‘@Play‘ is a frequently-appearing column which discusses the history, present, and future of the roguelike dungeon exploring genre.

If you missed it, you might want to start with our brief narration of the beginning of Omega.

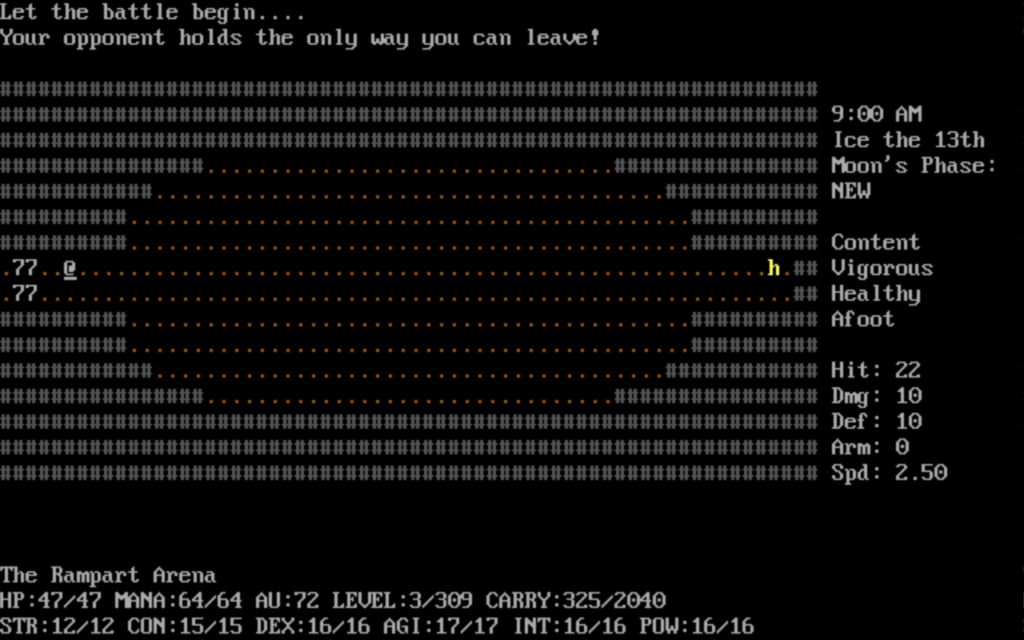

Omega is beloved of a small but devoted cadre of players. Like Alphaman, it is a prominent early roguelike with an overworld, but unlike Alphaman the world map is the same from game to game. In this it can be recognized as a predecessor of ADOM. It is probably the classic roguelike with the most detailed and interesting town, the well-named city of Rampart.

The CRPG Addict, whose Sisyphean project is to play, complete, and write about every CRPG ever made, reviewed Omega in the early going, although his victory over the game was the easiest kind of win (retirement), and he cheated by restoring save files. Although it must be said, Omega’s own help text itself suggests that players back up their saved files if they’re having trouble, and there are some things about it that almost make me want to play that way.

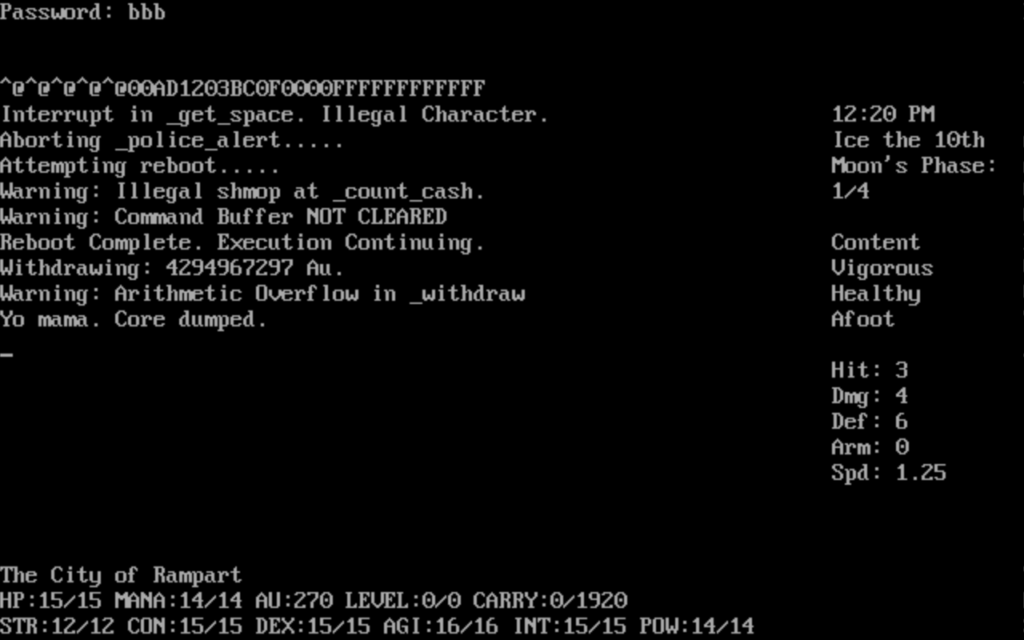

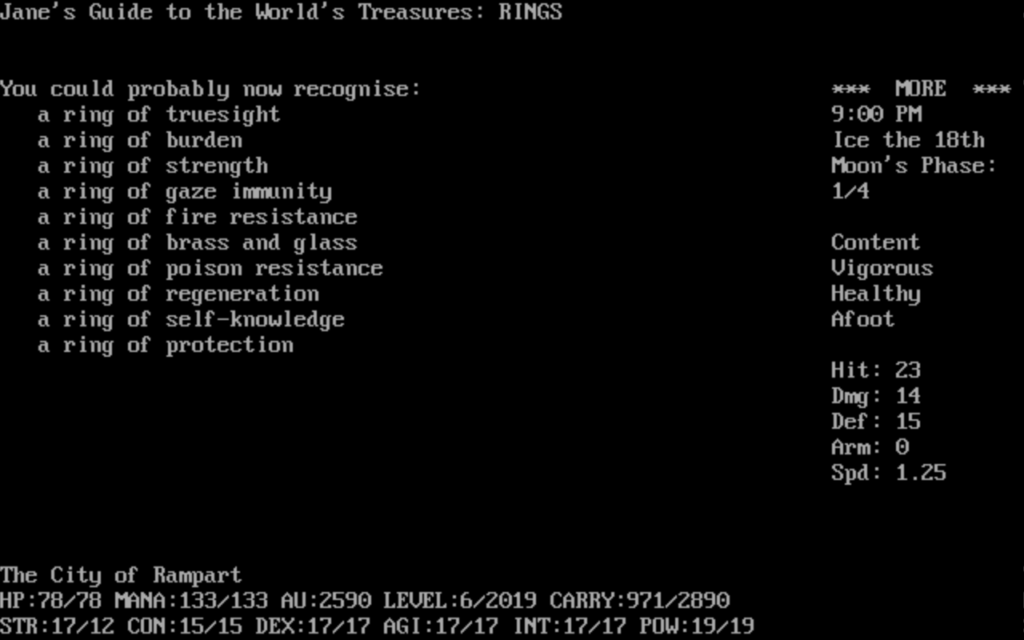

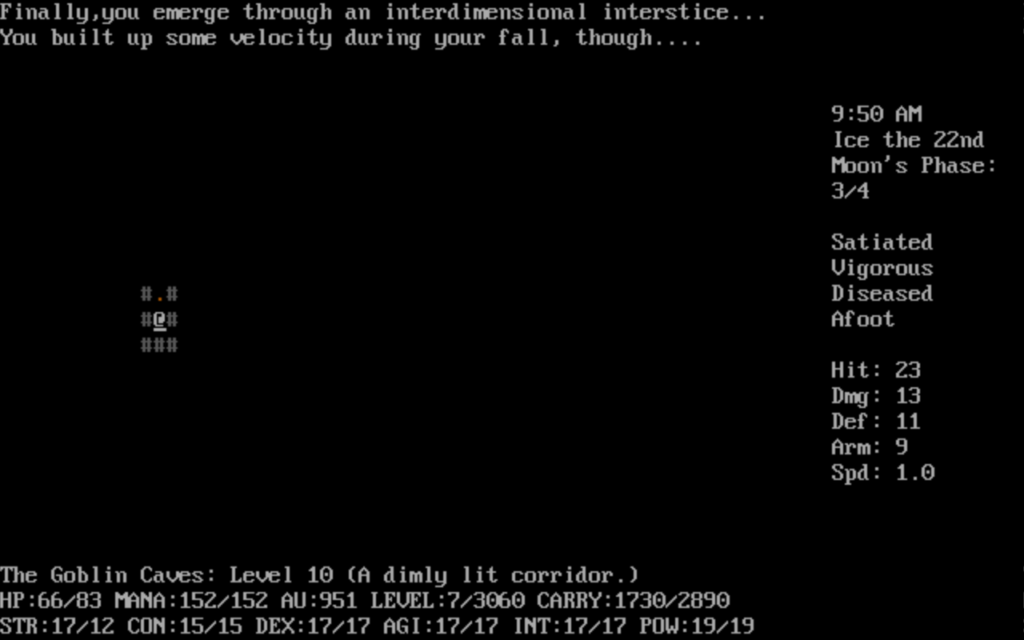

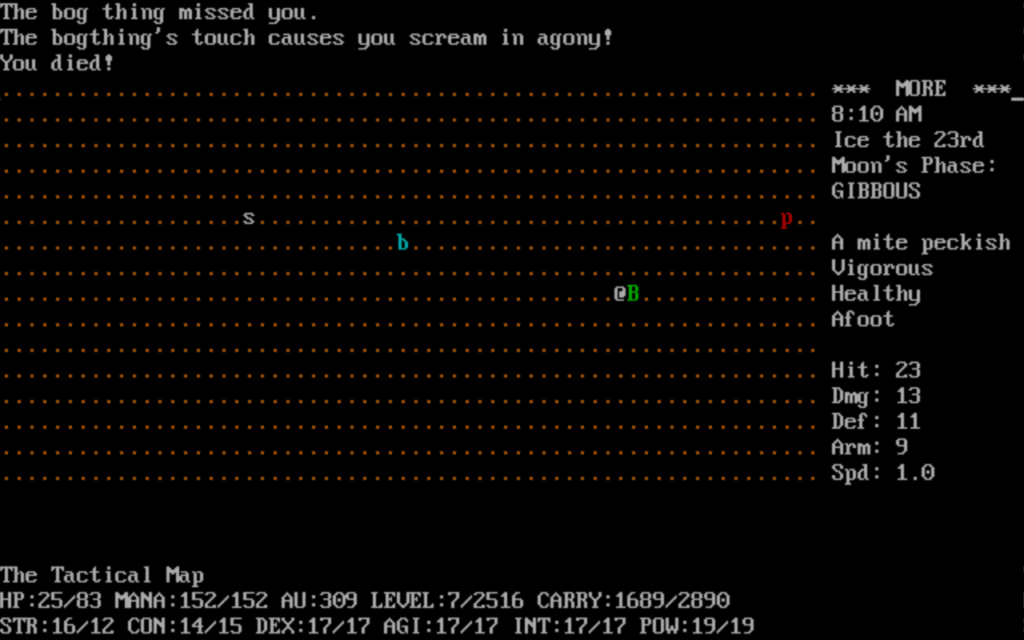

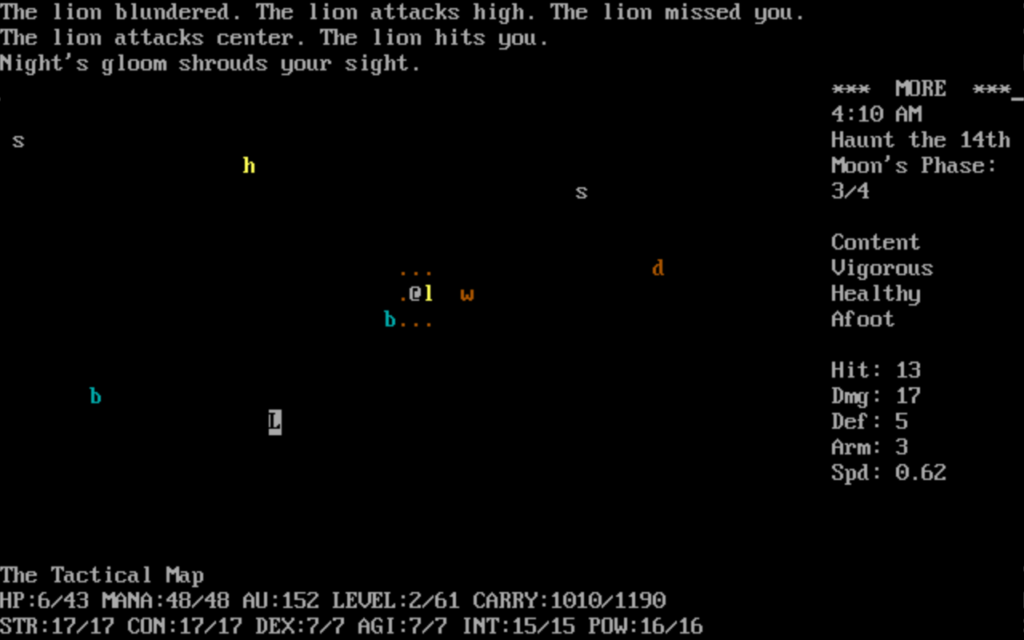

Omega’s sense of difficulty is a bit unusual. It is overflowing with random events, some of them you can’t do anything about, and it’s possible for those events to kill you with very little warning. But if a character can survive the early going, there are also non-random resources that a knowing player can take advantage of that can help them get a leg-up on the game. In this way it’s like NetHack, in that there are counters to randomness, and a bunch of necessary lore to discover that greatly enhances one’s chances of winning.

Much of this lore has been saved in FAQs, spoiler files, blog posts, and comment sections scattered throughout the internet. Most of these sources remain out there to find, but the nature of the web and the intervening years have made them harder to find than they once were. I’ll present a list of links you can use to find them later, but I’ll gather the most important early-game for you once we get into its gameplay.

Omega is a game that has entertained players for many years. In its heyday it was a popular topic of discussion on the Usenet group rec.games.roguelike.misc. But it does have a number of attributes that have fallen out of favor with players nowadays. I’m not even talking about the typical things one has to get used to in order to play most classic roguelikes. Omega has some particular things you’re probably just going to have to acclimate yourself to if you’re coming to it from contemporary types of computer gaming. This isn’t to seem overly critical; there are a lot of interesting adventures to be had in its world, but there is a bit of a learning curve. But let me give you a broad overview first.

About the Game

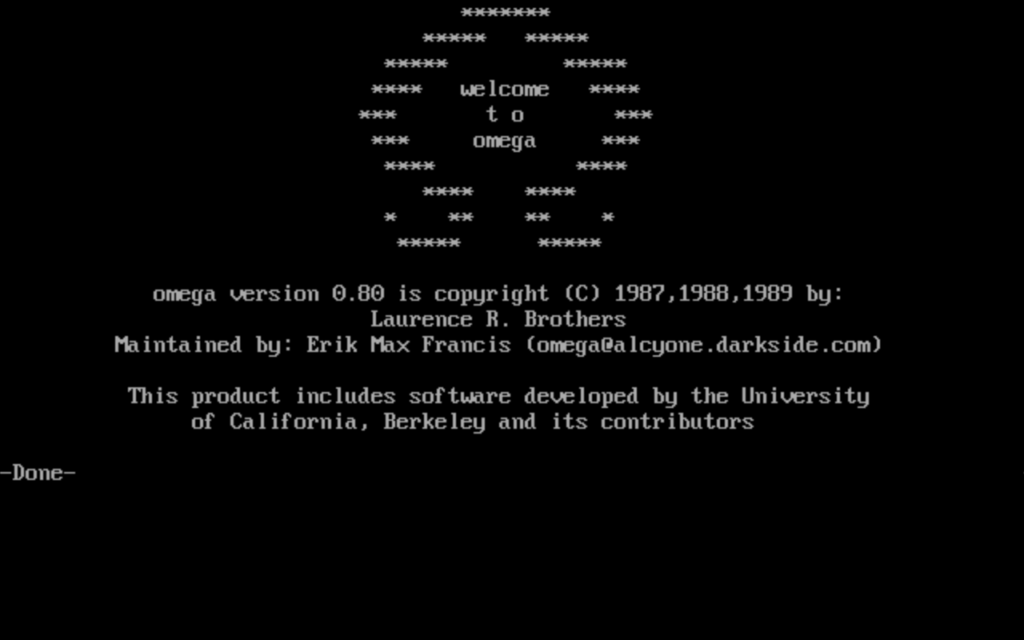

Omega’s origin is said to extend back to the late 80s, but records on the internet extend only as far back as about 1993. It was created by Laurence Raphael Brothers while he was at Rutgers University. He passed the torch to others to maintain the game at some time before 1993, but even version 0.90.4, the most recent version of the core code of Omega, lists his name in the source code as copyright holder. Lawrence Brothers has been known to sometimes get in contact with people who write about Omega, including the CRPG Addict.

In 1993 it seems Robert Paige Rendell picked up development of Omega. Erik Max Francis currently maintains the official Omega Distribution Page. While the core game has seen no development in a long time, ports for various systems have been made, including OS/2, classic MacOS and even a Windows port with graphical tiles.

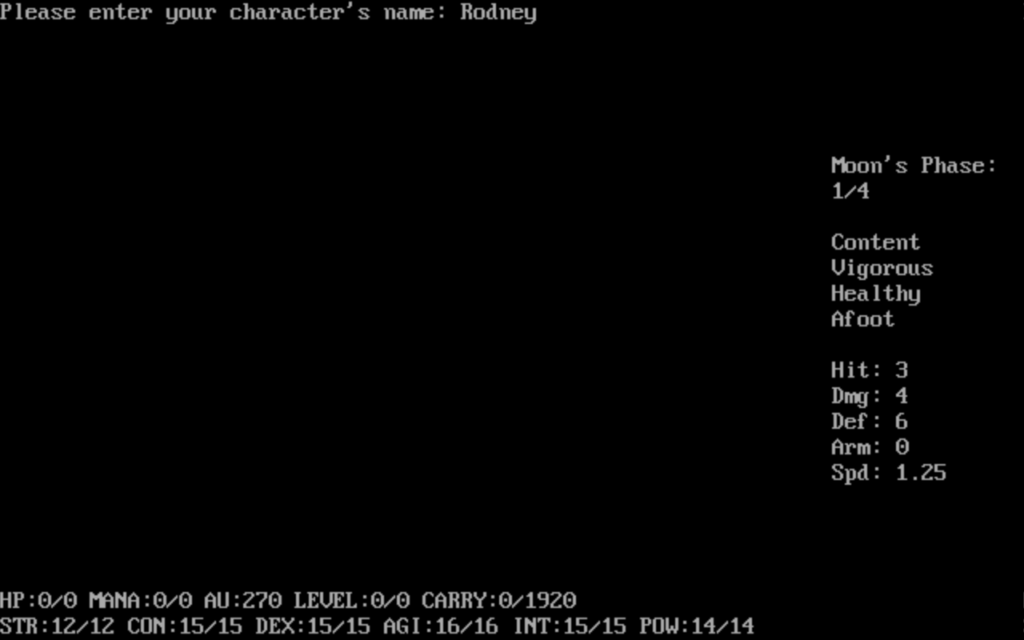

Omega doesn’t present you with a great scenario at the start of play. It is more like a general setting, in TTRPG terms a sandbox that you investigate on your own. Your explorations are mostly directionless at the start. There is a character you can turn to that can provide players with a direction for their explorations, and you can also get quests from the Duke of Rampart, but the game doesn’t point you in their direction, and nothing forces you to heed their words. Omega is more like an adventure setting than a single mission you are trying to perform.

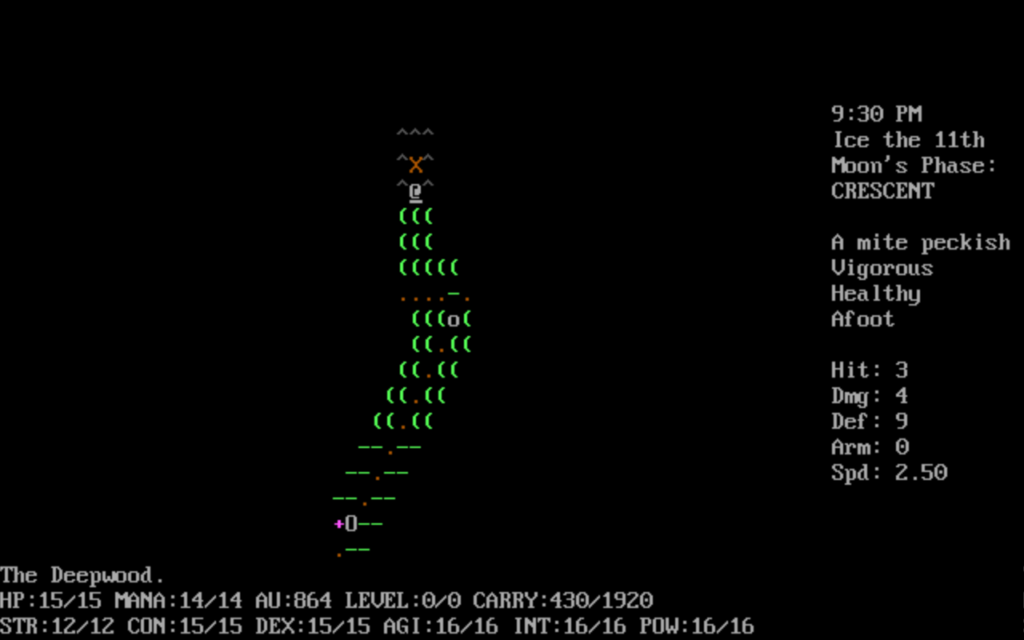

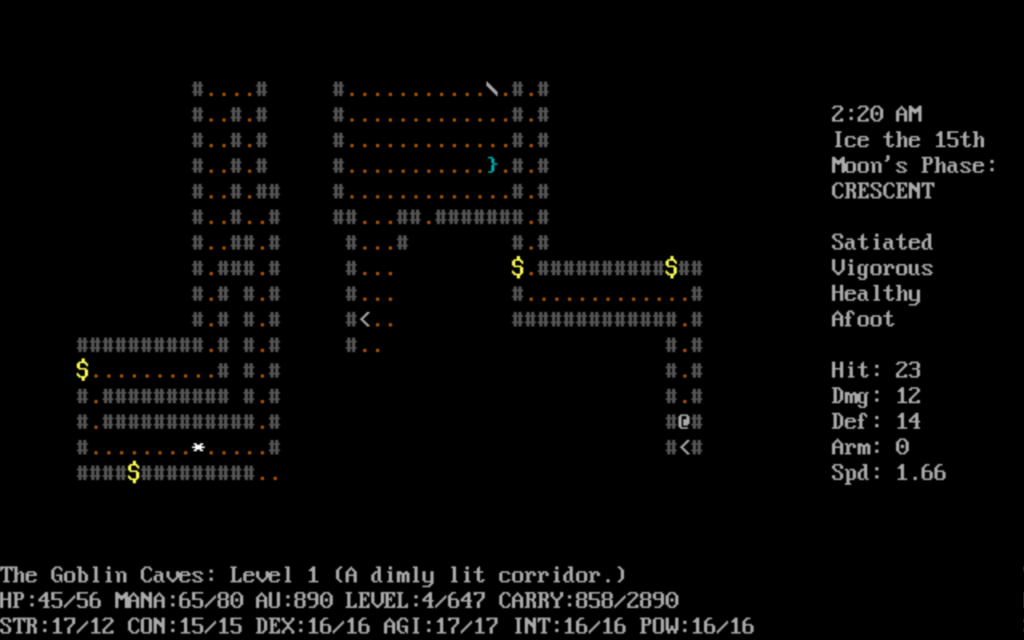

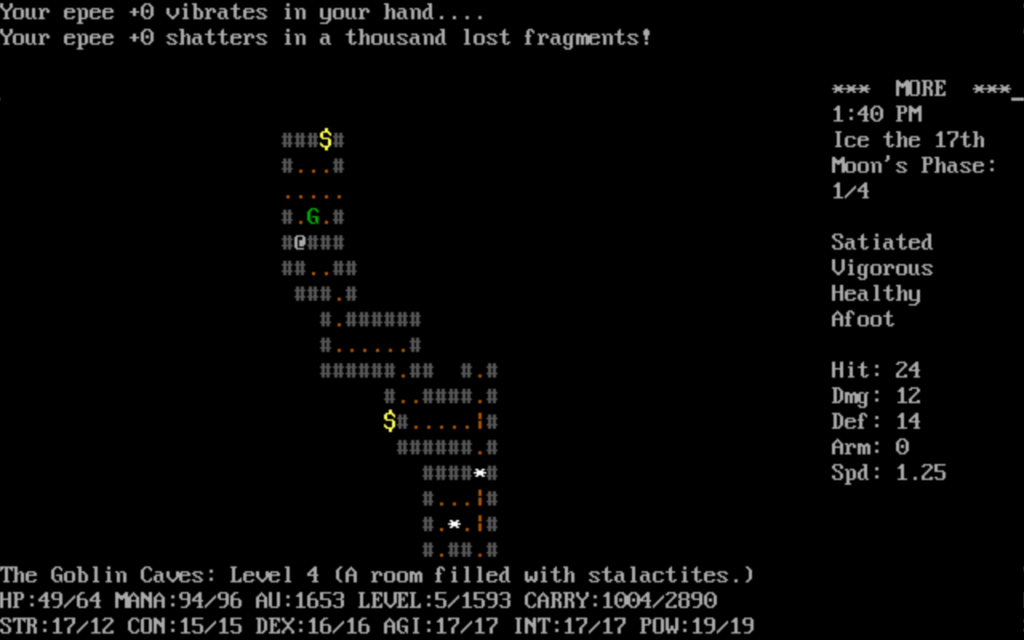

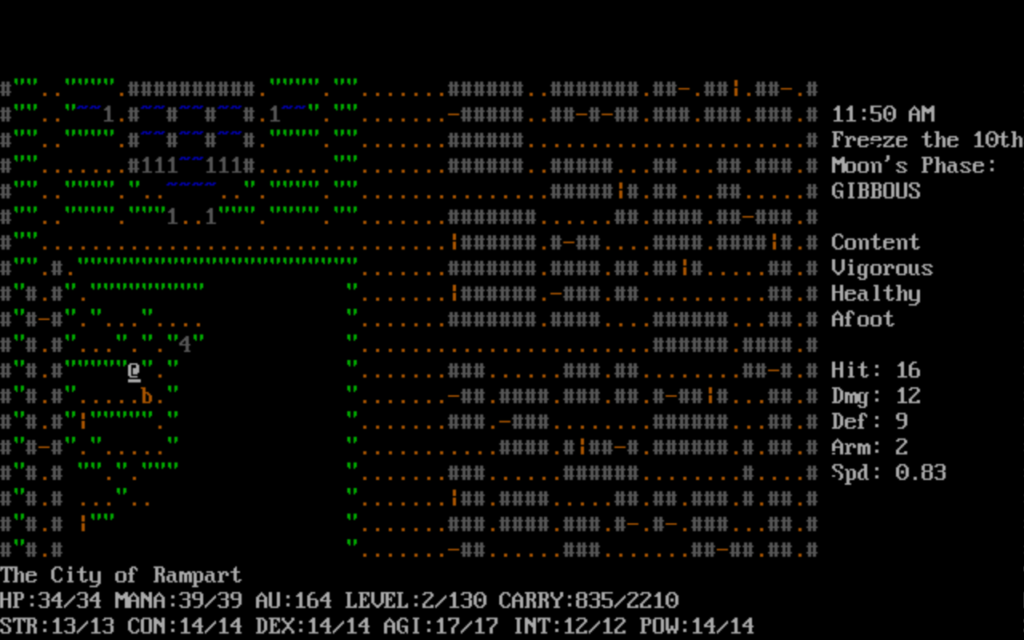

The game world is like that of ADOM, with an overworld, a sprawling sequence of above-ground terrain, with locations in it to find and explore that are in the same places every game. It’s the contents of these locations that are randomly generated every time you play. The dungeons are generated and persist, but only if you don’t enter another dungeon; if you go into the Goblin Caves, then leave and go to the Sewers in the city, when you return to the Caves they will have been refreshed. The layout will be the same, but the map will be forgotten, and the monsters will be different. A player can take advantage of this fact.

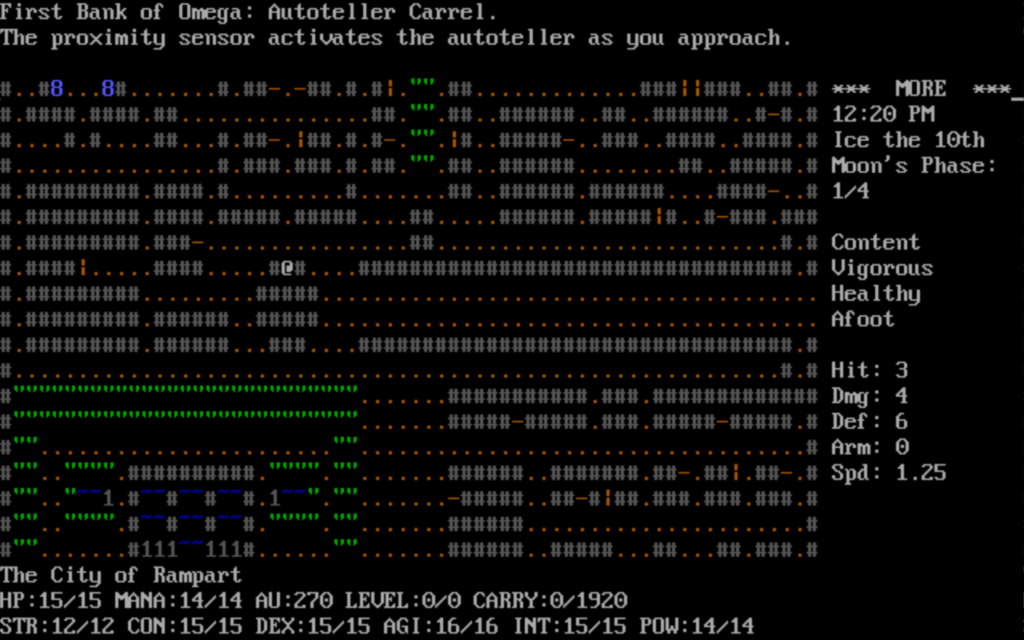

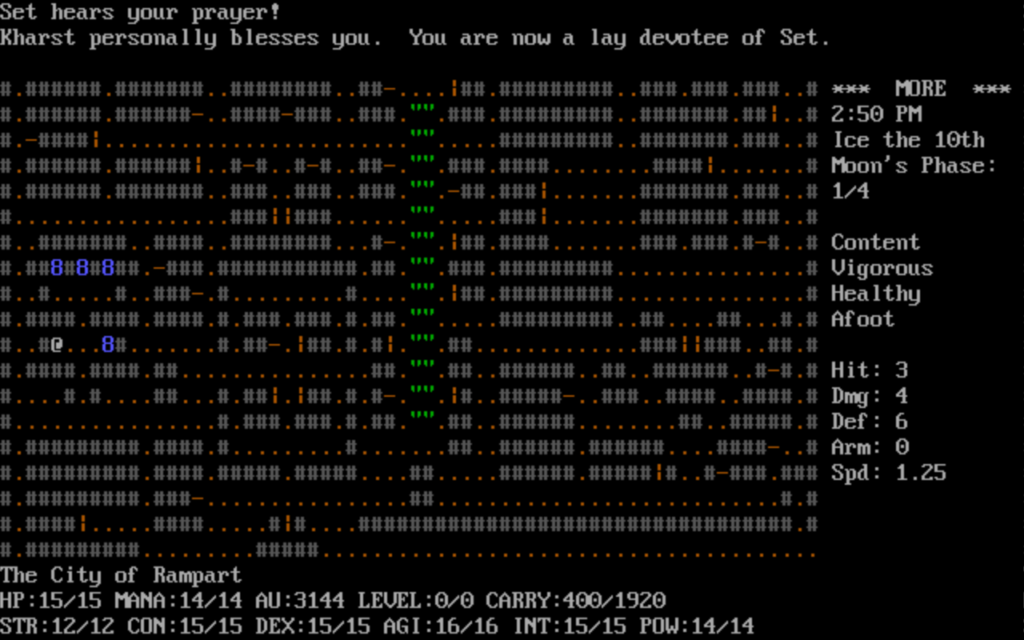

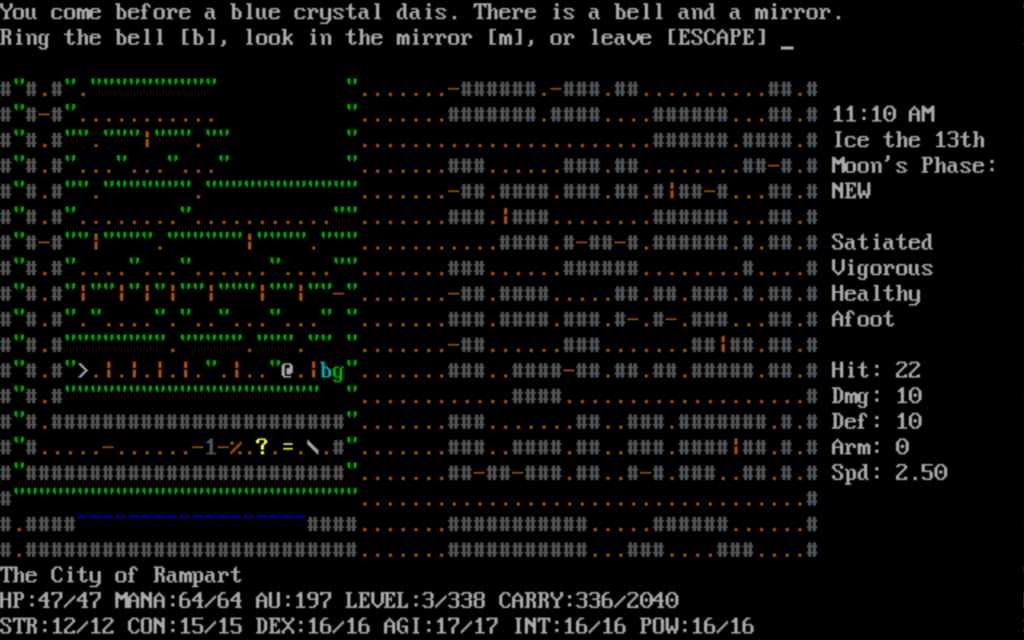

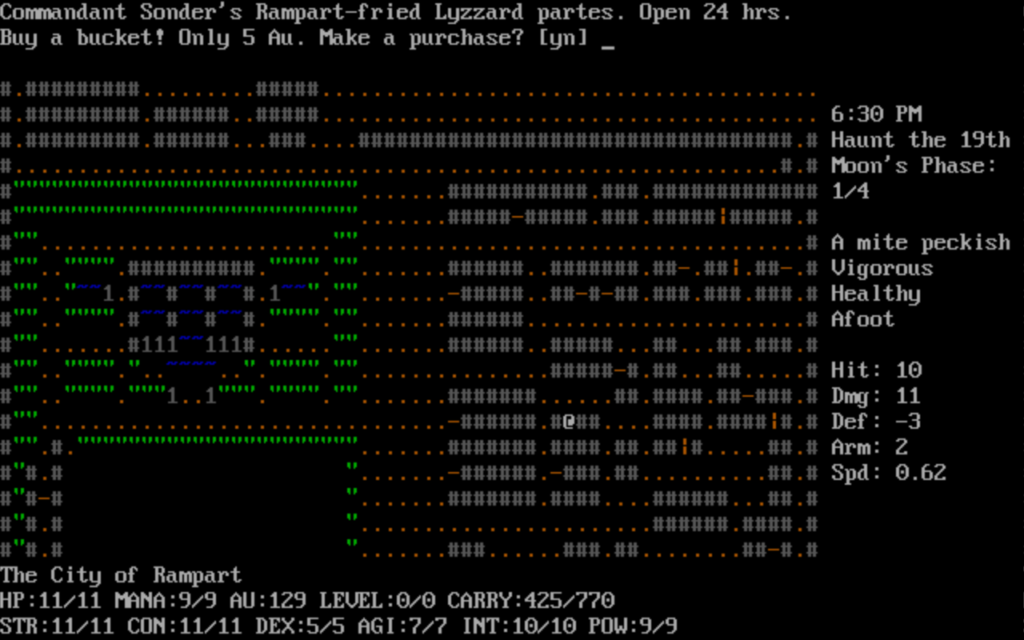

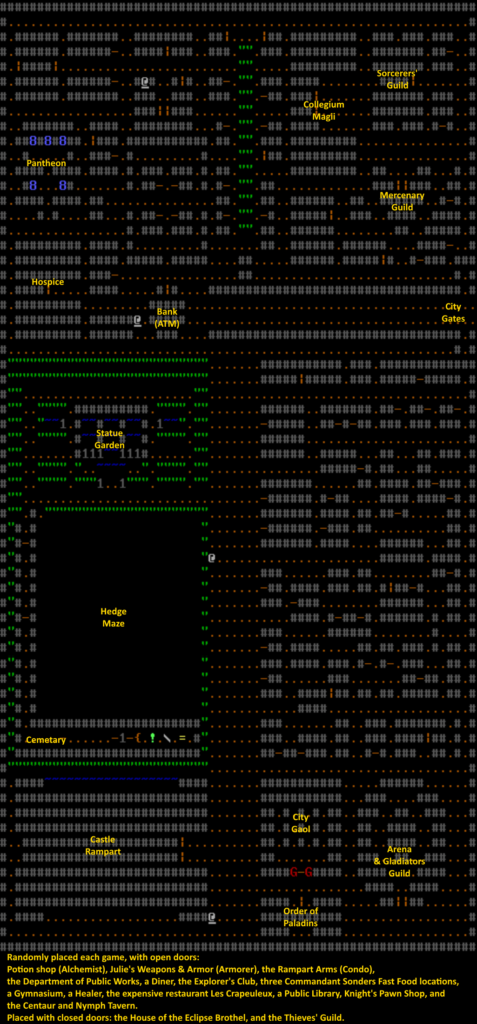

The other kinds of locations seem to remain the same each time, although the city of Rampart, the main urban location in the game and the place where you begin play, has mostly the same map every game, but the contents of the buildings are mixed up when the game begins, and its hedge maze area is selected from one of a number of possible layouts. Rampart is the center of the game in many ways. Most of its guilds are based there, and to advance in them and get many of their benefits you’ll have to return to haunt their doorsteps. There are other settlements in the game, but none of them are anything like Rampart. It’s a cool location. It might be the greatest city in all roguelikedom.

The Layout of Rampart

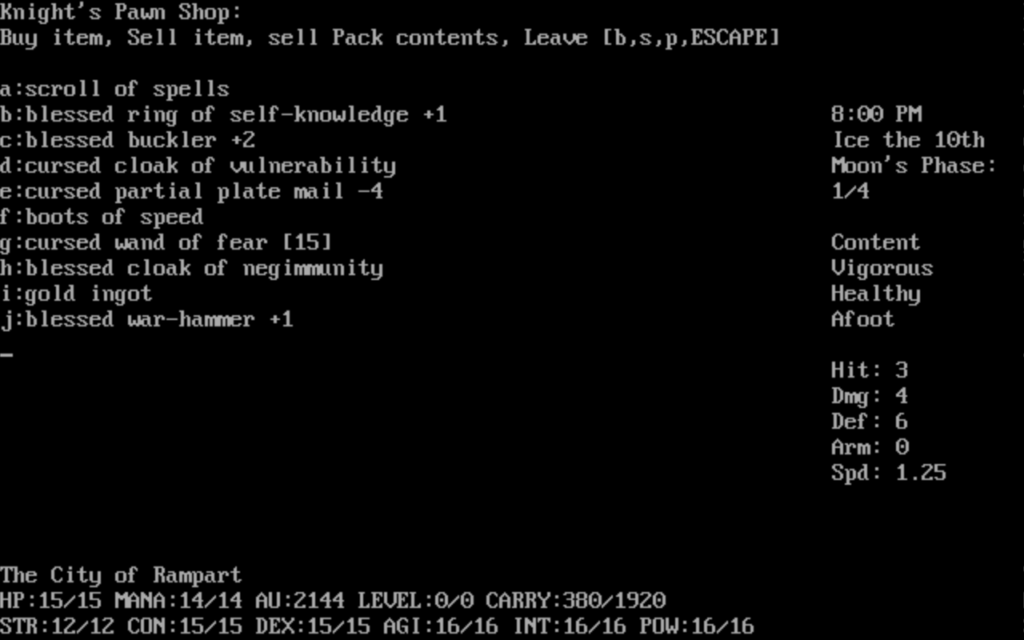

Rampart is the largest city in the game, and where your journeys begin. It’s a good place to pick up supplies, decide which guilds and religions you want to join, and get equipment.

Places in Rampart with set locations, and randomly-placed locations once you’ve discovered them, can be moved to quickly with the Automove command (Shift-M). For more information on the city and places of interest within it, I must ask that you wait until next time. Until then, why not explore on your own, and see what you can figure out? All you have to lose is maybe twenty or thirty lives.

Basic Keys

?: Help. Provides a lot of information about the game and its systems. Refer to the ‘l’ option here for more keys that aren’t listed here.

- numpad/vi keys: walk, bump into enemies to attack them

- numpad 5: run

- .: Wait 10 seconds, note this is twice the length of time it takes to move a step

- ,: Wait a specified number of minutes

- s: Search surrounding spaces for secret doors or traps

- i: Inventory (explained further down)

- x: Examine something in a location in sight. (very useful for distinguishing what monster or item is on a space)

- g: Pick something up at your feet. (Think of it as ‘g’ain)

- e: Eat something

- q: Drink a potion (‘q’uaff)

- r: Read something

- a: Zap wands and rods (think of it as ‘a’pply). Note, to be used, most items must be worn on your person. You can’t just use items out of your pack, you have to get them out first.t: Talk to someone. This is used to greet some characters and threaten monsters. Talk with and greet a horse you own to ride it.

- f: Fire a weapon or throw an item.

- o: Open door. (used frequently)

- c: Close door. (used less often)

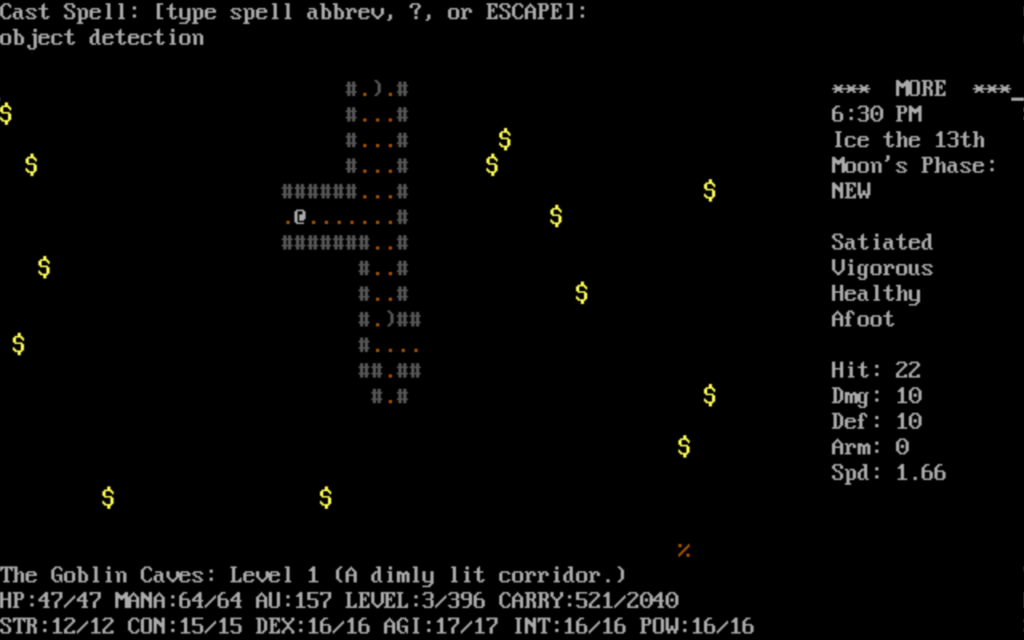

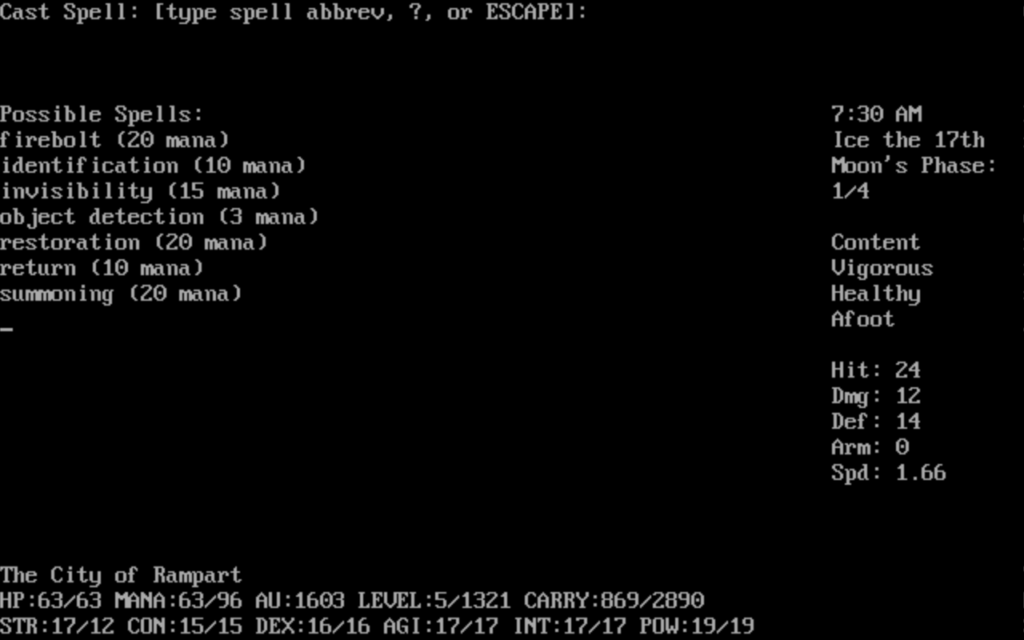

- m: Cast a magic spell. You specify which spell you want to use by entering its name. You only have to enter as many letters as to distinguish the spell from the others you know.

- Shift-A: Use miscellaneous items or artifacts. The item that lets you escape the Arena when you win a fight is of this type.

- Shift-F: Change your attack routine. (‘F’ight)

- Shift-S: Save the game (supply the filename as an argument on the command line to load the game)

- Shift-T: Tunnel through a wall (use in moderation)

- Shift-M: Autotravel to a known location in your current town. Places that are the same from game to game are automatically known, randomly-placed locations must have been entered at least once. As with spells, you enter the place’s name, but only have to enter as many letters to uniquely identify your destination.

- Shift-E: Get off your horse.

- Shift-D: Disarm a trap.

- Shift-G: Give an item to someone.

- Ctrl-I: Look in your pack.

On Inventory

To use most items, they can’t just be in your pack, but must be in one of your equipment slots. Your “Ready Hand” slot and your three Belt slots can hold almost anything, and are good ones to use for single-use and miscellaneous items. I like to keep food in the ‘e’ slot of my belt.

- x: E’x’change the up-in-air item with the one (if present) in one of your inventory slots.

- s: Show contents of your pack.

- p: Stash the up-in-air item in your pack.

- t: Take an item from your pack.

- d: Drop an item from the selected slot

—–

I’ve got much more to say about Omega, but this article is already much longer than I wanted it to be! There’s so much ground to cover that I’m increasing the post frequency of @Play for a bit, so you won’t have too long to wait for the next part. In the meantime, you might find these links to be of interest….

- First, there is the venerable Omega Distribution Page. It’s a treasure, a genuine relic of the Old Web. The first version of it saved to the Internet Archive is from February 1999. Throughout the years it’s been updated sporadically, but it’s still around. Note, the DOS version of 0.75 listed there is mislabeled. It’s actually for OS/2!

- Donnie Russell II has a number of roguelike games ported to Javascript, and one of them is Omega.

- A number of people have made forks of Omega through the years. GitHub has a few of them: ported to C++, ported to Windows with tiles (here’s its homepage), and two attempts at an “Omega-NG.”

- For those still using Amigas, a port of Omega was distributed way back on Fish Disk 320.

- For other writing on Omega, there’s the CRPG Addict’s notes on the game from back in 2011, in seven parts: first – second – third – fourth – fifth – victory – final rating.

- And finally, way back in 2003 was Boudewijn Waijer’s Omega home page (Wayback link), part of his roguelike homepage collection.