In 1987, programmers Robert Germino and David Todeshini wrote a weird and obscure Commodore 64 game called The Red Obelisk. It barely made a dent in the market, which is kind of a shame. It’s nearly entirely unique, which is a difficult thing to say of any game 36 years after its publication.

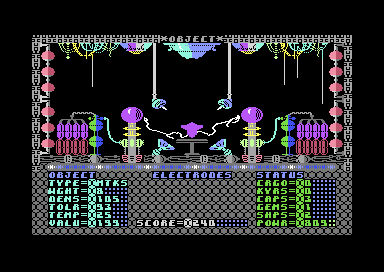

Part of why it’s not remembered much today might be how unique it is. It’s mostly a game about alchemy, but not as much in an Opus Magnum kind of way. You’re given an object, kind of like a gemstone, found in an asteroid belt. You shock it with electricity, zap it with lasers, and shoot sound waves at it. All of this is depicted in an illustrated laboratory, with surprisingly atmospheric graphics and sounds. Doing these things may increase its value. You can sell it at any point to earn energy proportionate to its value, which you need to run your ship and guard against hazards, and points. Your real goal though is to create a Red Obelisk

An earlier work of theirs was Sentinel, of which there’s even less information online.

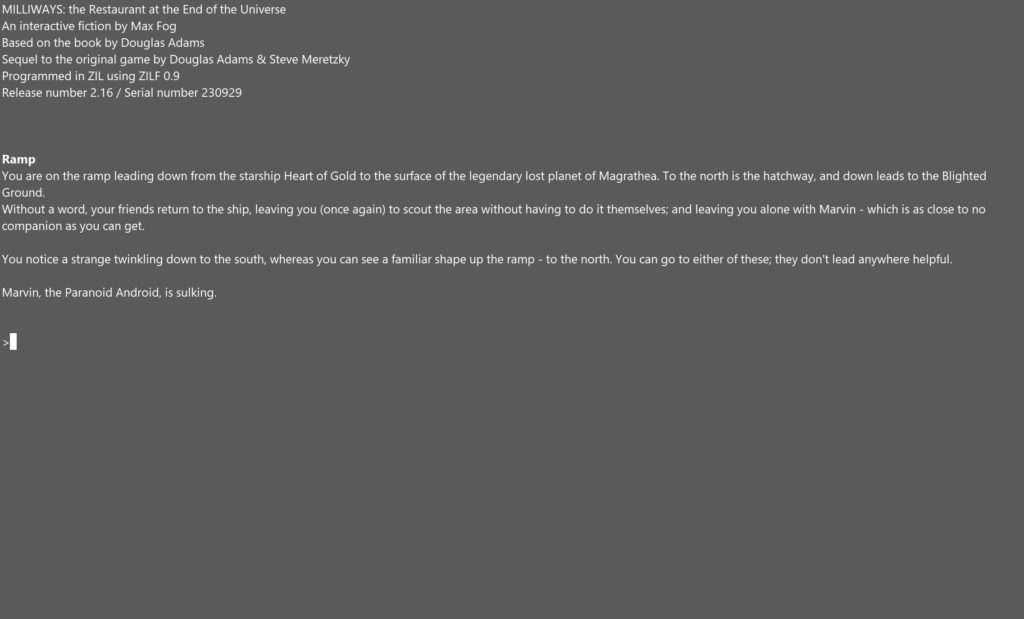

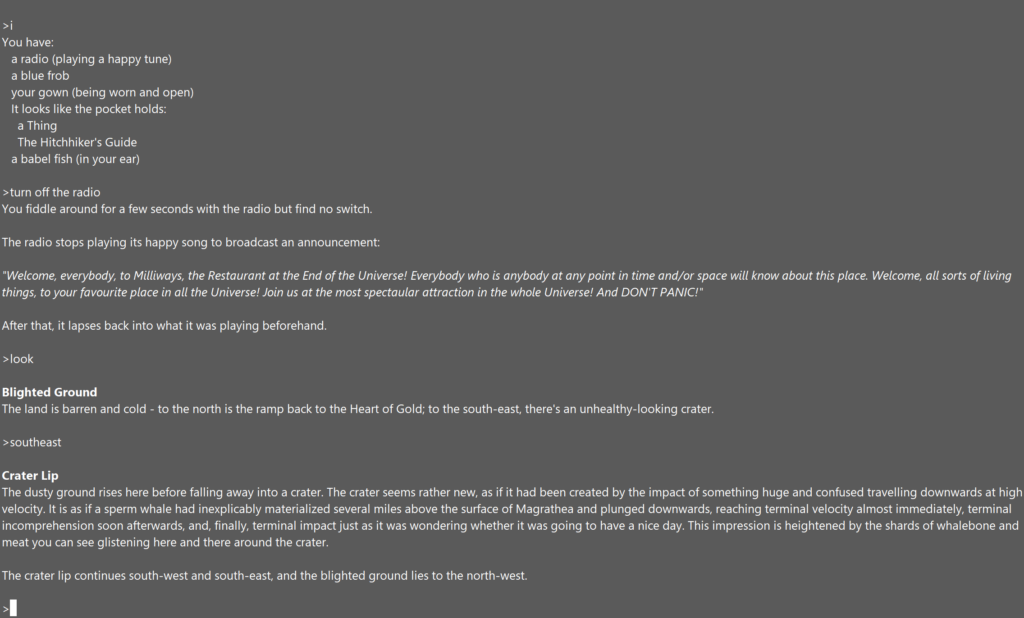

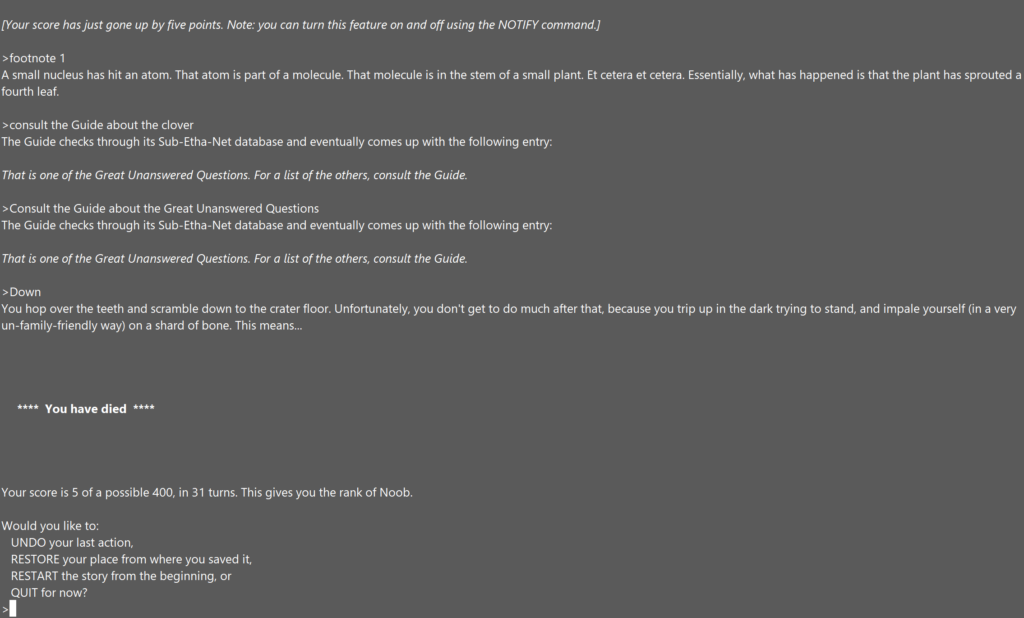

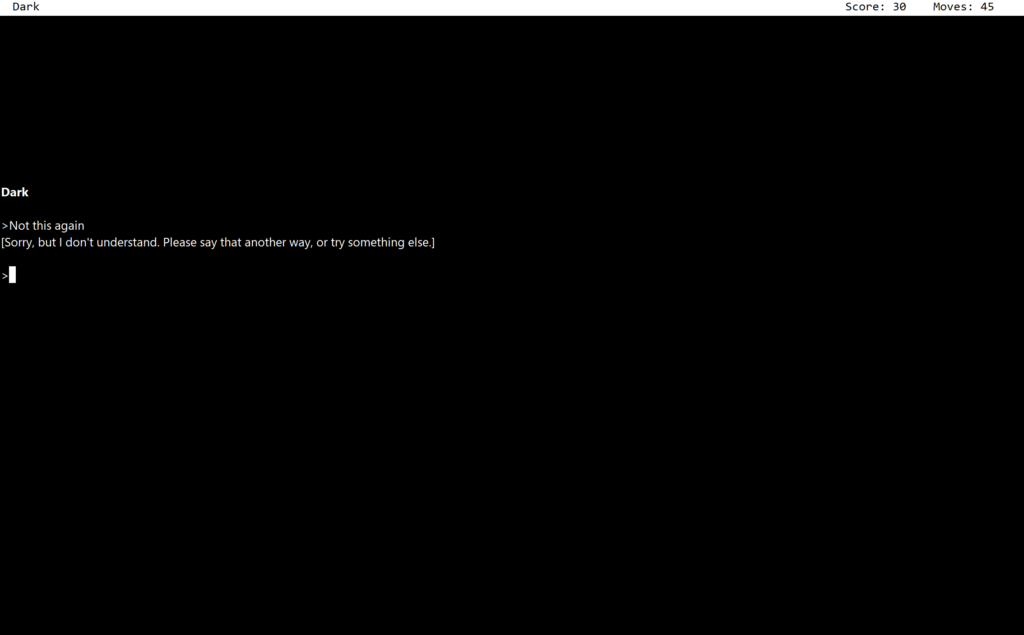

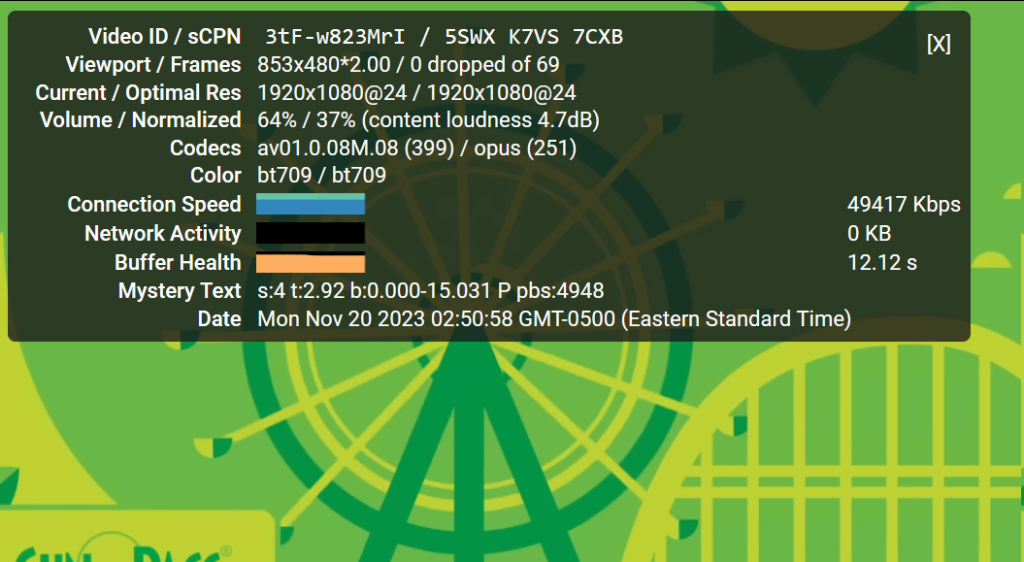

I played a bit of The Red Obelisk and uploaded a recording to Youtube. I don’t do too well. Here is that video (7 minutes):

Both The Sentinel and The Red Obelisk, and another game I think they made called Phaserdome, were included on a disk called Master Blaster put out by Keypunch Software. Keypunch wasn’t a great organization; there are tales of them taking freeware games, scrubbing them of information by which their creators might be identified, and then selling that on a disk. It was before the widespread adoption of the Internet, the World Wide Web was still three years away, so it was easier to get away with that sort thing than it is now.

Later on The Red Obelisk got picked up for an issue of Loadstar, and the veracity of its editors I vouch for completely. I haven’t yet checked their products for the other games. Sentinel is also on Loadstar. The documentation I retyped below suggests they have another game on Loadstar as well. Both The Red Obelisk and Sentinel are on the Internet Archive, but you can get legal and paid-for copies for $15 of the first 199 issues (Loadstar was amazingly long-lived) via LOADSTAR COMPLEAT, still sold by its long-time Managing Editor, my friend Fender Tucker. The Red Obelisk is on LS64 issue 58.

The game is fully described in its instructions, below, so I’ll just give you some of my own impressions. It’s interesting! It has to have something to it for it to have persisted in my memory for so long. I think the game is implemented in BASIC with some machine code routines to handle the real-time portions. This is a perfectly valid way to implement a game; I did it often myself back then. It’s pretty much the only way to get the smoothly-moving asteroids and slick sound effects the game has.

What I remember the most is the Object Mode, where you zap various objects on your workbench in the hopes of creating a hugely valuable Red Obelisk. Everything you do costs energy, and running out destroys your ship, so efficiency is a must. In order to succeed you must take notes as to how each object behaves. Basic directions are given in the instructions: get the Tolerance below 100 with electricity, and the Temperature above 500 with lasers. Is that all there is to these tools? It has been too long for me to remember, but I do remember finding a string of Red Obelisks at one point, so there must be some process to it. Experiment to see what you can find.

The other thing I remember is the noise that your ship makes when you collect an object. All of the sounds in The Red Obelisk are effective, but that noise found a home in my brain when I played it decades ago, and it has never left. I think it probably never will.

What follows are the instructions to the game as included on Loadstar 58, as written by Fender himself, with section headings and minor formatting added by me.

THE RED OBELISK

by Robert Germino and David Todeschini

One of the safest bests of the 21st Century is that treasures will be found in space in the form of small meteors. They may be grey and drab-looking on the outside but inside will be jewels and precious gems, just waiting for the mining engineers to extract them. But it won’t be easy.

If you are a veteran of the universe of STURGRAT (on LOADSTAR #54) you will have an idea of the complexity of 21st Century space mining.

Setting

In THE RED OBELISK you are in control of a mining company. You must gather some object from space and by using the powers of your factory, you can ‘sell’ them for the maximum profit. Your goal, as is any capitalist’s, is to garner as many shekels as you can.

Let me describe your ship first. It is a Sturgrat space mining/laboratory and short-range fighting vessel. It operates in three modes, the Object Mode, the Mining Mode and the Attack Mode. You begin in the Object Mode (which is the inside of your laboratory) where you get a readout of all the capabilities of the Sturgrat.

Object Mode

The most important thing to keep your eyes on is the POWR rating in the lower right of the screen. If this gets too low, you will lose your ship, and, as is shown right above the POWR display, you only have two, not counting the one you begin with.

But your power is running down so you can’t tarry too long making decisions. And believe me, there are a lot of them to make.

You begin with an object on the conversion table. Its type is shown on the left. The idea is to process this object and then convert it into SCORE and POWR. You have to get the tolerance down and the temperature up.

These two values are shown on the left, TOLR and TEMP. You hold down the E key (for the electrodes) for a short period of time and notice that when you let up the TOLR has gone down. Get it down below 100. Press L (for the lasers) the same way to get the TEMP above 500. Since your POWR is going down all of the time, it pays to do these two things quickly and efficiently. They MUST be done for each object.

In the bottom left hand corner is the value of the object (VALU). As a true capitalist, you will want this figure as high as possible before you convert it into cash (SCORE).

You can increase the value of the object by bombarding it with Ultrasonics. Press U and then push the joystick forward and listen to the pitch of the sound. Press the firebutton and the VALU will increase by a certain amount. If you want to increase the VALU faster, push forward on the stick, the pitch will increase and so will the amount the VALU increases when you press the firebutton.

You can get too greedy with VALU. If you’ve increased it too high, the object will be destroyed and will disappear from the screen.

A good Sturgrat miner will write down the TYPE of object and try to discern the maximum VALU an object of that type can attain WITHOUT destroying itself at conversion. Write this figure down, too.

If you convert at too low a VALU, you will only get the VALU, but if you convert it at just below the ‘peak’ VALU of an object, it’ll be transformed into the incredibly valuable RED OBELISK, which, in more ways than one, is the name of the game. It’s up to you to determine each object’s ‘peak’ value.

You cannot do much more in the Ultrasonics mode. Press U to toggle out of it (if you are in it) and then you are ready for conversion. You do this by pressing RETURN. You’ll either (a) convert it for the present VALU, (b) create a RED OBELISK (which pays off handsomely) or (c) find yourself looking at a dreaded FALSE OBELISK. If you see one of these, you have to act quickly and destroy it by firing Caps at it (the F key) or by bombarding it with Ultrasonics. If a FALSE OBELISK is left to itself it will destroy your current ship and its cargo.

Mining Mode

Which brings up the question: Where do objects come from?

You have to space-mine them. Press the SPACE bar to go from the Object Mode to the Mining Mode. You’ll see your Sturgrat drifting through a meteor field. Use the joystick to maneuver around the meteors trying to capture the small, shining object that is floating slowly across the screen. The object must be captured DIRECTLY in the Sturgrat’s scoop. Even a small bit off-line will cause your ship damage.

You have a tractor beam which you can enable with the firebutton. It will draw the gleaming object up the screen where the action is less hectic.

As a matter of fact, the top of the screen is a safe place where you can scoop up hydrogen molecules with your tractor beam and slowly boost your POWR if you are running low.

You can gather up to nine objects at a time or you can gather just one and head back to convert it. To go back to the Object Mode, press RETURN.

Attack Mode

You begin your stint as space-miner with 3 ships and 3 Caps, but as your POWR gets higher (above 1500 megajoules) your Sturgrat becomes more attractive to marauding space-hijackers. When you least expect it you will be attacked.

The message says that you have lost the object on the conversion table and that the marauder wants to know if you surrender or not. If you surrender, you won’t lose your ship but you’ll have to continue with what you have. If you answer N to the surrender prompt you go to the Attack Mode.

This is the arcade portion of your mission. Move the joystick so that the cross-hairs are on the middle of the attacking ship and press the firebutton to fire. Keep an eye on your POWR level. If you are in danger of losing your ship you can weaken or destroy the marauder with a Giga-Gem by pressing the G key.

Giga-Gems can destroy any cargo that the attacker may have, so you should use them only as a last resort. When you have bludgeoned the attacker into submission he’ll ask if he can trade his cargo for his life. If you feel in a benevolent mood (or in a greedy one) you’ll probably do better accepting his offer and letting him limp off into space.

If you choose to destroy the enemy, you may be able to salvage some of his Caps. If you let him live you may get CRGO (objects), Krystals or Giga-Gems. Base your decision on what you need most.

The Krystals (KRYS) cam be converted in the Object Mode by pressing K. A Krystal is mainly a bonus score you get for defeating a marauder and being kind enough to let him slither off alive.

That’s about it. It will take a little practice with the controls of your Sturgrat but soon you will be grabbing objects and converting them like crazy hoping to find a level for each TYPE of object that will give you a RED OBELISK. As your POWR rating goes up you will have to fight off space-raiders more. Try to get the highest score so that you can head back to Earth a rich man.

As for the trip back to Earth, that’s another game, but one I’m sure Bobby and David will be creating soon. Sturgrat rules! Long may it run.

DISK FILES THIS PROGRAM USES: RED BOOT, RED BOOT 2, RED OBELISK, SPR1, T.RED BOOT

**** End of Text ****