This is a pretty nifty website that covers a variety of retro-coding topics. Here I link to three recent posts.

#1: CP/M working in a browser

I’ve mentioned before my fondness for CP/M, the first widely-used microcomputer OS, the DOS-before-DOS. My attempts to try to emulate machines using it, however, have mostly gotten snagged on one thing or another. Well they have a post about getting in-browser CP/M working, with information on some of its commands. Here you can run it yourself,

People familiar with MS-DOS should be right at home, although some commands are different. (That’s because MS-DOS changed them; it was originally made as a CP/M clone.) One major difference is the absence, in this version, of disk directories. Instead there were up to 16 numbered “user areas,” each its own individual region on the disk, kept separate from the others. CP/M was an amazingly compact system, a single floppy disk could host a half-dozen compilers and have room to spare.

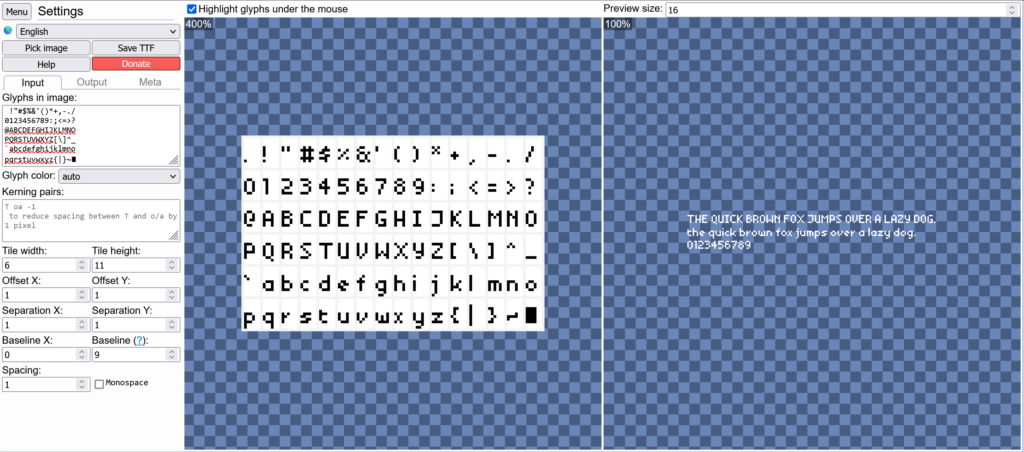

#2: Speeding Up PETSCII

Commodore BASIC was notoriously slow, but also feature-poor. A version of the same Microsoft BASIC that was co-written by Bill Gates himself, and was later ported to MS-DOS as QuickBasic. This page is a collection of different ways to speed up printing PETSCII characters, covering several optimization techniques, one of them, avoiding IF statements, being non-obvious.

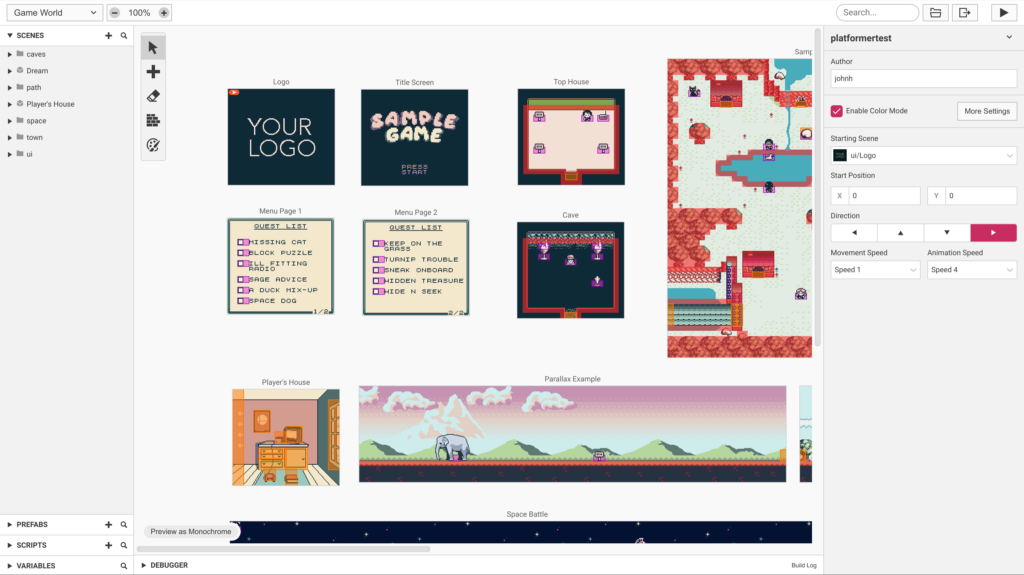

#3 Online Retro IDE

The linked page is actually about a recent update for it that adds support for DOSBox and BBC BASIC. It supports loading your code directly into a Javascript emulator. It supports many other computers and consoles. The IDE itself is here. The update page claims that FreeDOS is available as a platform, and with it another runnable version of Rogue, but I couldn’t figure out how to get into it before posting.