Let’s get the video embed out of the way first. Pow!

Super Mario Bros. 3 has two significant minigames (outside of two-player mode), and the inner workings of both are explained in this video.

In most worlds there are “Space Panels,” which provide a slot machine minigame for extra lives. If you’ve ever tried them, you might have noticed that it’s extremely difficult to win anything at it. Well, the video explains why that is: there’s a significant random element to stopping the wheels. In particular, the last wheel has so much randomness in when it actually stops that it’s actually completely random what it’ll stop on! So much for timing!

I have a theory (which I explain in a comment on that video) that the slot machine game was made so random because of the quality of the reward (it’s possible to earn up to five extra lives at it), and because they had played around with life-granting minigames before. Doki Doki Panic, which got reskinned for overseas markets at Super Mario Bros. 2, has a slot machine game, “Bonus Chance,” that appears after every level. With good timing and practice Bonus Chance can be mastered, earning up to five extra lives for every coin plucked in the level. I have managed to abuse that game to earn so many extra lives that the game ran out of numbers for the tens’ digit of the life counter, sending it into letters of the alphabet. There’s certainly no danger of that in Super Mario Bros. 3.

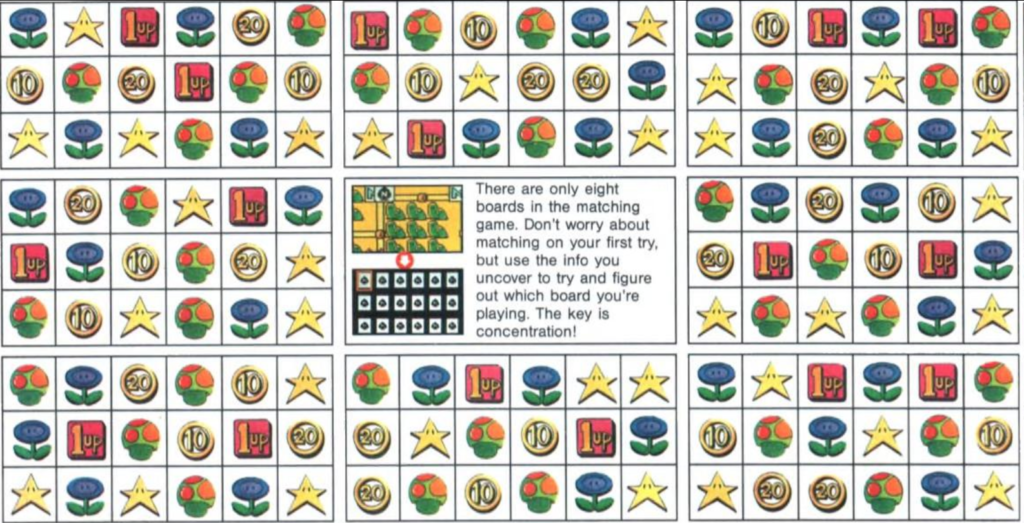

The second minigame has the player match cards from a grid of 24. Each pair of cards found earns a modest prize, from as little as 10 coins up to a single extra life. Most of the awards are powerups for the player’s inventory. The player gets two tries, but if they don’t clear the board it’ll carry over to the next time they play. Attempts at the card matching board appear every 80,000 points the player earns, making it the only Super Mario game to actually reward scoring lots of points.

The card matching game is one of the most interesting minigames in all of the Mario series. There’s only eight layouts for the cards, the second and fifth cards of the middle row are frequently both the 1UP card, and the last three cards on the bottom row are always Mushroom, Flower and Star, in that order. This means the minigame can be mastered, and even if you don’t memorize all eight layouts to deduce where the prizes are, knowing the three cards that never change usually means it won’t take more than two or three attempts to clear the board, netting lots of powerups.

Retro Game Mechanics Explained looks into why the card matching game works the way it does, and discovered some interesting things. There’s actually code in the game to do a much more thorough randomization of the cards, but it goes unutilized. The full details are in the video, but in summary:

- The board always begins in the same state,

- the last three cards on the bottom row are left unchanged, probably on purpose,

- the first way the other cards are scrambled shifts them one space in sequence, and is only done one or three times, three times in total,

- and the other method of scrambling them, which involves swapping around three specific cards, is done exactly once between each shift.

The only variation in the steps is from the choice of whether to shift once or thrice, each of those three times. Thus, there are only 23 possible layouts, that is, 8. There is a loop in there to potentially vary the number of times the cards are swapped (the second way to scramble the cards), but the way it’s written the loop is never used, and the cards are swapped only once each time.

What I also find interesting is, this isn’t the only Nintendo to use a minigame that involves mixing up hidden prizes. Kid Icarus’ Treasure Rooms also have a limited number of layouts, which vary for each of the game’s three worlds. The player can open pots in the room to collect minor items, but if they open the wrong pot early, before opening all the others, they find the God of Poverty, and lose everything they’ve found. If they can save that pot for last, though, the final pot will instead contain a pretty good prize, which can even be a Credit Card item that cannot be obtained otherwise.

The way they’re designed, both Mario 3’s card-matching game and Kid Icarus’s Treasure Rooms have tells, specific spots that can be revealed to identify which of the limited number of boards that version of the game is using, and that the player can use to get all the prizes. Also, there are Nintendo-published guides that reveal all the layouts, in Nintendo Power for Kid Icarus (recounted on this charmingly old-school webpage), and the Nintendo Power guide for Super Mario Bros. 3 (on page 10), so Nintendo had to have been aware of the limited nature of the board layouts, and may have actually intended them to be defeated with a good strategy.

SMB3 Roulette & Card Matching Games Explained (Youtube, 20 minutes)