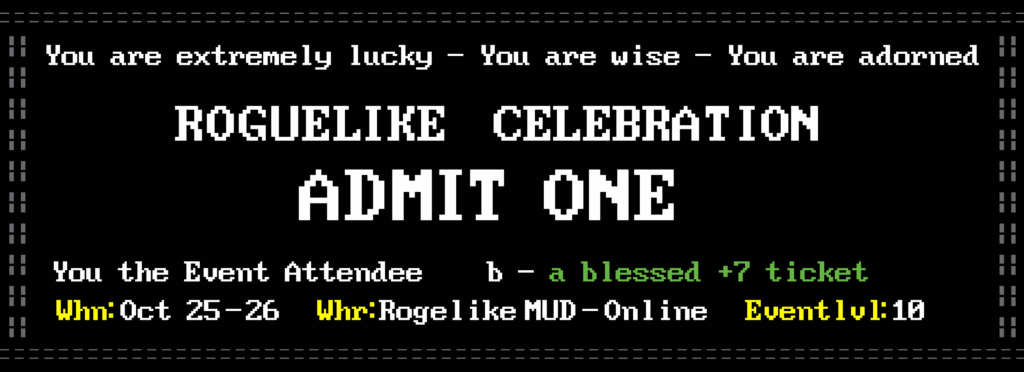

It’s a time for annual reminders, so here I am holding up a sign, reading “ROGUELIKE CELEBRATION THIS WAY ->“. And another sign, “<- ROGUELIKE CELEBRATION SHOP’S OVER HERE!” And a third sign, “ROGUELIKE CELEBRATION STEAM SALE AROUND THAT CORNER ⤷!” Yes, I’m carrying three signs. It’s a trick I picked up from Zaphod Beeblebrox.

This year it’s happening between Saturday and Sunday, October 25-26. That’s the day after tomorrow! There’s an unusually good roster this year, and I don’t just say that because I helped find speakers for it this year.

We’ve already had a preview event with a couple of great talks, including a real star, Jon Perry, who created two of the best games in UFO 50, Mini & Max and Party House. While I spent a lot of time with Mini & Max uncovering its many secrets, it’s but a small fraction of the time I’ve played Party House. (If you want to hear Jon Perry’s talk, from September, you can find it here, as well as Ezra Stanton’s talk on Synergy Networks in roguelikes, and Alexei Pepers’ Designing for System Suspense.)

I’ve already gushed voluminously about Party House here. Let’s move on to this year’s talk schedule. Times given here are Eastern/Pacific/GMT. (The later times in GMT are pushed into the following day.)

Saturday, October 25th

| Time | Speaker | Talk |

| 12:30 PM 9:30 AM 6:30 PM | Michael Brough | The Roots of Roguelikes in Fantasy Fiction |

| 1 PM 10 AM 7 PM | Sébastien “deepnight” Benard | Mixing Hand-Crafted Content with Procgen to Achieve Quality |

| 1:30 PM 10:30 AM 7:30 PM | Max Sahin | Stuff: The Behavioral Science of Inventory |

| 1:45 PM 10:45 AM 7:45 PM | Florence Smith Nicholls | Roll for Reminiscence: Procedural Keepsake Games |

| 2:30 PM 11:30 AM 8:30 PM | Alexander Birke and Sofie Kjær Schmidt | Hoist the Colours! Art Direction and Tech Art in Sea Of Rifts, A Naval Story Generation RPG |

| 3 PM Noon 9 PM | bleeptrack | From Code to Craft: Procedural Generation for the Physical World |

| 3:30 PM 12:30 PM 9:30 PM | Zeno Rogue | The Best Genre for a Non-Euclidean game |

| 4:30 PM 1:30 PM 10:30 PM | Cole Wehrle | Play as Procedural Generation: Oath as a Roguelike Strategy Game |

| 5 PM 2 PM 11 PM | Jeff Lait | Teaching Long Term Consequences in Games |

| 6 PM 3 PM Midnight | Ray | A Mythopoetic Interface Reading of Caves of Qud |

| 6:15 PM 3:15 PM 12:15 AM | Johnathan Pagnutti | Wait, No, Hear Me Out: Simulating Encounter AI in Slay the Spire with SQL |

| 6:30 PM 3:30 PM 12:30 AM | Jamie Brew | Robot Karaoke Goes Electric |

| 7:30 PM 4:30 PM 1:30 AM | Stephen G. Ware | Planning and Replanning Structured Adaptive Stories: 25 Years of History |

| 8 PM 5 PM 2 AM | Tyriq Plummer | Scrubbin’ Trubble: The Journey to Multiplayer Roguelikery |

| 8:15 PM 5:15 PM 2:15 AM | Andrew Doull | Roguelike Radio 2011-Present |

Sunday, October 26th

| Time | Speaker | Talk |

| 12:45 PM 9:45 AM 6:45 PM | Ada Null | Dyke Sex and Ennui: Generating Unending Narrative in “Kiss Garden” |

| 1 PM 10 AM 7 PM | Younès Rabii | We Are Maxwell’s Demons: The Thermodynamics of Procedural Generators |

| 1:30 PM 10:30 AM 7:30 PM | Dennis Greger | The Procedurality of Reality TV Design – An Overview |

| 4:15 PM 1:15 PM 10:15 PM | Paul Dean | Picking up the Pieces: Building Story in a Roguelike World |

| 4:45 PM 1:45 PM 10:45 PM | Patrick Belanger and Jackson Wagner | Hand-Crafted Randomness: Storytelling in Wildermyth’s Proc-Gen World |

| 5:15 PM 2:15 PM 11:15 PM | Nifflas | Music algorithm showcase |

| 6:15 PM 3:15 PM 12:15 AM | Seth Cooper | Building a Roguelike with a Tile Rewrite Language |

| 6:30 PM 3:30 PM 12:30 AM | Quinten Konyn | Anatomy of a Morgue File |

| 6:45 PM 3:45 PM 12:45 AM | Alexander King | Don’t Pick Just One: Set-Based Card Mechanics in Roguelike-Deckbuilders |

| 7 PM 4 PM 1 AM | Brian Cronin | Playtesting Process for Ultra Small Teams |

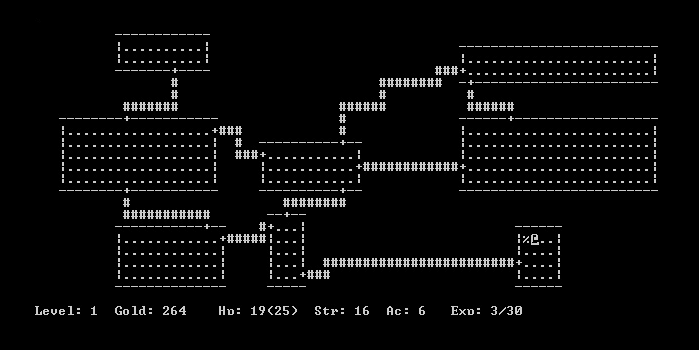

| 8 PM 5 PM 2 AM | Mark Gritter | Sol LeWitt, Combinatorial Enumeration, and Rogue |

| 8:15 PM 5:15 PM 2:15 AM | Dan DiIorio | Luck be a Landlord – 10 Lessons Learned |

| 8:45 PM 5:45 PM 2:45 AM | Liza Knipscher | The Form and Function of Weird Li’l Guys: Procedural Organism Generation in a Simulated Ecosystem |

If some of these talks seem like they’re spaced closely together, some of them are “lightning talks,” very short. Those have their titles in italics in the above list.

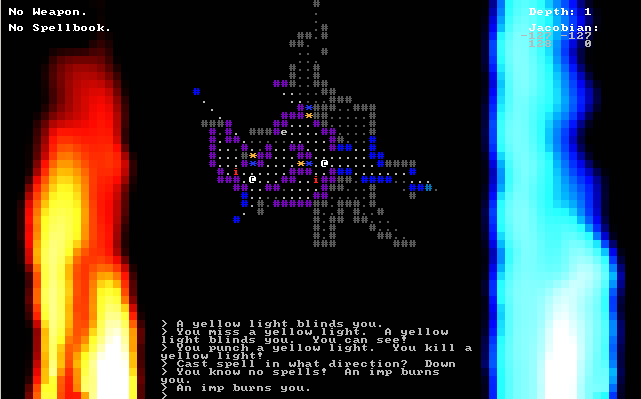

If you follow indie gaming circles, there are a fair number of exciting speakers among the talks! Jeff Lait (homepage) has made twenty highly interesting roguelikes, many as 7DRLs. Nifflas of course is the creator of Within a Deep Forest, the Knytt games, Affordable Space Adventures and others. Dan DiIorio is the creator of the oft-mentioned (at least in my hearing) Luck be a Landlord, and Zeno Rogue makes the long-lived, and brain-bending, HyperRogue.

And make sure to have a look at the Redbubble and Steam links too! In this year’s Steam selection, MidBoss and Shattered Pixel Dungeon are already on sale.