And we’re off! Let’s start 2026 off with Flandrew’s look at the weirdest Star Wars game, the Famicom-only one Namco made. (11 minutes) It’s kind of a meme at this point, but gosh it’s even weirder than the Star Wars Holiday Special.

Tag: namco

Great Mappy Strategy Video

Our retro arcade strategy week is over, but this is a related video that I’ve been sitting on for quite a while. The Disconnector made a very nice strategy video (20 minutes) for Namco’s cult favorite cat-and-mouse game Mappy. It works as both an introduction and a guide to the game as it develops.

Not only is the information good, but it’s really well put together! Looking through the rest of their channel, while the post about other games (most recently about Robotron [8 minutes]) it seems to be the only strategy video of its sort. I hope they make more, I think they have a talent for it!

Adrian’s Digital Basement Uncovers Famicom Galaxian Cheat

Let’s get the link out of the way right off (27 minutes).

Famicom Galaxian, never released in the US until Namco Museum Archives Vol. 1, is a tiny program, even by Famicom/NES standards. It may be the smallest Famicom game; the ROM is only 16K large, taking up just half of the addressable cartridge space.

But even such a little program can hide secrets. Adrian found a multicart with an alternate version of Famicom Galaxian with rapid autofire, and that he preferred to play that than the official one.

And I don’t blame him! Galaxian nowadays, whether a port of the arcade original, is a slow and clunky thing to suffer through, but even back then there were some people who scratched their heads at its popularity. One of them was Craig Kubey, author of the classic-era arcade book The Winner’s Guide to Video Games, who called it the Worst Popular Game. But these problems evaporate if you can just hold down the button and annihilate the aliens, like you were playing Centipede.

Namco must have realized how much better the game would play with more shots, as they made your ship in Galaxian’s successor Galaga fire faster, and can have two shots on-screen at once. four with the double ship. Maybe as a result, Galaga is a lot more fun to play, even today.

Adrian got to wondering about that alternate version, called “Galaxians” in the pirate cart’s menu. He found a ROM image of it online and had a look at its code in Mesen’s code analysis tools and found the first thing the “classic” version of the game on the cart does is write a zero to a specific address in zero page. This, as it turns out, is to ensure a secret cheat is disabled. If a one is written there instead, it produces behavior exactly like the rapid-fire version, which in addition to being able to fire much more quickly recolors the logo on the title screen red.

Is this a disabled cheat function on the original cartridge? Maybe, but maybe not. Adrian found another version of the Galaxian ROM online that doesn’t have the cheat function, disabled or no. It’s unknown if this is an alternate official release, or the only official release. Maybe the version on the pirate cart was hacked to put the code in, or maybe it’s an obscure unreleased version, or else maybe it’s the Famicom Disk System version?

Geez, the mysteries abound concerning this sucky little game! Find out about it yourself here:

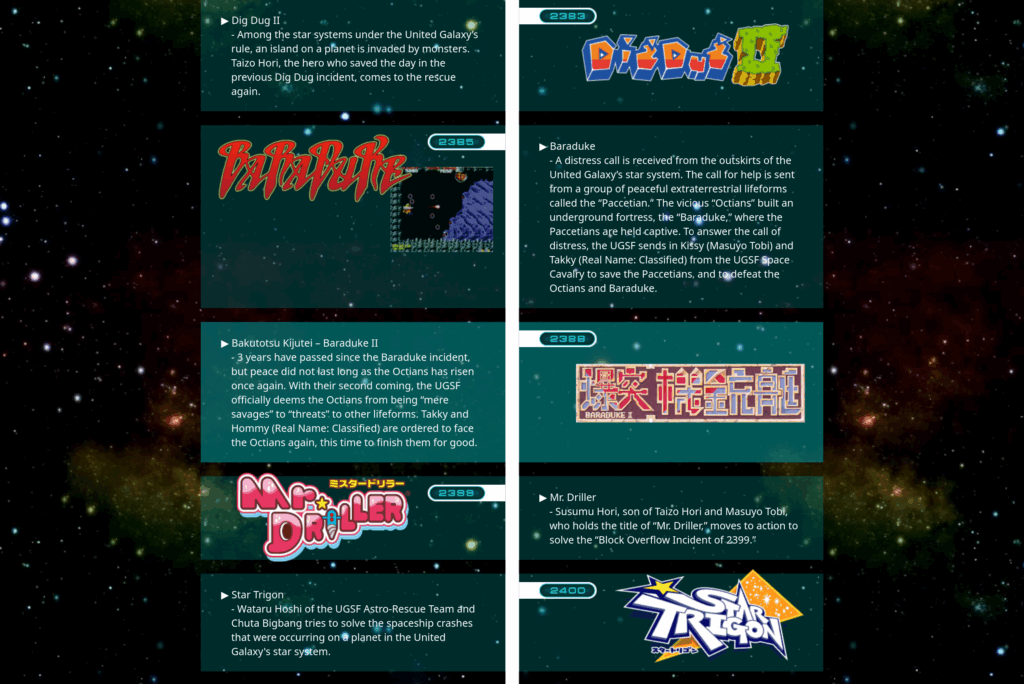

Again: All of Namco’s Space Sci-Fi Games Are in A Single Timeline

We’ve mentioned this before, but not only are all of Namco’s science fiction arcade games, which include Galaxian, Galaga, Baraduke, Bosconian, Starblade, Cybersled and many others, considered to be on a single timeline, but they even have a website dedicated to sorting and explaining it, ugsf-series.com! And it includes games you might not have pegged for it, like Dig Dug and Mr. Driller!

This even includes their upcoming “Shadow Labyrinth,” which I derisively describe as grimdark Pac-Man. Well, at least they’re serious about it!

Grouping Ghosts in Ms. Pac-Man

Ms. Pac-Man. Currently on the outs with Pac-Man rights-owner Bandai-Namco because its origins weren’t with them, and its developer GCC licensed the rights to another party than them, which has given us such travesties as “Pac-Mom.” Which is a shame, because in general Ms. Pac-Man is a better game than Pac-Man. Its four mazes don’t have the nuance that Pac-Man’s does (there’s no one-way routes, for instance), it doesn’t have scatter periods to give the player a breather during each board, and after board #7 its fruit, and the score award for chasing it down, is random, taking an important measure of skill and just throwing it up in the air and shrugging.

But it does have multiple mazes. And its Red and Pink ghosts behave randomly for the first bit of each board (here’s a prior post about that), eliminating the major design flaw of Pac-Man: its vulnerability to patterns. Pac-Man is certainly not the only game to lack substantive randomness, but the nature of its maze-based play is that it’s relatively easy to perform them. So long as you hold in the direction you need to go at least five frames before you reach an intersection, you can be sure that you’re performing a pattern perfectly, making Pac-Man into an endurance game more than anything. Ms. Pac-Man doesn’t have that problem.

But that doesn’t mean that Ms. Pac-Man can’t be mastered, and the basis of that is through a technique called grouping. Grouping can be done in Pac-Man too, but if you know some good patterns it isn’t necessary. But in Ms. Pac-Man it’s a key skill, both to make sure you eat as many ghosts as possible in the early and mid boards, and for general survival, for a bunch of ghosts in one lump is much easier to avoid than a scattered mess of four separate ghosts.

David Manning’s introductory video on grouping ghosts in Ms. Pac-Man (20m) is ten years old, but it’s still an invaluable aid for players seeking to master that game.

The basic idea is to understand the ways to move in the maze so that pursuing ghosts take slightly different routes to reach you, so that leading ghosts are delayed just a bit, or trailing ghosts approach you slightly faster.

This time I’m going to leave the explanation to the video, but it’s interesting to think about, and to see if you can apply this information yourself.

Gamefinds: Pac-Man Superfast

Part of Youtube’s doomed-to-fail Playables series, so enjoy this before it gets heartlessly deleted by Google when they decide games on their video platform don’t make sense, isn’t worth it, or whenever Netflix gives up on games and they don’t feel they need to compete on that front anymore.

The game is basically Pac-Man, but with a Championship Edition-like speedup gimmick. As you eat dots, the game slowly increases the simulation rate. it never really gets up to CE’s white-hot speeds, but it does get pretty fast. You get a slight slowdown when you finish a board and lose a life. Since you start with five lives, earn an extra one every 5,000 points, and each of a rack’s three (instead of the arcade’s two) fruit are worth at least 1,000 points, and even more as you advance to later boards, you are unlikely to run out of lives. The game ends after 13 levels, so you have a decent chance of finishing this one!

My best score is right around 150,000 points, but I was only playing casually. See if you can do better!

Katamari Damacy Turns 20

Paste Magazine has a piece up on Namco’s seminal Playstation 2 game Katamari Damacy turning 20. It’s still one of those titles that has the power to attract attention when they see it played, especially if they’ve never heard of it before.

In case you haven’t heard of it (is that possible?)–you, playing the part of the Prince of all the Cosmos, have a sticky ball, called a katamari, which means “clump,” on a series levels that are laid out as kind of surreal versions of normal Earth environments. Typical places might include a Japanese living room, a modestly-sized town, and a larger city. The idea is to roll the ball so that it comes into contact with various objects. If they’re at most a certain size relative to that of the ball, they stick to it, and in so doing make its aggregate size a little larger. The more things that stick to the ball, the bigger it gets, and so the larger the size of things that will stick. If you reach a certain target size within the time limit you complete the stage. If you fail then the Prince’s father, the King of All Cosmos, expresses his disappointment in you in a ludicrously extreme manner. While not all of the levels are about achieving raw size, the most entertaining ones do, and they’re all about fulfilling certain goals with the katamari. This should give you a sense of how the game plays, if needed:

Since Katamari Damacy, designer Keita Takahashi hasn’t been idle. They also made the downloadable game Noby Noby Boy for PS3, worked on the Flash MMORPG Glitch, and made the weirdly wonderful Wattam. I’ve mentioned previously in these pages that I’m looking forward to his next project, To A T, presuming it survives the travails of publisher Annapurna Interactive.

Back to the Paste Magazine article, it mentions that the game happened due to a fortuitous set of events that involved a bunch of student artists looking for a project, and a number of programmers who worked on it so as not to be seen as idle in a time of layoffs. I personally remember that a substantial part of its legend, perhaps even the tipping point, was due to a particular review on Insert Credit by Tim Rogers. While it’s possible to see his review as a tad self-indulgent, I really don’t have any standing to criticize, seeing as how I created pixel art aliens to be our site’s voice. Hah.

It did the trick of making people consider the game though, which may have been how this very Japanese game got an English localization, rainbow-and-cow festooned cover intact. I was in college at the time, and for a few months they had PS2s to play in the student union. I found a certain delight in taking in my copy of Katamari Damacy (it had been released in the US by this point) and just playing through Make The Moon. It was the kind of game that would arrest other people in the room and cause them to just watch for a couple of minutes. Another time, I played it on the TV at my cousin’s house when there was a certain teenager, at the age where they sometimes get into a mood to dismiss everything. They scoffed at the game when I put it in; eight minutes later, they were calling out “get the giraffe!”

That Katamari Damacy could happened was a miracle; that it had, and continues to have, this effect on people, seems like magic. It isn’t perfect, because it doesn’t ever make sense to say a created work is “perfect,” there are always tradeoffs, but it is a care where it’s difficult to say it could be improved. Sure, it could be a little easier, but it still never takes more than a few attempts to pass a level. It could be a little harder, but that would make it much less accessible. Suffice to say that it’s at a local maxima of quality, and that can’t be an accident, it’s there because strong effort put it there.

It was inevitable that it would get sequels. Critical consensus is that the best of them was the first one, We Love Katamari, stylized on its logo with a heart in place of Love. It’s the only one with creator Keita Takahashi still at the helm. It’s a little less thematically together than the original; the premise is that the King of All Cosmos from the first game fulfills requests made by fans, much like how the game itself was made due to fan requests. Later sequels were made without Takahashi’s efforts. They feel increasingly fan-servicey, in the sense that they were trying harder and harder to give fans what they wanted, without being sure of what that was.

With each sequel, the luster dulled a bit. There was a furor over the third game in the main series, Beautiful Katamari on Xbox 360, for having paid DLC that was actually just unlock codes for levels that shipped on the disk. There were mobile sequels that were mostly terrible. The last of the series until recently was Katamari Forever, a name that proved inaccurate. More recently, remakes of the first two games have sold fairly well, so maybe it still has a chance to redeem itself with a proper successor.

Anyway, happy 20th birthday to Katamari Damacy. May it spend 25 more years of showing Playstation kids that gaming can be something more than Call of Duty and Fortnite.

What’s So Random About Ms. Pac-Man

I’m not going to say that famously Ms. Pac-Man is a more random game than Pac-Man, because who really knows things like that who isn’t a hardcore gamenerd. But among hardcore game nerds, it’s common knowledge. (If you didn’t know, A. congrats on your coolness, and B. sorry to now destroy your coolness.) Here a video about how randomness works in that game, from Retro Game Mechanics Explained (21 minutes):

Pac-Man is a game that is vulnerable to patterns: if you do exactly the same thing each time on the same level, the same results will occur. There is one pseudo-random element in Pac-Man though: when vulnerable ghosts reach an intersection, the code picks an arbitrary address from a range of memory addresses, then uses that value to pick a direction to decide which route to take. Two implications of this: vulnerable ghosts are most likely to head left at intersections and least likely to go up, and if any byte in that range changes the behavior of the game slightly changes too, even if it’s not an executable byte. Patterns still work in Pac-Man, despite this pseudo-random function, because the seed is reset at the start of every level, so if you do exactly the same thing, vulnerable ghosts will still have the same information fed to their movement routines.

Ms. Pac-Man has other sources of randomness: the ghosts, in Scatter mode, use a different source of pseudo-randomness to decide where to go, one that isn’t so easy to manipulate; and which fruit appears and which of four predefined routes (three for one of the mazes) it’ll take through the board.

Ms. Pac-Man doesn’t have its ghosts scatter periodically through the level like they do in Pac-Man. They only scatter at the start of the board. It’s not much randomness, but it’s enough to upset rote pattern creation, since each ghost has the opportunity to make several decisions of which path to take during that period. The way the randomness is handled is interest itself. The ghosts pick one of the corners of the board, much like they would in original Pac-Man, but randomly, when making their choice of target to home in on.

So there! Now you can amaze your friends, if it were 40 years ago and your friends were then able to be impressed by your knowledge of Ms. Pac-Man! You’re retroactively welcome!

Random Elements of Ms. Pac-Man (Retro Game Mechanics Explained on youtube, 21 minutes)

Wherefore Pac-Man’s Split Screen?

I did a search of the blog to make sure I haven’t posted this before. I’m really an obsessive tagger, and it didn’t show up under the tag pacman, so I think it hasn’t been seen here before. Let’s fix that now!

It’s a video from Retro Game Mechanics Explained from six years ago, and it’s 11 1/2 minutes:

Here’s a terse summary of the explanation, that leaves out a lot. Like a lot of 8-bit games (the arcade version uses a Z80 processor), Pac-Man stores the score in one byte, making the maximum it can count to 255. Since it doesn’t use signed arithmetic, it doesn’t use the high bit to signify a minus sign and so flip to negative at 128.

As an optimization, Pac-Man’s code uses the depiction of the maze in the video memory, itself, in the movement of both Pac-Man and the ghosts. If a spot has a maze wall tile, then Pac-Man can’t go there, and the ghosts won’t consider that direction when moving.

At the start of every level, the game performs some setup tasks. It draws the maze anew, including dots, Energizers and walls. One of these tasks is to update the fruit display in the bottom-right corner. It was a common design idiom at some arcade manufacturers, especially at Namco, at the time to depict the level number with icons in some way. Galaga shows rank insignia in the corner; Mappy has small and large balloons and mansions.

Pac-Man’s code shows the bonus fruit for each level, up to seven of them. If you finish more than seven levels, only the most recent seven are shown. If you get far enough eventually this will be just a line of Keys, the final “fruit.”

The code draws them from right to left. There’s three cases (the video goes into much more detail), but generally it starts from the fruit of six minus the current round number, draws it, counts up once and moves left two tiles, draws that one, and so on.

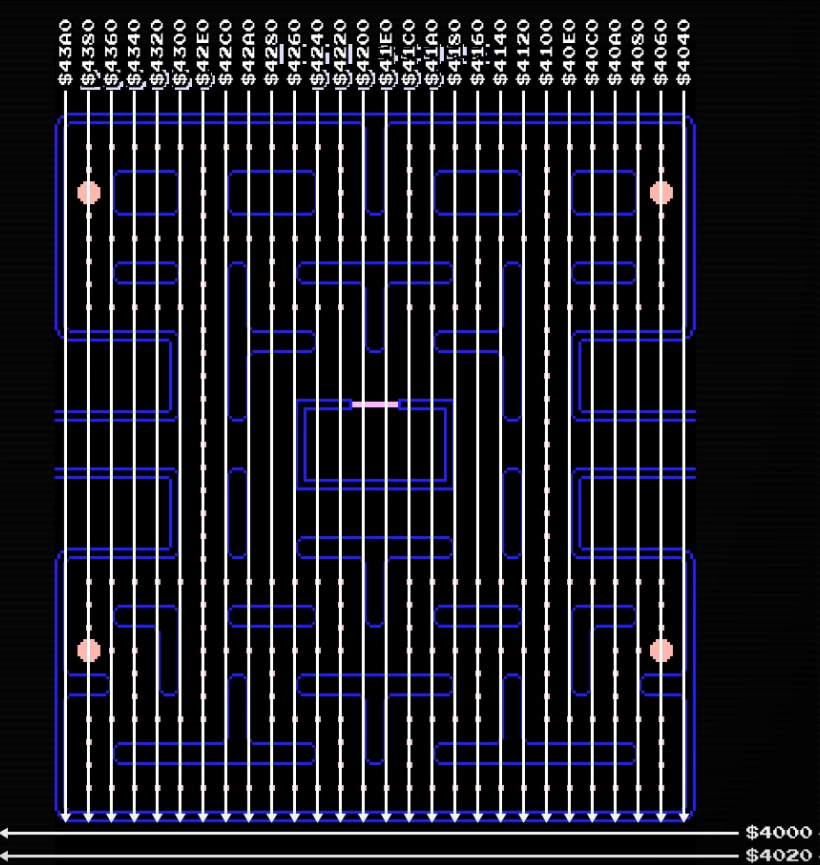

An interesting fact about Pac-Man’s graphics hardware is that the screen doesn’t map as you might expect to the screen! A lot of arcade games have weird screen mappings. Most consumer programmable hardware will map characters horizontally first vertically second, like a typewriter*.

In Pac-Man, the bottom area of the screen comes first in memory, starting at memory location hex $4000 (16384 decimal), and it doesn’t go forward like an English typewriter, but is mapped right to left. The first row of 32 tiles comes at $4000, and the second row is $4020. Then the playfield area is mapped completely differently, in vertical rows going down starting from the top-right of its region, then the next vertical row is the one to the left of that, and so forth to the left edge of the playfield. Then comes the score area at the top of the screen, which are two final rows mapped the same way as the bottom area, right to left.

When Pac-Man’s score counter overflows, it breaks the check for the limit for only drawing seven fruit, and causes it to draw 256 fruit. This is why the tops of keys are drawn beneath the upper-halves of the fruit at the bottom of the split screen. It also breaks the tile lookup for the fruit.

As it continues writing its missourced fruit tiles in memory, it goes back in memory each time to draw the next fruit, and after the fruit section of the display it keeps going to the left, into the area where Pac-Man’s lives are displayed, then it keeps going and overwrites half of the maze tiles. Then Pac-Man’s lives (and any empty spaces that indicate the lack of lives) are plotted, overwriting fruit after the first ones drawn and obscuring some of the memory corruption.

Since the game’s actors use that data to decide where to move, and where dots and Energizers are placed, it means they can move outside the bounds of the maze, and that there won’t be enough dots for Pac-Man to eat to complete the level. That’s what makes it a kill screen: if Pac-Man loses a life, a few dots will get placed in the maze as the fruit are redrawn, but it’s not enough to bring the dot-eaten count to 244, which triggers the level clear function.

If the fruit-drawing loop didn’t stop at 256 (another artifact of using 8-bit math for the loop), it’d go on to clobber the rest of the maze, the score area at the top of the screen, then color memory (which has already been clobbered by the palette-drawing portion of the loop). Then, going by a memory map of the arcade hardware, it’d hit the game logic RAM storage, which would probably crash the game, triggering the watchdog and resetting the machine.

The visual effect of the split screen is certainly distinctive, enough that since Bandai-Namco has capitalized on its appearance at least once, in the mobile (and Steam and consoles) game Pac-Man 256. I’ve played Pac-Man 256: it’s okay, but, eh. It’s really too F2P unlocky.

* Yes, I just used a typewriter’s operation as a metaphor for something a computer does. It didn’t feel acceptable to use another computer thing as the comparison, since ultimately the reason they do it that way is because typewriters did it that way too. I guess the fact that it’s English reading order would be better to use, but I’m really overthinking it at this point.

Sundry Sunday: Waluigi Sings “Rainbow Connection”

Sundry Sunday is our weekly feature of fun gaming culture finds and videos, from across the years and even decades.

It’s Waluigi, and he’s singing “Rainbow Connection.” You need more? Are you not entertained?

It’s from Matthew Tarando, aka. Bitfinity, the one who made the Brawl in the Family webcomic. It’s not the first of their works to make it to this site, and it probably won’t be the last.

The Muppet-like version of Waluigi is a highlight. He looks like Dr. Don from Point Blank, a.k.a. Gun Bullet! It feels like it’s come full circle, since Point Blank is essentially WarioWare with light guns!

1 Credit Clear of Tower of Druaga, With Explanations

This one I find rather fascinating. There may be no arcade game ever made as purposely frustrating to play as Namco’s Japanese-only game The Tower of Druaga.

Hero Gilgamesh (often shortened to “Gil”) must pass through 60 maze levels, collecting a key from each then passing through the door to the next, while defeating enemies that get in his way, in order to rescue his love Ki from the villainous Druaga.

BUT almost all the levels have a secret trick to perform. If this trick is accomplished, then a chest will appear that, if collected, will grant Gil a special ability. Some of these abilities are helpful. Some, in fact, are necessary, and if they aren’t collected then on some future level Gil will be unable to advance! The tricks are explained nowhere in the game: it just expects you to know them, if not discovered personally then learned through word of mouth. (This was like a decade before most people had access to the internet.)

What is more, nothing in the game explains what the treasures are or what they do, or what you’ll find on each level if you do know the trick. And a few of the treasures are actually harmful! It means that, to win, you have to rely on a host of hidden information, obtained by both your own observation and from what you’ve heard from others. Which requires a ton of quarters to get, which suited manufacturer Namco just fine. Unfortunately (or, maybe, fortunately?), the game crash prevented Namco from trying its luck with this game in Western territories.

As a result, The Tower of Druaga is a game that’s probably experienced watching someone else play, rather than playing yourself. That’s what this video is, Youtube user sylvie playing through the whole game, not just advancing through, but explaining how it’s done along the way. It’s an hour and three minutes long:

Sundry Sunday: Dig Dug Explained Stupidly

Sundry Sunday is our weekly feature of fun gaming culture finds and videos, from across the years and even decades.

It’s pretty short, at a minute and a half, but here is a brief and silly explanation of the classic arcade game Dig Dug. That’s all!