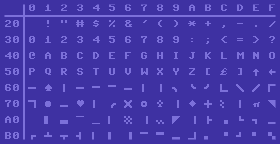

We’ve brought up a couple of examples of Commodore PET software lately, which as I keep saying, is interesting because the PET has no way of doing bitmapped graphics, sprites, or even definable characters. Its characters are locked in ROM and cannot be changed. So, it includes a set of multi-purpose characters that was used throughout all the Commodore 8-bit line, even as late as the C64 and C128, which having definable graphics didn’t need these kinds of generic graphics characters, but they were still useful for people who didn’t want to create their own graphics.

Back on my Commodore coding days I became very familiar with these characters. I think they’re much more universally-applicable for graphic use than the IBM equivalent, the famous Code Page 437, although that’s mostly because PETSCII doesn’t bother defining supporting so many languages. Code Page 437 also uses a lot of its space for single and double-line versions of box-drawing characters, although on the other hand it doesn’t waste characters defining reverse-video versions of every glyph.

PETSCII has:

- A space and reversed space, of course.

- Line drawing characters for boxes of course: vertical and horizontal lines, corners, and three- and four-way intersections. There are also curved versions of the corners.

- More line-drawing characters for borders.

- Still more horizontal and vertical lines, at each pixel position within their box.

- With the reverse-video versions, enough characters to effectively do a 80×50 pixel display, as if it had a super low-res mode.

- Different thicknesses of horizontal and vertical lines too.

- Diagonal lines, and a big ‘X’. Note that on the PET and Vic-20 these lines were all one pixel wide, but on later computers with both better resolution and color graphics they were made thicker, which means diagonal lines have “notches” between character cells.

- Other miscellaneous symbols: playing card symbols, filled and hollow balls, and some checkerboards for shading. On the PET and Vic, the shading characters were finer, while on the other 8-bit computers they were made of 2×2 boxes.

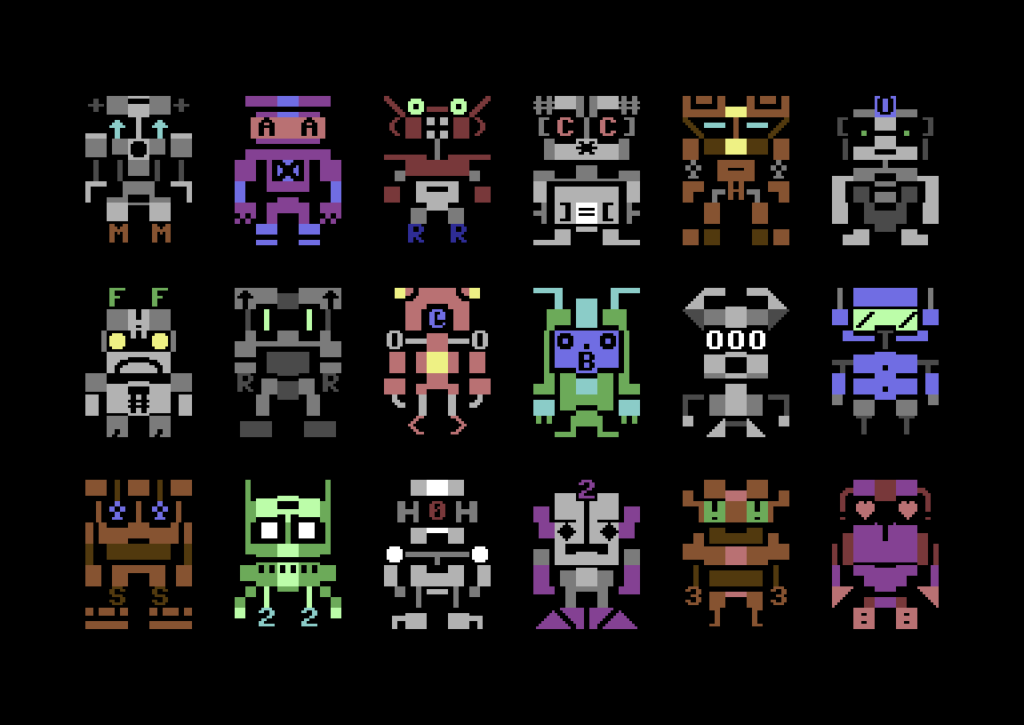

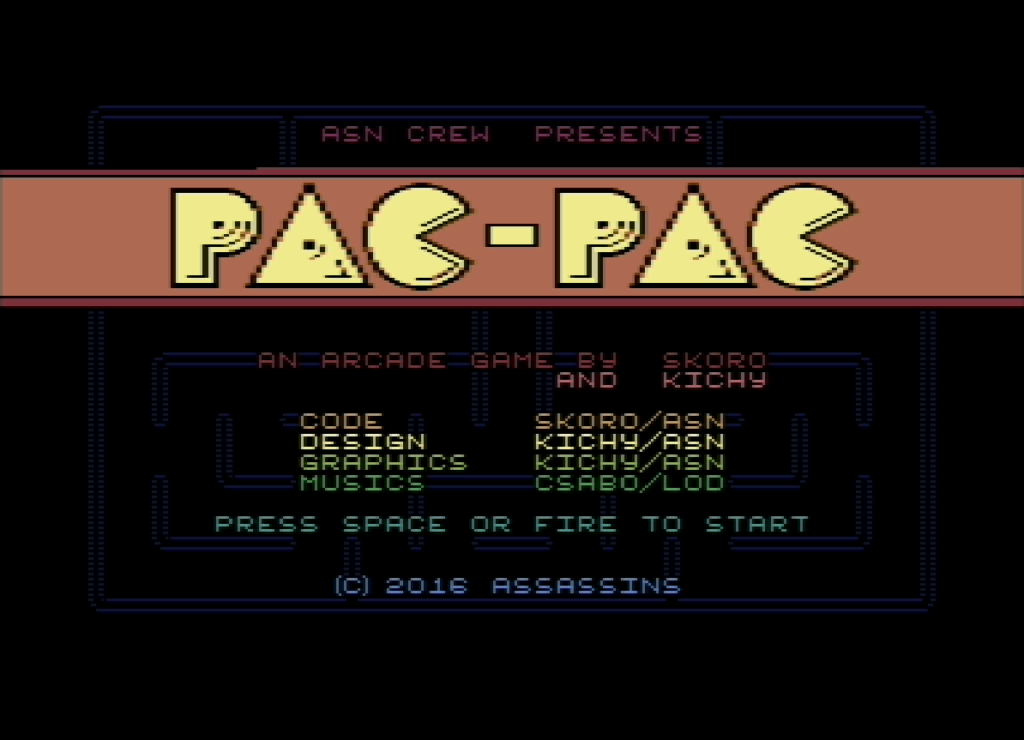

There are resources that let you use PETSCII to create old-school computer art, like this PETSCII editor, Petmate and Playscii, and for a bunch of examples of what you can do with it you can browse through the Twitter account PETSCIIBots. And this blog post from 2016 both makes the case for PETSCII as a medium for art and provides some great examples of it.