I turned fifty in February. No one believes me when I tell them my age, and for that reason I’m not too loud about it in person-one can very easily get tired of hearing “no way” in response to an admission like that. I don’t quite know what to make of my generally-youthful appearance. I know that things like that don’t last forever, so I’m trying to enjoy it without too much trepidation.

Anyway, fifty years in 2023 is a neat match for the history of commercial computer gaming. I was an early reader, so in the back of my brain I still remember hearing about the introduction of the Atari VCS, a.k.a. the 2600, in 1978, when I was but five. But there is a game system older than me: the Magnavox Odyssey.

The Odyssey was such a strange beast, in several ways. The first commercial TV-based home gaming computer, it didn’t have true interchangeable game cartridges; all of its games were hard-wired into the console. All of its cartridges came with the unit, and inserting a cart simply completed a circuit that told the internal electronics which game to run. The games had extremely simple graphics, we’re talking pre-Pong-level. Games cleverly used screen overlays, with translucent elements, to provide playfields and tracks. The computer didn’t even count score on-screen; it relied on players to keep track of that themselves.

The Magnavox was visible and remembered, moreso than really obscure machines like the Fairchild Channel-F and the Bally Astrocade, enough that it inspired a much more powerful (but still pretty weak) successor with true software called the Odyssey 2, or, as the machine’s trade dress stylized it, the Odyssey2. It’s funny: I have never once in my whole life ever heard anyone call it the Odyssey Squared.

Stories from the time tell us that the Magnavox Odyssey was stymied in the marketplace through an expectation, they say created by its advertising, that one could only use the Odyssey on a Magnavox TV. That wasn’t true, one didn’t need a Magnavox TV to use the Odyssey, but since a major component of each game had to be physically affixed to the screen, and its location and size had to match up with what the game’s design expected them to be, one did have to have the right size of TV to play properly.

The Odyssey was actually a little bit more of a success than commonly represented, surviving its first Christmas season without being discontinued, and even inspiring the production of some cheaper cut-down versions that only played some of the original’s games.

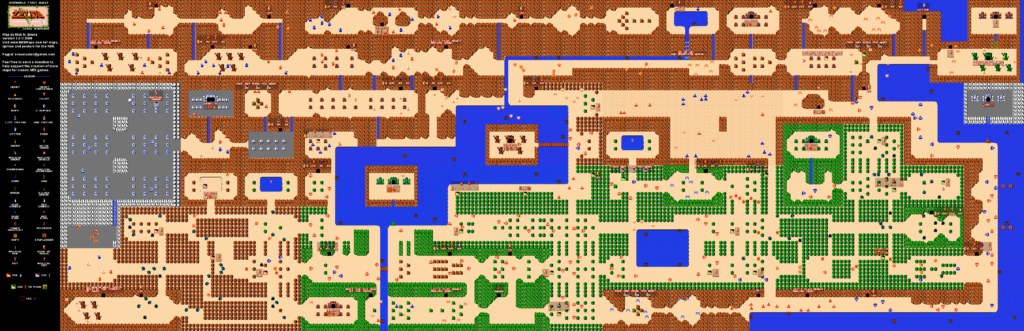

If you’re wondering how this worked out in practice, let’s take a look at Ski, one of the games that the Odyssey played. Here’s a page describing it, which links to its printed rules that came with the machine, and here’s video of two young people gamely trying it out:

Infamously, the patent that Magnavox owned on the Odyssey was used to terrorize the game industry for a while. According to an NPR obituary on Odyssey team leader Ralph Baer in 2014, Magnavox eventually garnered over $100 million on infringement lawsuits, far more than it ever earned in sales, up until the patent expired in the early 90s. Consider: a patent issued on a machine invented before I was born was used to attack game makers into the SNES era. And this wasn’t even a software patent, which I would hope everyone recognizes sucks by now: the Odyssey was a physical machine, and its patent was of the ordinary kind.

(Yeah, it’s 2023 and I’m still banging on about patents. I know there are legitimate uses for them. In some industries, unpatented inventions are ruthlessly copied by others. I’m not here to argue about them in general.)

To play Ski, the player uses the weird two-dial controller that came with the Odyssey, that worked kind of like the dials on an Etch-a-Sketch, to move a square on the screen. The square is the only visual element of the game: the whole rest of the screen is a black field. Over this, the player puts the Ski overlay, which depicts a simple course as a dashed line, winding around drawings of trees and mountains. The overlay is opaque except for the dashed line, so as the player moves the square with the controller, it lights up the line. The idea is to get the square from the start location to the end by one of several routes. The player is “penalized” for hitting obstacles only in the sense that they are left to apply their own penalties: participants are expected to be honest in this, maybe with the aid of a referee to do the time/score recording.

Magnavox developed a new version of Ski, called Ski Festival, that was planned to be released for a successor to the Odyssey, not the Odyssey 2 but a different successor that was cancelled. Little is known about it, other than an image in a sales brochure. People have zoomed in on the image and attempted to recreate the game from it. Video of this valiant attempt is here.

Both of the videos in this post come from the Odyssey Now project (Youtube) from the Vibrant Media Lab at the University of Pittsburgh, which seeks to preserve and provide information on this important console.