We love it when we find weird and unique indie games to tell you all about! Our alien friends to the left herald these occasions.

It’s another of those games that’s remade in Pico8, and in the process becomes subtly different, not necessarily better, but not worse either. It’s Make-Ten, and it’s free on itch.io.

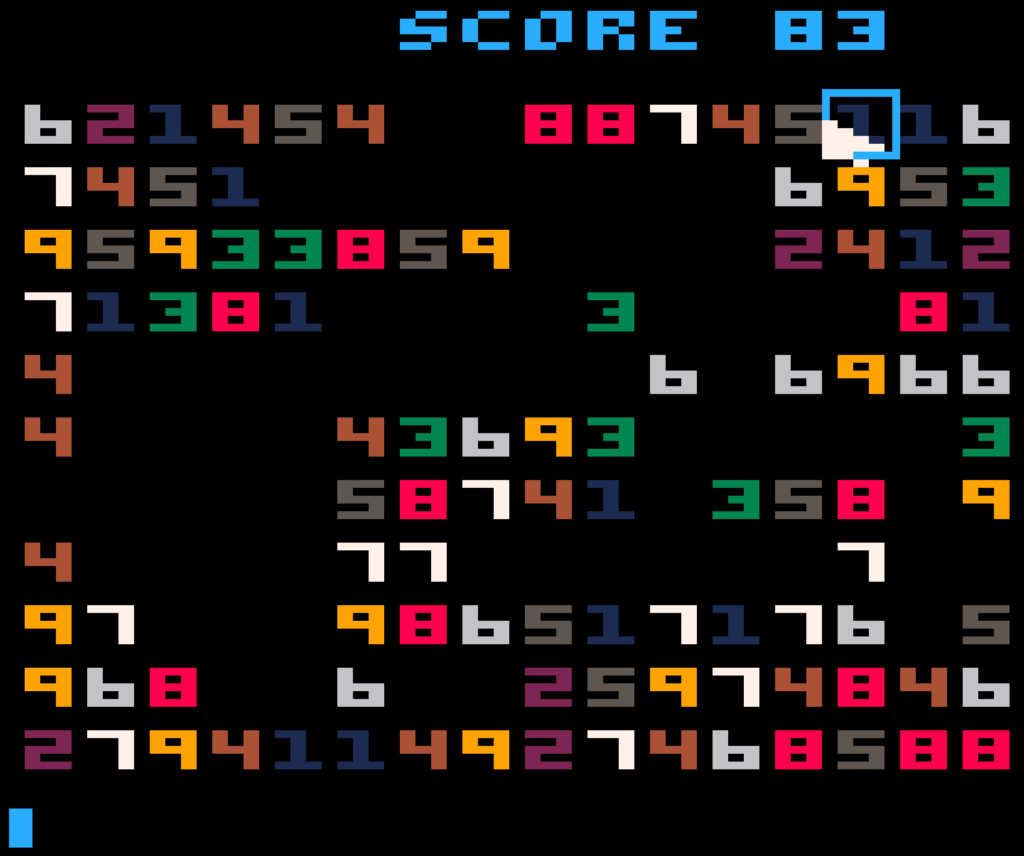

This time it’s not an arcade game. The remake is of a mobile and web game called Fruit Box. I’ve only tried the web version and, in this case, I think the Pico8 version is better. The UI is a lot easier to use for its only action, drawing boxes around numbers. The original uses a generic rectangular box, while the Pico8 version snaps the lines to the number grid, which works much better for me. Also the numbers are colored according to value, which helps readability a lot.

I’m sorry, I should explain what I’m talking about!

It’s one of those simple yet addicting games. You’re given a random field of digits from 1 to 9. You’re given a couple of minutes to draw rectangles around sets of numbers that up to 10. When you do, you get one point per digit you remove (which is a difference from the original), and those digits disappear from the board.

Obviously, pairs of numbers that add up to 10 are relatively easy to find. Any pair of 5s, for instance, can be immediately cleared. Each game usually starts with clearing away any quick pairs. Removed pairs make space to connect further digits. Empty spaces have no number value, and make it easier to clear more than two numbers at once. Some examples of common larger sets to surround (of course they can be in any order): 4-3-3, 1-2-3-4, 7-1-2, 5-3-2, 6-2-2 and 4-4-2. The tricky part is connecting two numbers in the corners of a box, when other digits get in the way, adding unwanted values to the sum.

The most valuable digit is 1, since they fit into the most possible combinations.

While Make-Ten is not a game for perfectionists, as it’s probable that most fields cannot be fully cleared, the game does let you keep playing after time concludes, which is an advantage it has over Fruit Box. It doesn’t count points after the time bar runs out, but it can be interesting to see how much of the board you can complete.

Make-Ten is really simple and has very little fuss about it. It plays quickly, and then it’s over. It’s a nice game for quick sessions. It was written in 500 characters of code, and doesn’t offer any progression or metagame. After two minutes, which begin the moment the game starts, there isn’t even a prompt to play again. To have another go, press Enter and choose to Reset Cart, or just close the window if you’re done.

Make-Ten (itch.io, by pancelor, $0)