter you don’t get to control the actions of most of your party members. DWIII always gives you full control of your characters, plus it lets you create characters with names and classes of your choosing, meaning, like the first Final Fantasy, you can make completely custom parties and play the game in many different ways. It was the game that spawned the urban legend that the Japanese government requested that Enix release Dragon Quest games on weekends, because so many people ditched work to stand in line to buy it. (I don’t know if it’s true, but the story has often been passed around.)

It’s also the first Dragon Quest/Warrior game that allows for class changing, which resets a character to Level 1 (similar to an human AD&D character who dual-classed), but only halves their stats, and lets them keep all the spells they learned. Since they’re Level 1 again, they gain levels very rapidly for a while, allowing them to quickly surpass their previous heights. It’s kind of an early version of the “prestige” mode of clicker games, where you reset all your progress in exchange for faster progress afterward!

It also has a cool story that eventually connects with the first two games, and has a good variety of activity, including growing a town from scratch like 25 years before Breath of the Wild and betting on monster fights! It’s also got all the challenge of the early Dragon Quest games, with later monsters who can cast instant death spells on everyone in your party at once, as well as doing other horrible things to them.

Because Dragon Warrior III doesn’t pull its punches against the player, the various tricks that the narrator does to use the engine’s bugs against it feel like playing fair, and yet, even with full knowledge of the game and multiple player leveling and cash gaining strategies he still has problems once in a while. It’s a really tough game!

This may end up being U Can Beat Video Games’ magnum opus, at least of the NES era, it’s a really long game that takes three videos, of almost 12 hours total length, to cover in its entirety! Here they are:

EPISODE ONE: Creating Your Party Through to Getting the Ship (3 hours, 59 minutes)

EPISODE TWO: Getting the Ship through to Defeating Archfiend Baramos (4 hours, 22 minutes)

EPISODE THREE: The Dark World to the Final Boss, Plus Extras (3 hours, 35 minutes)

Please enjoy, and Rubiss help us all!

Romhack Thursday: Dragon Warrior x10

On Romhack Thursdays, we bring you interesting finds from the world of game modifications.

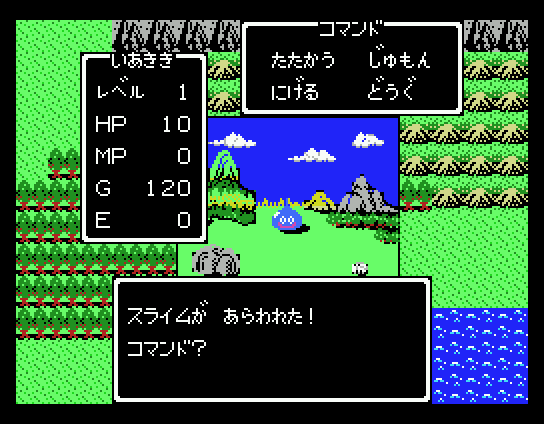

The early days of JRPGs contain many games that are kind of difficult to play today. The genre was just getting formulated, and while there was a lot of ingenuity and interesting ideas being played with, there were also many games where difficulty, and grind, were the entire point. When a game as simple as Dragon Quest, known first in the US by its localized title Dragon Warrior, had to justify its sale price, it had to present players with an experience that would be as long as a challenging NES platformer, or longer, within its limited memory space, and it did so with grind, asking players to accept fighting hundreds of monsters one-on-one in a basic menu-based combat simulation as fun enough to make up for most of the game.

At the time, in Japan, it worked, but it’s telling that Dragon Quest II has much deeper combat, and many more kinds of monsters, than its predecessor had. Dragon Warrior had a tough time breaking into the US market because of its simple gameplay, enough so that eventually Nintendo, who published the game in North America, resorted to giving away copies as a subscription premium for Nintendo Power.

What was a tough sell to Western players even then is much more difficult to enjoy now. Compare it to the much deeper, not to mention longer and better animated, titles made later in the series. It’s mostly enjoyable only for nostalgia factor and historical interest.

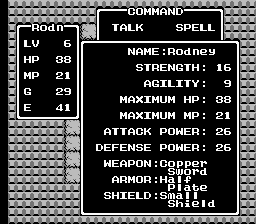

I’m not going to claim it fixes everything the game, but this hack improves its play a lot by decreasing gold prices and experience requirements ten-fold. It decreases costs: changing the earn rate of these quantities would very quickly hit Dragon Warrior’s fairly low variable caps, since the game stores both in 16-bit values. You can take the 120 gold you get from the King’s chest, buy an 18 gold Copper Sword in Brecconary, then run to the north-west to Garinham and buy the sturdy Half Plate armor for 100! With these items, even at low levels, you should be able to vanquish all of the enemies in this section of the map, except perhaps Magicians, whose Hurt spells bypass armor. But it only takes defeating one Slime to reach Level 2, two more for Level 3, and two more than that for Level 4. Slimes won’t suffice for long, but by that point you can munch on much stronger foes. This greatly reduces the number of fights a player must win to complete the game, and makes it possible to finish in less than two hours.

Preserving some modest amount of challenge, the gold costs of Inns are left the same, making them effectively ten times more expensive. Inns were never very expensive in the unmodified game, so this makes staying the night to restore your HP and MP more of a strategic choice. A tip: remember there’s a guy in Tantegel Castle who will restore all your MP for free!

If even a two-hour Dragon Warrior is too much effort for you, you could watch this playthrough of the hack on Youtube, which is about an hour and a half in length:

romhacking.net: Dragon Warrior – 10x Experience and 10x Gold