Nicole Express is so knowledgable. How many blog posts have you seen about an obscure hardware issue, itself with obscure hardware, and the Japanese version of one specific cult game? Which the writer tested herself with her own unit and cartridge? Then went in to investigate herself with a freaking multimeter? Whaaa?

I won’t keep you waiting for the link: here it is. And here is my grossly simplified summary, intended to inspire you to go to the original article, if you have the time, and get all the deets.

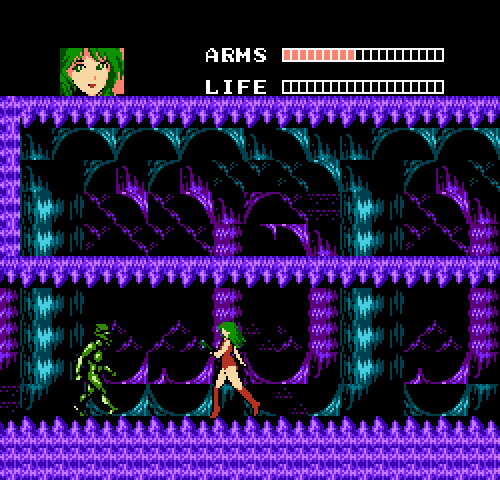

Guardic Gaiden, known in the US as The Guardian Legend, uses a weird trick to put its status bar at the bottom of the screen, instead of, as usually seen in an UNROM game, at the top. To create a fixed status window requires stopping whatever the processor is doing at a very precise time while the display is being drawn to the TV, and then changing some PPU registers to display the status.

More complex and versatile mappers, like the MMC family, have the ability to trigger interrupts at specific screen lines, but Guardic Gaiden/Guardian Legend doesn’t use an MMC. It doesn’t even have a raster line counter, so the game simply doesn’t know where on screen the raster beam is drawing.

There are still lots of games on the system that have status windows, even with MMC chips. The PPU has a built-in feature called Sprite 0 Hit, where the chip can signal when Sprite 0 (of the system’s 64 sprites) is being drawn on top of non-transparent background data. So what older games commonly do is put Sprite 0 in an unobtrusive place at the bottom of the status window at the top of the screen. When the Sprite 0 Hit register indicates a collision, the code knows it’s time to set up the PPU to display the main portion of the game screen.

There is a really big problem with this setup, though. Sprite 0 Hit doesn’t trigger an interrupt. It doesn’t stop the code to let it switch the graphics. It’s not even proper to say it “sends a signal.” It’s up to the code to check if Sprite 0 Hit has been triggered. If it has, then it’s time to set the scroll register to the right place, and maybe switch to the proper background tileset, and do whatever else needs to happen, and the code can then be off to run essential game logic, the actual game part of the game.

If it hasn’t… then, the code has to check again, and immediately. And if it hasn’t triggered then, to do it again. It has to literally check as quickly as it can, because if it delays in its check, the game screen might not get set up at the right moment, which will be perceptible as the bar straying down one extra line that one frame. Not the end of the world, but it looks glitchy. And this code will be running every frame, so if it strays down once, it might do it again, which is a more perceptible glitchiness.

Sprite 0 is set to trigger its hit at the top of the screen, because the code won’t have to spin its wheels checking the hit over and over. It wastes time, but not that much. This is why UNROM games put their status lines, with the score, timer, health bar and life counters, at the top of the screen.

Well, The Guardian Legend is an UNROM game, and maybe because creators Compile wanted to show off, they decided they’d put the bar at the bottom of the screen. And yet, their game doesn’t waste most of each frame just in maintaining the status bar.

How? And what does that have to do with the Twin Famicom? For that I’m going to direct you to Nicole Express’ blog post. May you find it as fascinating as I did!

Nicole Express: Is the Twin Famicom Flawed? The Case of Guardic Gaiden