A few days we linked to Cosmic Collapse, a Pico-8 Suika Game clone that, I claim, is better than the original, or its many many other clones. Its graphics are less cloying, its music is much better, its physics are livelier which adds a greater element of skill, and it has missiles awarded at different score levels that can be used to destroy individual planets.

Cosmic Collapse’s bin is slightly smaller than Suika Game’s, and to compensate a bit for that its “winning” “planet,” The Sun, is only the 10th item in the game, unlike of Suika Game’s Watermelon, which is the 11th of its orbular objects. Nether game really ends at that point, it’s the kind of game that continues until you lose, but it serves as a thematic success point.

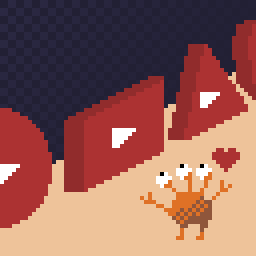

But as it turns out, as revealed by a comment by creator Johan Peltz on its itch.io page, Cosmic Collapse has two levels beyond sun. The first is a rather striking animated Black Hole object! After a lot of playing I finally managed to get to it. Here is a screenshot:

Pretty neat! The comment from the game’s creator mentions that there is a level past it, but that they don’t think it’s possible to reach. I don’t think it is either: to get to the Black Hole you have to have two Suns, and to get to that you have to have one Sun plus one Jupiter, Saturn, Neptune, Uranus, Earth, Mars, Mercury and Pluto. (I think it’s Pluto. What would it be if it wasn’t Pluto? Ceres?)

So, to get to the last object, you’d have to have a Black Hole plus a Sun, Jupiter, Saturn, Neptune, Uranus, Earth, Mars, Mercury and assumed-Pluto, which probably won’t all fit in one bin. My guess is it’s a guest appearance by some galaxy or something. Maybe someone can look at the game’s resources and find out what.

In addition to playing to get to Sun/Black Hole/Whatever Follows, it’s also possible to play Cosmic Collapse for score. The best way I’ve found to do that is to use missiles to destroy the largest objects when it becomes evident that you can’t do anything more with them. My highest score is nearly 15K. Indefinite play doesn’t seem quite possible, as missile awards come less frequently at higher scores, but it’s still fun to see how high one can get. (That’s not meant as a drug-inspired euphemism. Or a Donkey Kong-inspired one, either.)

Addendum: After writing this, I managed to get to Black Hole again, and got video of what it looks like in motion, which is pretty cool: