“We scour the Earth web for indie, retro, and niche gaming news so you don’t have to, drebnar!” – your faithful reporter

My cell walls are feeling kind of rigid at the moment due to a computer issue that caused me to lose the first draft of this post. All of my witty remarks, lost to the electronic void. You missed out on my entertaining usage of the phrase “odoriferous blorpy.” Truly we are in the worst timeline. It’s all left me feeling kind of cranky, let’s get through it quickly this week.

Ted Litchfield at PC Gamer on a RuneScape player playing a minigame for eight years and turn turning in all his progress at once. RuneScape is an early MMORPG that began in 2001.

Several things to do with Konami, a once-great publisher that’s become pretty hidebound lately:

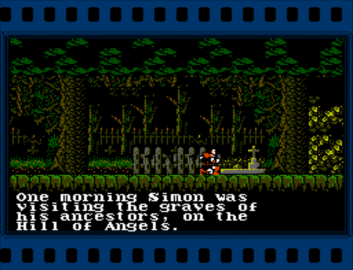

Dustin Bailey at GamesRadar: fans are working on a PC remake of Castlevania II: Simon’s Quest. I’m sure this won’t get obliterated by legal threats. They should have gone with the cheeky route taken by The Transylvania Adventure of Simon Quest. The article mentions that its creators consider the fact that many townsfolk lie to you to be a problem, instead of awesome as it really is.

Charles Harte at Gamespot organ Game Informer says Dead Cells’ upcoming Castlevania-themed DLC is really big.

Also from Charles Harte, Konami is shutting down their recently-released game CRIMESIGHT, not just removing it from the Steam store but even making it unplayable. Great way to reward people giving you money, K. It’s not even a year old yet!:

Tyler Wilde, also from PC Gamer, on a $2,000 game on Steam and what it’s about. Summarized: it costs $2,000 but is short enough that people can finish it within the return period, and it amounts to a screed against women. Blech!

Dean Howell at Neowin: a fan-made decompilation of The Legend of Zelda: A Link to the Past can now be compiled for Windows and (presumably if your device is jailbroken) Switch.

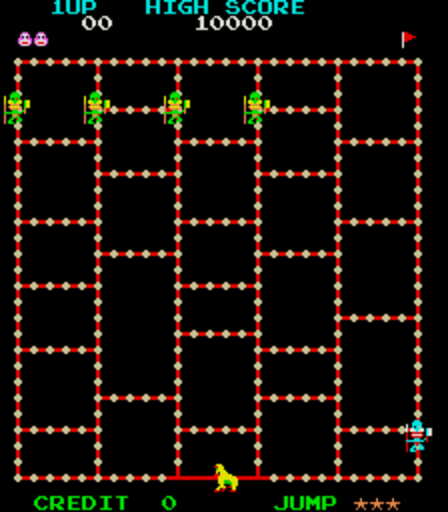

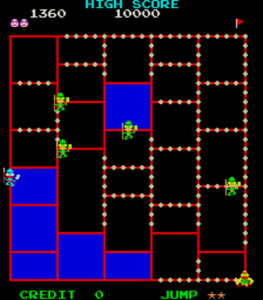

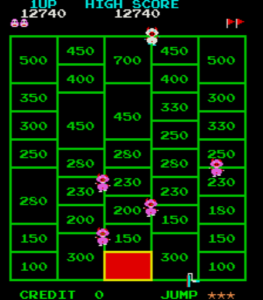

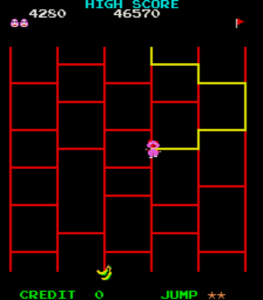

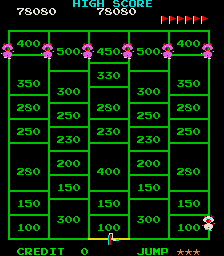

Christ Moyse at Destructoid tells us that Taito’s classic The New Zealand Story is coming to the Arcade Archives series. Gandalf could not be reached at press time for comment.

Two listicles:

Zoey Handley at Destructoid on the 10 best NES soundtracks. The list is Bucky O’Hare, Kirby’s Adventure, Castlevania 3 (Japanese version), Contra, Dr. Mario, Super Mario Bros. 2, Mega Man 2, Castlevania II, Journey to Silius, and… Silver Surfer?

Gavin Lane and the NintendoLife staff on the 50 best SNES games. The list is compiled algorithmically from reader scores, and can change even after publication. At this time, the top ten are, starting from $10: Donkey Kong Country 2, Earthbound, Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles IV, Super Mario RPG, Yoshi’s Island, Final Fantasy III, Super Metroid, Chrono Trigger, Zelda: A Link to the Past and Super Mario World on top.

Tom Phillips at EuroGamer mentions that the original developers of Goldeneye 007, recently rereleased after 25 years on Switch and Xbox platforms, were a bit miffed that they weren’t asked to participate in the festivities. At the time most of its developers were completely new to the game industry, and they’ve been generally snubbed by its publishers in talking about the new versions. Does feel pretty shabby, Nintendo and Microsoft!

Andrew Liezewski at Gizmodo talks about the graphics in an upcoming Mario 64 hack made by Kaze Emanuar. I’ve followed Kaze’s hacking videos quite a bit (I think one’s been posted on Set Side B before), and the optimizations they’ve made to Mario 64’s engine are amazing, not only eliminating lag but great increasing its frame rate and making it look better to boot.

And, at Kotaku, Isaiah Colbert reports on various things being done to celebrate Final Fantasy VII’s 26th birthday, including official recognition in Japan of “Final Fantasy VII day” and a crossover with Power Wash Simulator. Maybe they can do something about cleaning out all the grunge from Midgar, that city could use a bath.