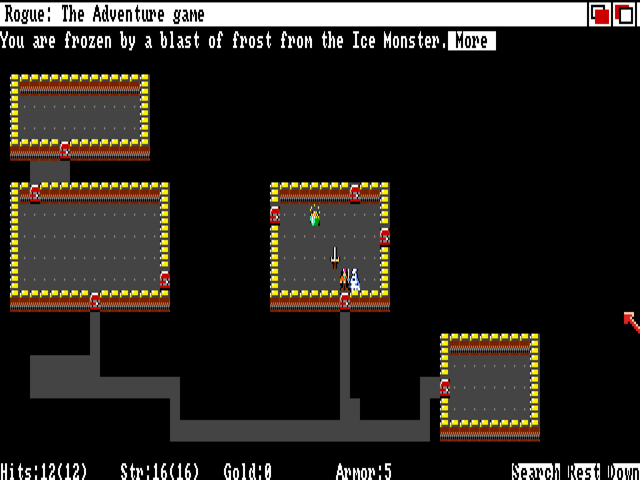

Chunsoft has announced a new Shiren the Wanderer game, Shiren the Wanderer: The Mystery Dungeon of Serpentcoil Island, for Nintendo Switch, due out on February the 27th! Some of the most popular columns from @Play on GameSetWatch were the screenshotted play I demonstrated of the fan translation of Super Famicom Shiren, and if the comments on the trailer are something to be trusted, there’s still a diehard group of fans out there.

Interestingly, the theme of this one is “back to basics,” suggesting that some of the greater mutations of the more recent games, like the Night rules, equipment experience and such, will be pared back. Some of those rules I like and some I don’t, but I have said that more recent Shiren games, while fun, feel like they’re lacking something. Some of the series enhancements starting from around Shiren 4 (which never got an official English release) I have issues with, particularly, monsters always going straight through blind intersections if they have no knowledge of Shiren’s location, allowing the player to take advantage of the AI to avoid conflict; and that Shiren’s healing rate actually decreases, not just relative to maximum HP but in absolute terms, as he gains experience levels. These are relatively minor qualms though, and most players won’t even notice them.

Here is that trailer:

Some noteworthy elements are the return of Shiren’s lady friend Asuka (who despite appearances is several years older than him), and of giant-sized boss battles, possibly using some of the engine enhancements done to facilitate large Pokemon in Rescue Team DX. I also appreciate that the story appears to be a naked grab for loot! It’s always felt to me that a wanderer’s life is, or should be, a hard-scrabble existence, and while our rogueish characters may affect the fate of the world, they’re still usually in it for themselves. That way, if they fail (and they fail often), you can laugh at them more than feel sorry for them.

I keep trying to do more @Play columns but other work continues to get in the way. I have a fair number of subjects to write about now though, not the least of which being my ill-advised decision to buy the super-skeevy Omega Labyrinth Life on Switch. I feel like paying money for that might have gotten my name on a list somewhere, so I might as well get some column inches out of it!