A few weeks back I mentioned Dungeon, a Commodore 64 CRPG system created by David Caruso II and published in 1990 on the disk magazine Loadstar. We’ve made it available through emulation on itch.io for $5. It’s here, and it’s awesome. It’s not just a way to play CRPG adventures but to make them yourself, and it even contains a random dungeon creation feature.

I make it available with some trepidation. Dungeon has a few significant bugs. For example, it supports two disk drives throughout, but if you use its Dungeon Maker then you need to set it for single drive mode, or else you’ll encounter a Disk Error just at the worst possible time: when saving your project. Its randomized “Lost Worlds” often create dungeons that strand your character in impossible situations, and while there is a way out of them, it involves loading the Guild menu 15 times.

But I’ve played a lot of these random dungeons, and I think overall David Caruso II made a clever little game system, and I think his ideas are worth building upon. That’s why I’m working on a remake/update of Dungeon, that I’m calling Dungeon DX.

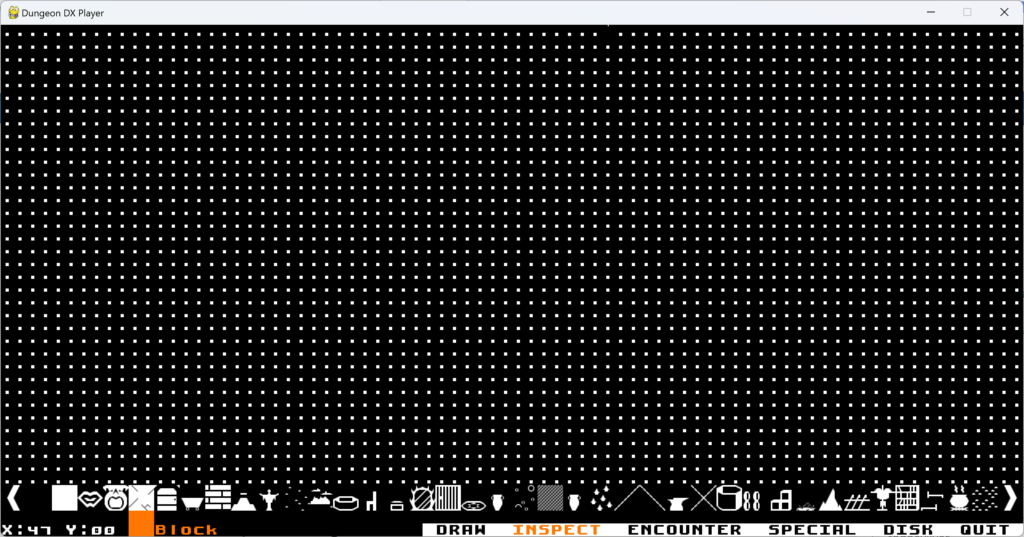

I’m making it in Python using the Pygame library. I’ve tried making a game with Pygame before and had some problems with it (I may bring myself to talk about that experience someday), but using it now I’m pleased to see Pygame 2 has become a lot more performant, and that’s even before trying to compile it into a faster form. I’ve built for Dungeon DX a kind of bespoke terminal emulator, but one with support for loads of cool graphics effects. I’ve made dungeon art and monster images for it using the website Fontstruct, which gives the images a low-tech, but distinctive look.

I’ve been working very hard on it, to the extent that I can feel myself getting my hopes up that a substantial number of people may actually play and enjoy it. Most of the times in the past that I’ve done that I’ve had those hopes get crushed, but hey, maybe the nth+1 time’s the charm?

Besides not having all of its bugs, why do I think this project is worth working on? These are the things I find appealing about the original Dungeon, the reasons that I played so much of it myself, things that I don’t generally see in CRPGs these days:

- It’s not a game but a game system. It isn’t a single huge campaign that you play and finish, and it isn’t a single story. Your characters can keep going so long as there are adventures to be had.

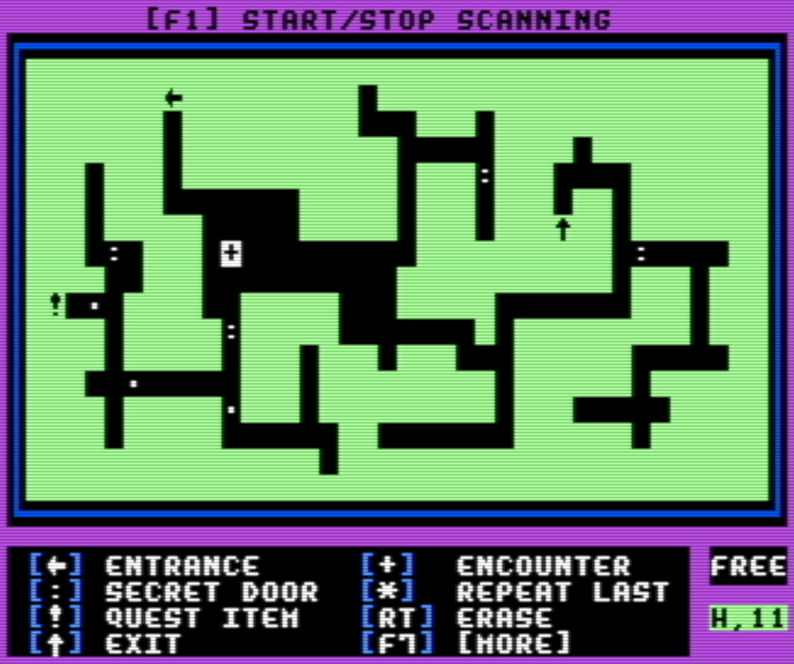

- In structure it isn’t like a novel, but it’s more like a series of short stories. Each dungeon is a single screen, that fills out as your character explores it. That may sound a bit like a classic roguelike, and there are some elements of that, but the feel is subtly different. Each single-screen dungeon usually has more adventure packed into it than in a single roguelike dungeon level.

- It’s like a collection of short stories, but that stars your character as they progress through it. The focus is more on the development of that character as they continue their adventuring career. Like how the Conan the Barbarian novellas are each an episode in the life of a single adventurer.

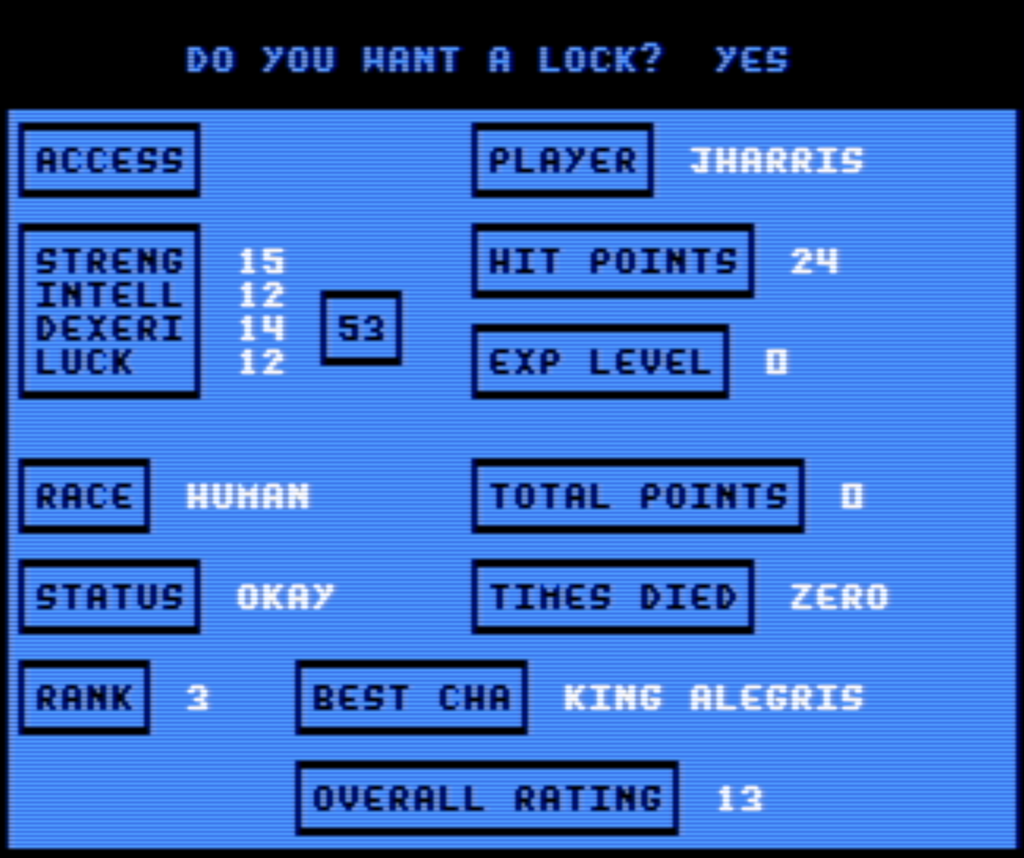

- It features what’s known in some circles as slow character growth. D&D has rapid growth, and it’s gotten even faster as the system has changed through the years. 5th Edition characters advance to second level absurdly quickly, after earning only 300 XP, and that advancement practically doubles their power! 0th-level Dungeon characters (it starts counting at 0) have a lot more durability, but it takes them more time to advance to Level 1, and when they gain it their power only increases a little. In this, a lot more of a Dungeon character’s life is decided at character creation. But it also means, as they increase in power, you know it’s due to your own efforts.

- It’s more simulationist that CRPGs have become as of late. A lot of CRPGs have crept towards gamishness, which generally is okay, I mean they are games after all. But I think RPGs work the best when you can imagine them as being the adventures of real people, so as their power has crept up, and their abilities have gotten more abstract and arbitrary, they have come to feel more and more like playing pieces than living people.

- While there’s a random dungeon maker, you can also make your own adventures for it, and give them to other people! That’s potentially a very great thing. It reminds me of EAMON, an 80s CRPG game system that people could create their own adventures for. (There are still websites devoted to EAMON! It’s a rabbit hole worth exploring, but that’s something more suited for its own post.)

- And finally, it’s hard. Characters die frequently. You can revive them up to three times, and if you don’t mind reloading the guild menu 15 times you can turn the game off to preserve their life, but defeat is frequent without very careful play. You often have to play like a scavenger: take what easy-to-find rewards and successes you can, build your power over time, seek out easy adventures, and don’t take unnecessary risks. Dungeon characters are not heroes, not at first anyway, and if they’re ever to become heroes you’ll have to watch their steps.

Because these are the aspects of Dungeon that I like, they’re the elements that I’m focusing on in making Dungeon DX. My plans aren’t to make it quite as hard, but to still emphasize that these people are not demigods, not yet. A character’s career may be the story of the creation of a demigod, like how Conan, through countless trials, eventually became king of a great nation. It’s kind of a lie that people who rise to greatness frequently do so because of their own efforts, but it’s a pleasing lie, and it makes for a fun saga if you don’t take it too seriously.

My other plans for Dungeon DX, which may change, for while progress has been rapid (because Python is awesome), I’m still iterating over lots of things:

- A retro look, kind of akin to how Dungeon looks on a C64, but still with enhancements. It doesn’t use pixel art, instead using vector graphics created in Fontstruct.

- Dungeon was all one-on-one fights. Dungeon DX should have parties of three characters, fighting enemy groups that can be larger than that.

- Dungeon doesn’t let characters keep items between adventures. For the most part, characters only advance through gaining experience. DX should let characters have a persistent inventory.

- Dungeon doesn’t have any money system at all! DX should both have money and a shop where basic necessities and equipment can be obtained.

- Dungeon doesn’t simulate much of the basis of exploration. My ideas for DX let characters rest in the dungeon, for example, but they must consume food to do so.

- Dungeon has very little graphical splendor. Dungeons themselves are just blocks of green, with black tunnels dug through it, and once in a while a graphic character. That has to change.

- Dungeon’s encounter model isn’t scriptable at all, which limits what can be done. It’s a lot more flexible than you might think it would be, given the C64’s memory limitations, but the edges of what’s possible are still easily reached. I want to change that.

- Dungeon’s magic system is very interesting for its own sake, a collection of 16 spells that are more useful outside of battle than in it. Only one of those spells that does direct damage to enemies! Magic is much more of general utility. While my design has more damage-doing magic than that, I want to keep that feeling that magic is not primarily for harming monsters.

- Dungeon doesn’t let characters learn spells themselves: all magic comes from items that contain it, and depletes with use. There’s interesting things about that system, but it kind of means that high-Intelligence characters aren’t very viable if the dungeon constructor doesn’t give them any magic to use early on.