Well, there’s been another Nintendo Direct, yesterday it was. And while there wasn’t much news on the Switch 2, one of the announcements was that there will be another Nintendo Direct on April 2, in just five days, about it.

The presenter this time was (check Wikipedia) Senior Managing Executive and Corporate Director Shinya Takahashi. He has some charisma, but we’re still a long way from the days where Shigeru Miyamoto, Reggis Fils-Amie and Satoru Iwata would co-host, one time as puppets.

Sometimes I take one of these videos and I riff on the games revealed, and the specifics of their revelation. To remind: the narrator’s delivery style gives me a rash, so I’ll try not to bring that up for literally every trailer. Operation 2025 Snark Go (37 minutes)!

Cold Open: Dragon Quest I & II HD-2D Remake

After DQIII, these couldn’t be far behind, but it looks like substantial new content has been added, including a new character? The mainline series has been dropping references to the old Erdrick (a.k.a. Loto) games, maybe this connects to that?

Nintendo Direct for Switch 2 coming April 2

We already explained about this. I don’t know why they didn’t just pile it all into a single video, but it isn’t like people are going to miss out on the news.

No Sleep For Kaname Date – From AI: THE SOMNIUM FILES, from Spike Chunsoft

It’s a visual novel style mystery adventure from the people who brought us the Mystery Dungeon series. Of course, they’ve made lots of visual novels, but in my view that distracts from them making more Mystery Dungeon games. I’m a bit upset by the news that Shiren 6 sold like one-tenth what it has in Japan. What gives, y’all? Show them some love!

RAIDOU Remastered: The Mystery of the Soulless Army, from Atlus, out June 19

Atlus’s turn to make a Very Japanese Game. This one is a remake of a Playstation 2 entry in the Megami Tensei series. It stars a mystery-solving apprentice detective who can also summon devils to help him in turn-based battles. If he can summon devils, one is given to wonder, what does he need the trainee detective gig for? I guess consorting with the Underworld doesn’t put food on the table.

Shadow Labyrinth, from Bandai Namco

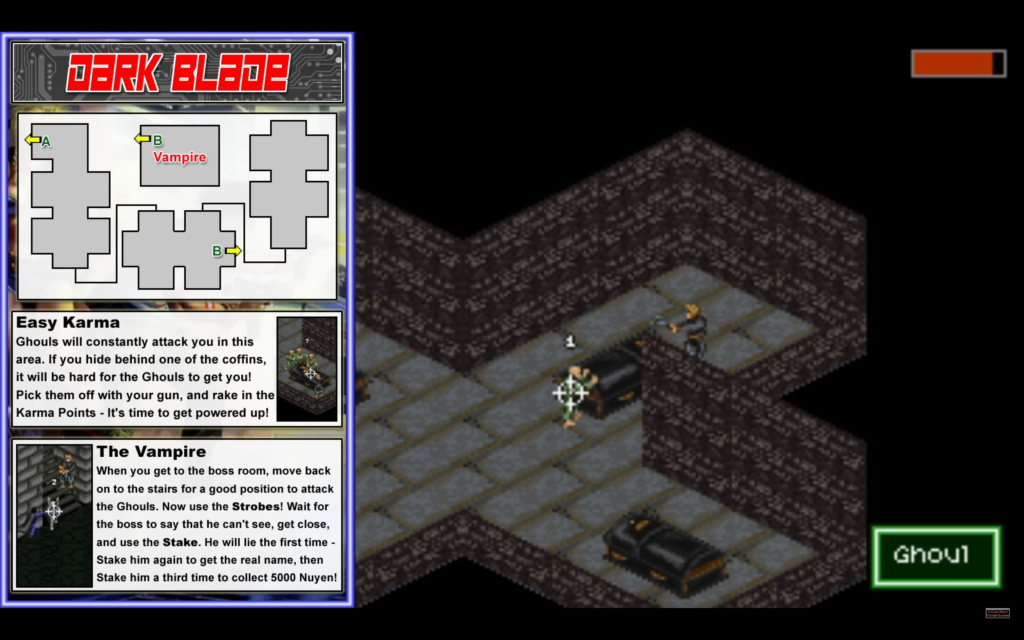

Those two games are fine, not my usual thing but I recognize their merits. But this one, I don’t know….

I feel like, for the most part, Bandai Namco doesn’t really know what to do with Pac-Man. Well, I can tell them what to do: make more Pac-Man Championship Edition! It’s that easy, oh and also police their high score tables much better for hacked plays, Pac-Man CE 2’s scoreboards are overloaded with impossible scores. Or else, maybe more Pac-Man World games? Getting their ducks in a row with GCC and getting back the rights to Ms. Pac-Man? Instead we have one of the least necessary games we’ve seen in many a generation: the dark and gritty reboot to Pac-Man.

“With your memories gone, you have been summoned to a strange, unfamiliar world… where you’re greeted by a yellow orb known as PUCK.” Oh brudder, ignoring that we’re talking about Pac-Fucking-Man, that’s three hoary game trailer clichés in one sentence!

“But who is this spherical stranger?” ITS PAC-MAN. ITS OBVIOUSLY PAC-MAN. EVEN IF IT ISN’T PAC-MAN FOR LORE REASONS, IT’S PAC-MAN.

“Moored in a mysterious, maze-like world…” AUGH “…your battle for survival begins.” The narrator is giving me a rash again.

“Experience a dark twist on the iconic Pac-Man…” JUST GIVE US PAC-MAN CE 3. THAT’S ALL YOU HAVE TO DO NAMCO. Sincerely, someone who’s gotten in dozens of hours of every previous Pac-Man CE game.

Patapon 1+2 Replay, from Bandai Namco

Ah, this actually looks interesting! But wasn’t Patapon a Sony thing?

You guide a tribe of primitive shapes with big eyes through a rhythm-based battle game. You give orders to your troops by tapping different buttons in the right rhythm, and their attack power comes from your timing. The original Patas-pon were PSP games, and the Switch is kind of like a PSP in its way. I’m still surprised this isn’t on a Sony platform though.

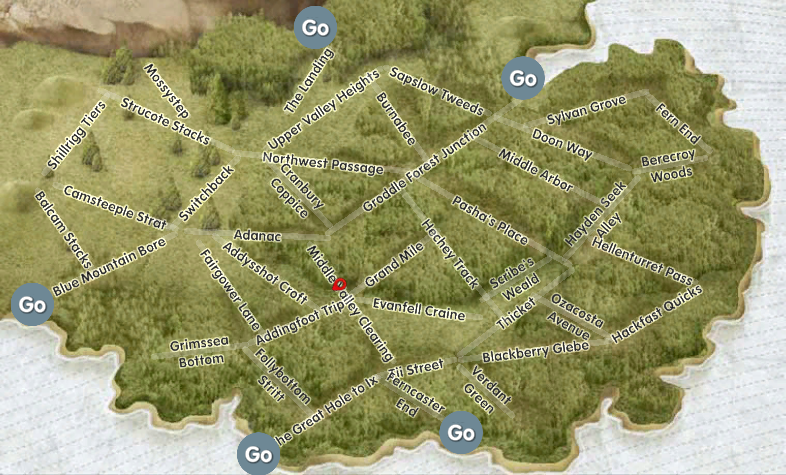

Story of Seasons: Grand Bazaar, from Marvelous

Another Harvest Moon, this one for the Nintendo DS, given a trademark-unencumbered remake on the Switch. Predictably, you play as a young farmer trying to make a place for themself in a new town, growing their suspiciously large vegetables and milking their hippo-like cows. Eventually they can hook up with one of several eligible spouses, giving it the veneer of a dating sim.

It’s a formula that Stardew Valley more-or-less perfected, and Harvest Moon went to the well so many times that I wonder if the features are just permuted in different ways now, but the series has a lot of fans and they’re pretty amiable.

Metroid Prime 4: Beyond, from Retro Studios and Nintendo, some time in 2025

A lot of people are looking forward to this one, and we finally have some substantive information on it. In this one Samus gains yet another new suit, what is it five by now (how does she pee in those things?), and psychic abilities. Samus is already a super-powerful cyborg wearing a power suit with a half-dozen kinds of deadly beams, can inexplicably roll up into a ball, and can basically fly in some games. Now she can move things WITH HER MIND too? When she inevitably loses her power suit at some point during this game, will she get to keep her mind powers?

The problem with the Metroid series is, the most intersting thing about them is Samus, but the title is “Metroid,” so Metroids have to be in every game. Samus could carry a game that doesn’t have anything to do with Metroids! I mean, the main antagonists are called, just, “space pirates.” They don’t even have a name as a race! There’s been hints that the main series will stop featuring them, although what it’ll be called in the future isn’t clear. Anyway, there’s a creature like a Metroid in this one, so I guess they’ll have at least one last hurrah.

Disney Villains Cursed Café, from Disney Games, out now

My eyes are nearly rolling out of my head. It’s another attempt by Disney to take some trend and wring lucre out of it using their IP. This time it’s a small business sim, where you serve Disney villains “potions.” You’re a “potionista.” Since it’s an excuse to throw together characters from vastly different properties it has some crossover comedy potential. Ursula and Maleficent hang out around with the likes of Captain Hook and Cruella DeVille. You get many different kinds of evil all thrown together as if they were the same thing.

You buy your ingredients from Yzma, from The Emperor’s New Groove, which I think is kind of unfair. While later elaborations upon its milieu make her more of a villain, in the original movie she’s more of an anti-hero? Kuzco, as an uncaring emperor trying to tear down Pasha’s village, was the real villain, and Yzma’s plotting against him was arguably in service of the Inca kingdom.

Gaston is your assistant in the game, which raises the question… how evil are you? Are you planning on taking over the Disney world? Or maybe, Disneyworld?

Witchbrook, from Chucklefish, available Holiday 2025

Chucklefish, a publisher that consciously adopts pixel art as a theme, has a number of successful games, including Starbound and Wargroove, but their best-known game is one they no longer publish: Stardew Valley. Witchbrook looks like it has similarities, although it applies its grid-based aesthetic to a pseudo-Harry Potter setting. But it’s got the romancin’, and the four-player co-op’n. And given how J.K. Rowling has succumbed to Internet Poisoning lately, a game in that kind of universe that isn’t so tainted with anti-trans rhetoric will probably be welcome, if the very idea hasn’t been ruined by its association with her.

The Eternal Life of Goldman, THQ Nordic

The always-breathless narrator explains: “Action, adventure and arcade games await!” Arcades figure not at all in this title though, which is mostly a platformer with a hand-drawn look. “Set off on a fantastical mission to eliminate a mysterious deity in this hand-drawn platforming adventure you’re explore an expansive archipelago where nightmares and wonder collide!” You’re describing a video game, that’s like half of them! Other than the admittedly charming artwork, we just don’t know much about this one.

Gradius Origins, from Konami, August 7

ARGH the narrator pronounces it “gray-dius!” It’s “grah-dius,” I continue to insist! GRAH-DIUS!! I can accept a short A, but never a long one! The included games are the arcade versions of Gradius, Salamander, Life Force, Gradius II, Gradius III (oh frog) and Salamander 2. Shown off is the fact that Gradius III has multiple versions, which is welcome news since the original arcade release is infamous for its length and difficulty. The whole series also has terrific music; hopefully there will be a jukebox mode for players who can’t take G3’s infuriating gameplay.

The collection also includes a new game, Salamander 3! Okay, I have to get this now.

Rift of the NecroDancer, from Brace Yourself Games, out now

A more traditional kind of rhythm game than its roguelike predecessor. They appear to be approaching other indie games with great music for paid DLC packs. A Celeste music pack DLC is available immediately, and notably, Peppino from Pizza Tower was shown off in the trailer as an upcoming expansion. Pizza Tower had some of the best music in all of video gaming, so it’s worth looking forward to.

Tamagotchi Plaza, from Bandai Namco, June 27

Tamagotchi’s logo still has the egg virtual pet device in it. Do they even still make those things? I haven’t seen one in a store in the States in decades. Tamagotchi games are sometimes better than you’d expect, especially from a property that’s now two decades past its best-by date. As always, it looks like a meltdown of the Sanrio characters, and has that kind of feel to it.

Pokemon Legends Z-A, from Nintendo/Creatures/GAME FREAK, late 2025

I guess the various companies involved decided they weren’t getting enough billions of dollars lately. “You’ll begin your adventure by choosing one of three partner Pokémon!” Literally everyone who’s watching this already knows that! (By the way, all the many accent-Es in this piece are brought to you courtesy of the Compose Key.)

“To make it easier for humans and Pokémon to co-exist, a company called Quazartico Inc. is carrying out an urban redevelopment plan!” I wonder who the villains will be, hmm.

“If you’re spotted, they’ll challenge you to battle!” Has anyone in any Pokémon been able to resist accepting a Pokémon fight, even if their last ‘mon is down to Struggling? JUST SAY NO TO TURN-BASED SANITIZED COCKFIGHTING. And it’s still nearly the same battle system as shown way back in Pokémon Red and Blue! Haven’t they exhausted its strategic possibilities three times over by now?

Mega-Evolutions are returning. I guess it shows dedication to something to bring back a previously-used gimmick rather than coining another one.

One of the trainers challenging the protagonist in this one is Zach. Zach opens up saying: “Well, I won’t make it easy for you, because this taxi driver has a taxi dream! I’m going to reach Rank A and abolish all forms of transit in Lumiose—except taxis!” That’s like picking your mayor by whoever has the meanest dog!

Rhythm Heaven Groove, from Nintendo, 2026

This is one I can get excited over. Finally, Rhythm Heaven comes to Switch, and it seems to have a lot of new minigames. Don’t sleep on this one, its many minigames are hilarious.

News: Virtual Game Cards, coming late April

A way to play Switch games on more than one system. Basically, you can de-authorize a card on one system to play it on another system you own. An internet connection is required, but only when authorizing (“loading”) or deauthorizing (“ejecting”).

BUT. It only works on up to two systems without a family Switch Online account, which potentially expands the count by 8 more systems. Local wireless seems to be required, so far-flung families may have problems. And only one game can be lent to a given person at a time, and only for up to two weeks at a time. Seems like a whole lot of catches and exceptions. The system is confirmed to support the Switch 2

Quick previews:

- High on Life, from Squanch Games, May 6

- Star Overdrive, from Dear Villagers, April 10

- The Wandering Village, from Stray Fawn Studio, July 17

- King of Meat, from Glowmade, sometime in 2025

- Lou’s Lagoon, from Megabit Publishing

- Fantasy Life i: The Girl Who Steals Time, from Level5, May 21

- Saga Frontier 2 Remastered, from Square-Enix, out now

- Monument Valley 1 & 2, ustwo games, April 15

- Monument Valley 3 coming Summer

- Everybody’s Golf: Hot Shots, Bandai

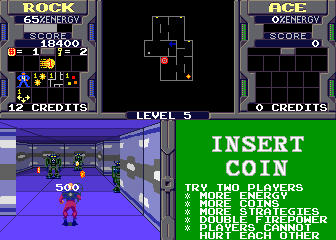

- Marvel Cosmic Invasion, from Dotemu and Tribute, Holiday 2025

And:

Tomodachi Life: Living the Dream, Nintendo, 2026

Oooh, the prestigous last announcement this time goes to a series that hasn’t had a great amount of luck lately? It’s felt like Miis have been on the outs for a while. Tomodachi Life was last seen back on the 3DS, Miitomo on mobile lasted mere months, and Miitopia, while cool, didn’t build a lot of buzz. I’m glad Nintendo is giving both Miis and Tomodachi Life another chance, though it’s disappointing that it’s being announced so far in advance.

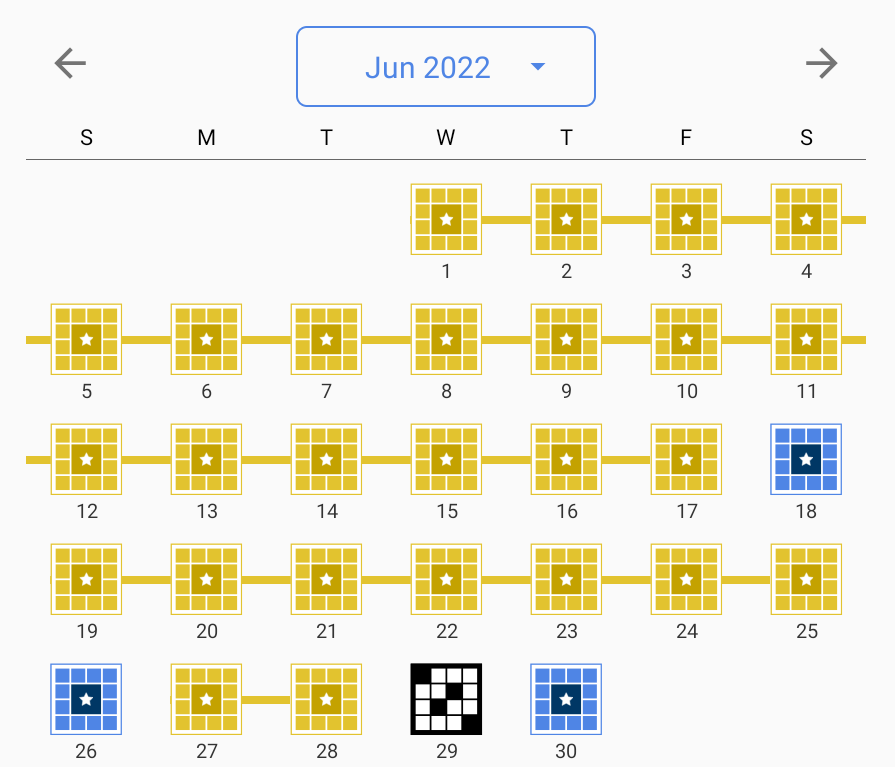

Nintendo Today app

Introduced by Shigeru Miyamoto himself, this is a smart device app that functions as a calendar, and presents daily Nintendo news and content. Huh, that sounds a bit familiar… ahem! It’s available for download now, and news on the Switch 2 will be presented through it as well as in the next Nintendo Direct, in five days.